Perfect Storm Of Turbulence For Indebted Little Laos

The Lao People's Revolutionary Party (LPRP), the country's ruling communist party, has had a rough and tumble past three years.

Laos had an especially bad pandemic, while the economy barely grew in 2020 and 2021. Only Brunei, Thailand and the Philippines have a higher ratio of deaths per population from Covid-19 in Southeast Asia, according to Our World In Data.

Only 67% of the Lao people have had at least one vaccine. The Nikkei Covid-19 Recovery Index ranked Laos as the worst performer among more than 120 countries.

The year 2022 was supposed to be the year of recovery. But the war in Ukraine, which has sent international fuel prices skyrocketing, has hit Laos particularly hard. In April, petrol and diesel prices rose 72% and 96.6% year on year respectively, according to the Lao Statistics Bureau.

For months, people have had to queue for hours at petrol stations across the country due to fuel shortages. Since May 9, those shortages have also hit Vientiane, the capital and home to most of the nation's political and business elites.

Angry posts now appear regularly on social media. The government says little about how it intends to sort it out, adding to public frustration. Petrol station owners have also come in for criticism for allegedly exploiting the situation.

In a rare comment, on May 22 the Ministry of Industry and Commerce and the Lao Fuel and Gas Association appealed to the public to only buy what petrol they need in a bid to save dwindling fuel reserves for farmers and transport workers.

The LPRP, in power in the one-party state since 1975, can blame this on issues outside its control. But it has fewer excuses elsewhere. Inflation has soared since the beginning of the year, from 6.25% year on year in January to 7.3% in February and 8.5% in March. The latest estimate by the Lao Statistics Bureau is that it reached 9.9% in April.

A second, and corollary crisis, is with exchange rates. This time last year the Lao kip was trading at about 9,430 per US dollar. As of May 24 this year, it was at 13,271, a 40% depreciation.

Exchange rates for the Lao kip and inflation have made small things like a cup of coffee much more expensive for locals. Photo: Facebook

“The Lao kip is under pressure. In September 2021, something seemed to snap in the Lao currency and it's been depreciating quite rapidly since then,” said Keith Barney, associate professor at the Australian National University.

Demand for foreign currencies needed for imported goods is growing. At the same time, the state is desperately in need of foreign currency for debt service repayments. The central bank blames informal currency traders for hoarding money. Experts say it's more complicated.

Sonexay Sithphaxay, governor of the Bank of the Lao PDR, the central bank, admitted in a press conference this month that only 33% of the country's export value actually re-entered the economy through the banking system over the first four months of this year. The rest is being stored offshore, he said.

For years, pundits have been warning about structural problems. Laos never really“opened up” to the world in the late 1980s. Trade with the West, or even with Asian giants like Japan and South Korea, is minimal.

Economic diversification has also been laggard: Laos mainly sells minerals, food and hydropower and trades almost exclusively with neighboring Thailand, Vietnam and China.

While gross domestic product (GDP) growth slipped from 8% in 2013 to 6.3% in 2018, it fell sharply to 4.7% in 2019, a sign that things were already heading in the wrong direction before Covid-19 hit.

Instead of building a sustainable manufacturing base, the government has focused on high-cost, debt-driven projects. Hundreds of hydropower dams are running or under construction. Most significantly, the government has taken a US$6 billion gamble on a railway connecting Vientiane to Kunming, in southern China, that opened late last year.

The line aims to turn Laos from land-locked to“land-linked,” the government says.

But it's a high-risk venture with loans outstanding to China and the Lao state will incur most costs if the line fails commercially. Much depends on whether other Southeast Asian governments, namely Thailand, decide to extend a cargo railway route all the way through the region.

A promotional poster for the 414-kilometer Laos-China railway project that promised to transform Laos from landlocked to land-linked. Photo: Facebook

Laos' communist government has laden the state with debt – and, some think, too much to China, which some have accused of pushing“debt-trap diplomacy” on its southern neighbor.

Last August, the World Bank stated in a report that Laos' public debt stood at $13.3 billion, or 72% of GDP. It could be much higher, though. Bounchom Oubonpaseuth, Laos' finance minister, says the country has to pay more than $400 million a year in interest alone. It almost missed those payments last year.

International rating agencies have downgraded Laos' credit score, making it harder to raise money on international bond markets – something Vientiane has been trying to do recently as other debts come due.

Laos had the chance to sign up for the World Bank's Debt Service Suspension Initiative but decided instead to go down the path of direct debt restructuring arrangements with China, its largest creditor. That saw Electricité du Laos, the state-run power company, partially sold off to a Chinese firm.

For the most part, though, these deep-rooted problems aren't so obvious to much of the public. Debt is complicated and the state-owned media has no incentive to explain it to readers. Large-scale investment in megaprojects has injected capital into rural areas. The state sector is still a major employer.

But crippling inflation and fuel shortages are obvious examples that something is amiss in the economy's management. Public anger is mounting. There are also murmurs of displeasure as the government hastily reopens the country, in a bid to gain some much-needed tourism revenue.

There has been chatter on social media about starting street protests, although none have materialized so far.

Public shows of dissent are rare in Laos. Underground democracy movements have planned street protests in the past but most lasted only a few minutes before the police struck. Most activists are either in jail or have lived for years in exile.

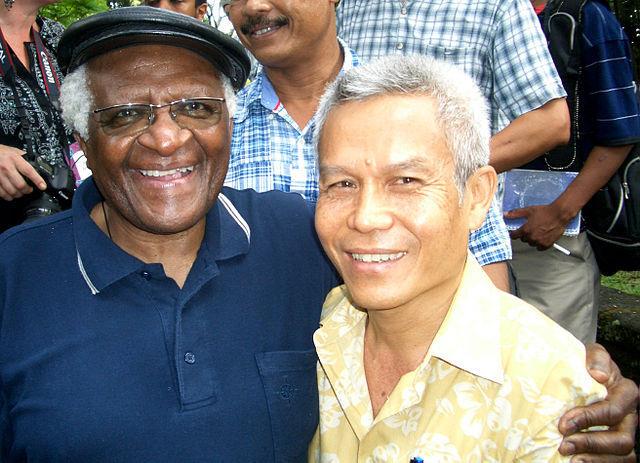

Others, like community development worker Sombath Somphone, who was abducted in Vientiane in 2012 and is still missing, have apparently been disappeared by the state.

Lao activist and community development worker Sombath Somphone, pictured here (R) with Nobel Peace Prize winner Desmond Tutu, was abducted on the streets of Vientiane in 2012 and has not been heard from since. Image: Supplied

Unlike in Vietnam, civil society activism in Laos is comparably nonexistent; there's no recognizable pro-democracy movement. Nonetheless, the educated youth are pro-West and want to develop and move toward democracy, said one observer of Lao politics who requested anonymity for reasons of personal security.

“They are openly criticizing the government and calling for a change of leadership,” the source added, referring to the displeasure from gas shortages and inflation.

Still, the ruling communist party's downfall is very unlikely. It controls every institution in the country, as well as most of civil society. About 5% of the population are party members, it was announced at the LPRP's National Congress in January 2021.

That was an increase of nearly 80,000 people since the 2016 congress, though a much higher percentage of Laos are members of the party's organs, such as the Lao Federation of Trade Unions, Lao Women's Union and Lao People's Revolutionary Youth Union.

At the 2021 congress, it was decided that social media needed to be more tightly regulated. The previous year, the“if Lao politics was good” hashtag was trending amongst Laos in Thailand.

Neither is there a realistic alternative to the LPRP. A royalist government-in-waiting sits abroad but exiled and foreign-born Laos spend much of their time squabbling amongst themselves.

Whereas the US Congress and the European Parliament enjoy debating how best to condemn repression committed by Vietnam's communist bosses, they almost never find time to talk about Laos. Even if they did, Western democracies hold zero political sway in Vientiane.

More probable, one analyst said, is a rupture from within the LPRP. Although rarely as factious as its Vietnamese counterpart, divisions have emerged in recent years. Some apparatchiks advocate for a westward pivot in a bid to increase trade with the US and EU.

To do so, the government needs to engage in more political and economic liberalization, they argue. Lao business groups are now trying to kickstart cooperation with South Korea, a US ally.

Bounnhang Vorachit, the former party chief, warned at last year's congress that the LPRP could become obsolete if it fails to reform. Such talk is common from departing grandees, but the congress did see a generational handover from wartime soldiers and apparatchiks to a new breed of technocrats and career cadres.

Phankham Viphavanh, a former president of the Lao-Vietnam Friendship Association, has seemingly worked to balance Laos' relations between Vietnam and China since he became prime minister last year. That did not sit well with the LPRP's hardline pro-Beijing factions, however.

He also likely instigated a cabinet reshuffle in February to gain more control over economic matters. Khamjane Vongphosy, formerly head of the Prime Minister's Office, became the new Minister of Planning and Investment.

Laos Phankham Viphavanh is struggling to keep a grip on the economy and manage intra-party rivalry. Image: Global Times

If so, the prime minister will likely face more flak for the current economic crisis. That could give more ammo to his opponents.

Meanwhile, the scions of two political dynasties, the Siphandones and Phomvihanes, also appear to be duking it out. Sonexay Siphandone, the son of Khamtai Siphandone, the LPRP chairman from 1992 until 2006, was removed as Minister of Planning and Investment in February.

Some thought he would have become prime minister last year, though he still remains deputy prime minister. His brother, Viengthong Siphandone, is president of the People's Supreme Court.

Can the party turn things around? Probably not in the short term, analysts reckon. The fuel crisis and galloping inflation will inevitably continue throughout the year. The former is dependent on events far removed from the LRPR, such as the Ukraine war and international markets.

Economic softening this year in China, Laos' main trading partner, will further hamper recovery efforts.

Usually, the LPRP makes Panglossian projections. But Prime Minister Phankham attempted to temper expectations last year when he announced rather unspectacular economic growth forecasts.

He reckons the Lao economy will grow by only 4% annually until 2025. The World Bank, rarely the optimist, is projecting 3.8% for this year.

As such, austerity is now the buzzword in Vientiane. The government wants to limit state spending and raise taxes, sensible policies that the World Bank also advises. Yet the government has been trying to do both for years with little success.

Even if successful, it will put additional burdens on the public, raising further problems for the LPRP.

Phankham, then, is likely to be remembered as a crisis prime minister, drifting from one problem to the next. For those who want change in Laos, the best hope is that the current economic predicaments result in greater debate within the LPRP.

That could pressure grandees to listen more attentively to reformist-minded politicians. It might also see a rise in populism, with factions of the party vowing liberalization alongside bread-and-butter policies.

Follow David Hutt on Twitter at @davidhuttjourno

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the

information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept

any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images,

videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information

contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright

issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Comments

No comment