What's Taking Russia So Long In The Donbass?

Less than four months into the Ukraine war, the cutting edge of Russia's sword is looking not just bloodied, but battered and blunted.

On the key front in the Donbass, Russian firepower dominates the battlefield, obliterating Ukrainian villages, towns, cities and defenses, while blasting holes in the morale of outgunned defenders.

But this grinding big-gun assault is not being followed up by fast-moving boots or tracks on the ground. As such, it is failing to win major victories, as key communications lines and hubs continue to hold – despite the extraordinary vulnerabilities facing the Ukrainian battlefront.

Increasing numbers of videos and reports of Ukrainian militia units refusing to advance or questioning their orders are emerging. But it is clear that Ukrainian forces have – thus far – fought both hard and successfully, though this assessment could change in a matter of hours.

It is possible that a sudden Russian offensive – which would only need to advance a handful of miles – could still cut off the defenders of the two key cities of Severodonetsk and Lyschansk. A wider attack mounted further west could trap all Ukrainian troops in the Donbass in a cauldron, or“kessel.”

The risks of Russia launching a coordinated, serial offensive must be straining the nerves of the Ukrainian high command – already stretched taut by the fighting in Severodonetsk. The massive bleed in men and materiel that a successful Russia“sickle cut” to their rear would generate would have catastrophic implications for the defense of the rest of the country.

This is especially the risk in the south, where Moscow has declared its intent to seize the entire Black Sea coastline. Exacerbating this risk is Ukraine's lack of a mobile mass of maneuver to counterattack if disaster looms.

Yet the apparent inability of the Russians, who have massed the bulk of their in-theater forces in the Donbass, to undertake a strategic mobile operation speaks volumes.

In fact, their offensive so far has been the opposite: Piecemeal attacks at the tactical level that seize small settlements but fail to destroy or capture large bodies of troops. Signals from the home front, meanwhile, are not encouraging.

The reactivation of outdated, 1961-era tanks back up independent analyses of massive Russian armored losses. Meanwhile, recent frustrated public commentary by two of the Kremlin's foremost warriors suggest that the campaign is failing to meet political aspirations.

A grim-faced President Zelensky (left) receives a military briefing. Photo: President of Ukraine Battle for Donbass

“The battle for Donbass will remind you of the Second World War, with its large operations, maneuvers, involvement of thousands of tanks, armored vehicles, planes, artillery,” Ukrainian Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba said at the tail end of a NATO foreign ministers' meeting in April.

Kuleba was speaking as Russian forces lifted their siege of Kiev and retreated. The battle for Donbass – where Ukrainians had been battling Russia-backed separatists since 2014 – became the hinge of fate.

Kuleba was not alone in his prediction: It was echoed by pundits and amplified by media. Three factors argued in favor of Russian forces seizing a decisive victory there.

One: With the spring thaw over, firming up the ground, Moscow's armored forces could at last deploy off-road, enabling the broad-front offensives its forces won fame for in World War II, which its large-scale exercises replicate to this day.

Two: The cone-shaped Ukrainian salient in the Donbass was acutely vulnerable to being cut off at its widest point, in the west, by a pincer operation from north and south – or either north or south.

Three: Russian President Vladimir Putin had set“demilitarization” as one of two key aims of his“special military operation.” With the bulk of the Ukrainian Army's heavy units fighting in the Donbass, a key operational objective lay within reach.

None of this, however, came to pass.

“Russia began the so-called battle for the Donbas with big plans: an offensive from the north, from Kharkiv, and from the south, near Zaporizhzhia, meeting in the city of Dnipro,” Ukrainian military analyst Mykhailo Samus told independent Russian media Meduza. “ The second arrows were drawn from Izyum in the north and Huliaipole in the south, meeting in Kramatorsk or Sloviansk.”

These attacks never broke into full offensive mode, thanks to determined Ukrainian resistance on the“shoulders” of the salient. As a result, the Russians were forced to adopt the opposite strategy: gnawing away at the Ukrainians around the periphery of the salient, but not closing it anywhere.

Meanwhile, their artillery-heavy advances have been destroying the urban assets they aim to capture. And Ukraine is not being“demilitarized.” Though it is doubtless suffering losses from artillery, units are not being annihilated.

In their one clear victory, Mariupol, Russian attackers trapped the defenders by pushing them back to the sea. But in Donbass, Ukraine's rear has not been blocked. This means units pushed out of positions have retreated westward, fighting an echeloned defense.

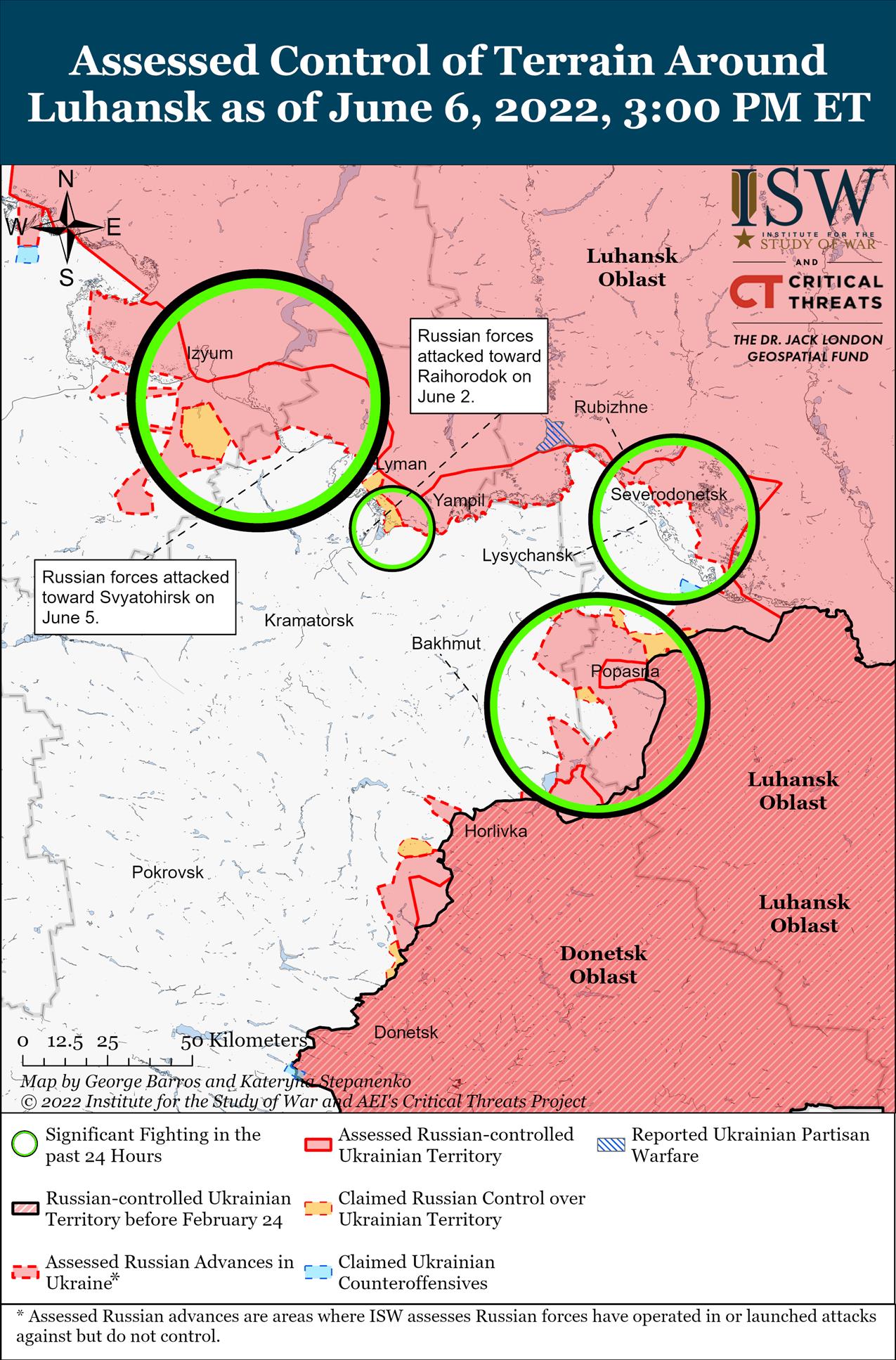

Situation map showing the perilous positions of Ukrainian troops in the Donbass salient (in white), surrounded on three sides by Russian/Russian-backed forces (in pink). Image: Institute for the Study of War Stubborn defenders

The Russian-speaking, coal-steel region of Donbass comprises two oblasts: Luhansk and Donetsk.

The twin cities of Severodonetsk and Lyschansk, on opposite banks of the Siversky Donetz River, are the last Ukrainian holdouts in Luhansk. As they occupy the last 5% of the oblast, they are politically important. Ukraine currently holds less than half of Donetsk.

Severodonetsk is surrounded on three sides with the river to its back. Seesaw street fighting has been ongoing for over a week.

Remarkably, Russian forces have not cut Severodonetsk off from its links to Lysychansk with precision artillery, drone or air strikes. That would trap the defenders, a reinforced brigade of mechanized infantry, as well as regional militia troops while preventing reinforcements and supplies from entering.

A Ukrainian TV team, embedded with one of Kiev's“foreign legion” detachments in an armored personnel carrier, crossed the bridge into Severodonetsk this weekend without coming under fire.

Still, Ukraine's governor of Luhansk, Serhiy Gaidai said on Monday the situation in Severodonetsk had worsened again after the defenders had pushed back the Russians over the weekend. According to some reports, and apparently following the example of Mariupol's defenders, they have retreated into the highly defensible Atoz Industrial Works.

But even if Russian troops take Severodonetsk, as seems likely, the battle looks set to continue in Lysychansk, which has the benefit of standing on high ground, a factor which favors defensive artillery spotting. (Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky personally visited Lysychank on June 6.)

And if Lysychansk falls? Unless Russian forces can cut off the road net to its rear by taking the town of Bakhmut, or with a much more ambitious pincer operation to take the cities of Kramatorsk and/or Sloviansk, which bestride the region's key north-south highway, there is plenty of ground for the Ukrainians to continue their fighting retreat.

It is a baffling situation for military experts. Looked at from the map table, all metrics favor the Russians: Weight of firepower, concentration of force and initiative. Ten days ago, a general level officer told Asia Times,“It is just a matter of time,” for Severodonetsk to fall.

He also predicted that a domino-style collapse of the front if and when that happens. So far, it has not.

Unless Russian generals' aim is brilliantly Machiavellian – to lure as many Ukrainian forces into the eastern end of the salient before snapping shut the trap – their forces are looking seriously challenged.

Failure of the tank armChallenges are clear on both the manpower and mobility fronts.

The Kremlin is fighting its war with a limited pool of professional troops rather than its full army. Moreover, it appears to be suffering from a weakness in infantry . The most casualty-intensive form of combat is urban warfare, and this is how the Ukrainians have dictated the fighting – in the suburbs around Kiev and Kharkiv, in Mariupol, in Popasna and now in Severodonetsk.

Smart generals wielding competent maneuver forces can obviate urban combat by bypassing and cutting-off points of resistance like towns and cities. And NATO has long believed that Russia possessed a dangerously powerful armored force.

Russian tanks rolling through the Donbass in a file photo. Image: Tass

But, compounding its infantry shortfall, Russia's maneuver force has been seriously attrited – largely due to its misemployment in road-bound columns in the early phase of the war.

Specialist website Oryx, which calculates AFV losses only with photo or video identification, finds that Russia has so far lost 4,246 armored fighting vehicles, or AFVs, including 761 tanks. And that number is conservative.

“This list only includes destroyed vehicles and equipment of which photo or videographic evidence is available,” Oryx, which includes a photo of clip of each vehicle in its database, notes.“Therefore, the amount of equipment destroyed is significantly higher than recorded here.”

The lost tanks include hundreds of the aging T-72 and scores of the more up-to-date T-80. Russia's most modern tank, which has been spotted on military parades, is the T-14 Armata. However, that is not believed to be ready for deployment as it is still undergoing trials.

An accurate tally of AFV losses – which include personnel carriers and mobile artillery as well as tanks – will not be feasible until hostilities have ceased. But the seriousness of attrition is clear from the Kremlin's decision to deploy from mothballs a tank with a design dating back to 1961.

Austrian Colonel Markus Reisner, delivering a YouTube briefing last week , noted that train loads of T-62 tanks are arriving in the theater. While commenting on their antiquity, he noted that“The Russians use it more or less as an assault gun.”

If accurate, that is a telling analysis.“Assault guns” are armored artillery pieces mounted on tank chassis to provide infantry with direct fire support. As they move at the plodding pace of the foot soldier, they do not need high-speed tank engines nor the advanced optics that make tank fire so effective at long range.

Footage from Mariupol, as well as the damage its buildings have sustained, show that in the street fighting Russian tanks were used as assault guns. Footage from Donbass shows Russian tank formations in static, hull-down positions operating as direct-fire artillery.

These deployments are not the optimal tactical usage of tanks. Nor are they likely to change Russia's game or accelerate its advances.

Moreover, in street combat, Russia's awesome weight of indirect artillery fire – i.e. shells and rockets fired in a parabola rather than in a straight line – and airpower is significantly invalidated.

Tanks are“mailed fists” – designed to punch through enemy lines, then conduct fast-moving mobile operations in the enemy's rear. Once an enemy force is dislocated, his front can be rolled up, and his formations can be encircled and destroyed.

Such operations are at a particular premium in a landscape as vast as Ukraine's.

Indeed, many experts believe history's largest armored clash took place outside Kiev in 1941. (Others argue for the battle of Kursk – where a German attacking force failed to crush a vast Russian salient – near Belgorod in 1943.)

These factors, combined with the Russian Army's traditional focus on artillery, explain the current nature of the fighting.

Frustration in MoscowSigns are appearing that not all is well in the Kremlin.

The ever-bullish leader of Russia's Republic of Chechnya, Ramzan Kadyrov, said on Telegram following a meeting with Russian Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu last Thursday that Russian operations are to be accelerated.

Russian President Vladimir Putin, Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu and other senior defense officials. Photo: AFP / Alexey Druzhinin / Sputnik

Shoigu has“set new goals that aim at improving further tactics,” Kadyrov said in social media post reported by Ukrainian media Pravda.“The measures taken will increase manyfold the effectiveness of offensive maneuvers that will contribute to increasing the pace of the special operation.”

Kadyrov, a fierce Putin loyalist, has sent irregular Chechen units comprising military police, light infantry and special forces to the war. They have been prominent fighters in urban areas, notably Mariupol and now Severedonetsk.

However, there has been no indication, as yet, of a change in tactics or an acceleration of advance since the Kadyrov—Shoigu confab, which took place on the 100th day of the war.

Some Russian figures are reportedly digging in for the long haul.“We'll grind them [the Ukrainians] down in the end,” a source with links to the Kremlin reportedly told the Meduza outlet .“The whole thing will probably be over by the fall.”

However, the source conceded that that outcome could depend upon Russian deploying conscripts alongside its professionals – a major and possibly risky next step for the Kremlin.

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the

information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept

any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images,

videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information

contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright

issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Comments

No comment