When The Air In Kashmir Turned Dark

I have spent years speaking about waste, water, mining and the slow poisoning of our rivers. But I never thought I would wake up one day and worry more about the air in Kashmir.

I live with the idea that our land is under stress, though the numbers I saw this past week forced me to sit down and breathe a little slower.

A friend from Budgam called me with data that felt unreal: the Air Quality Index touched 426 near the DC office on a cold Saturday morning.

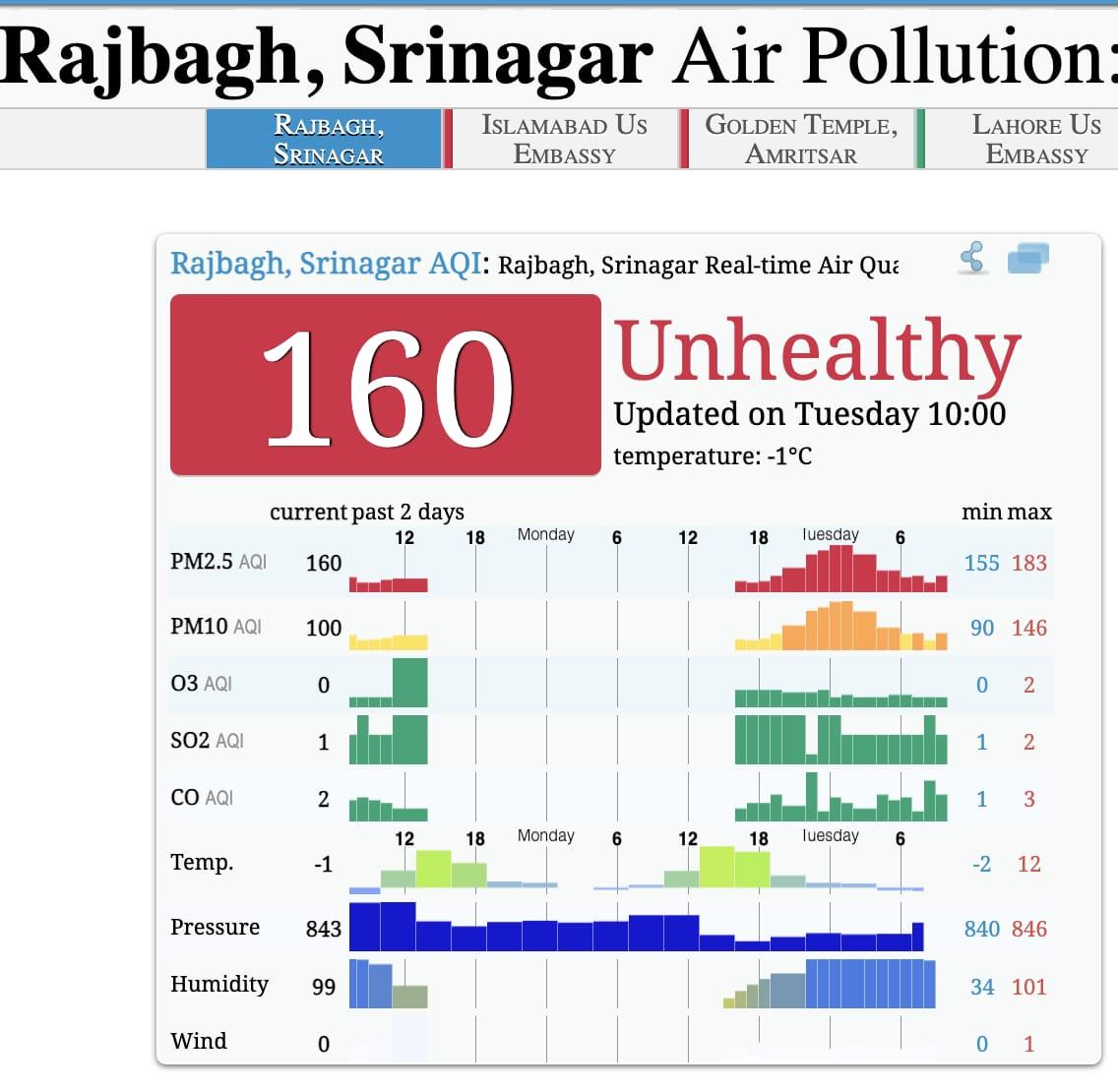

ADVERTISEMENTAnother message told me that Khawaja Bagh in Baramulla touched 450 the next day. Srinagar had been hovering between 160 and 175.

This is our home, a place people discuss as a valley of clean winds and open sky, and the monitors now say we are breathing hazardous air.

I kept thinking of the Supreme Court order from August 2025.

For the first time, every Pollution Control Board in the country, and Pollution Control Committees in Union Territories, can impose environmental compensation on polluting bodies.

The apex court made it clear that they can seek fixed sums or bank guarantees when there is actual damage or a clear threat of it.

I had welcomed this order with hope. It meant people would not have to run to High Courts or the NGT each time a river turned brown or a landfill caught fire. They could walk into a pollution control office and file a complaint.

That power is now in the hands of the Jammu and Kashmir Pollution Control Committee.

I keep asking myself if we are using it with the urgency this moment demands.

A few weeks ago, a small team from the J&K RTI Movement and the J&K Climate Action Group met the JKPCC Chairperson, Vasu Yadav, in Srinagar.

We spoke at length about illegal riverbed mining in Doodh Ganga, sand and clay excavation across our karewas, and the ongoing destruction around Newa in Pulwama. We raised the worrying practice of burying and burning municipal waste. The smoke from these dumps alone can fill entire neighbourhoods with toxins.

At the time, I had not started tracking air pollution in Kashmir. Once the numbers began showing up on my screen, I realised how much we had missed in that meeting.

Anyone with a phone can now check daily AQI levels. Anyone with a modest sensor can measure air quality outside their own home.

Many residents have started doing this. It is not a good sign when citizens feel they must monitor what the state should.

Sadly, in many Kashmir districts, like Budgam, Pulwama, Baramulla and Anantnag, clay and sand are being ripped out of the land at a pace that fills the air with dust.

Newa, Brarigund, Kultreh, Brinjan, Nowhar, Buzgoo, Nagam, Tangnad and Pallar are only some of the places struggling with this.

The dust sticks to windows, rooftops and lungs. It is the same story in Pattan and in parts of Bijbehara.

Autumn brings its own wave of smoke as people burn dry leaves in heaps. Every bit of it settles into the air we breathe.

The chairperson told us that action has begun in some cases. Environmental compensation is being worked out for illegal waste dumping in Newa and for the mining in Doodh Ganga.

In the Shali Ganga case, where the Supreme Court upheld the NGT ban on mining by NKC Projects, the committee is taking steps to follow the court's directions on compensation.

These are encouraging signals, though we need more than signals now.

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the

information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept

any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images,

videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information

contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright

issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Comments

No comment