The UK Must Secure Supplies Of 34 Critical Minerals Says New Report Here's How

We are in the midst of a geopolitically charged race for lithium and other so-called critical minerals. These materials are crucial for renewable energy, transport, data centres, aerospace and defence, among other things, and the transition to net zero will place unprecedented pressure on their supplies.

Accordingly, the UK has just published a new Critical Minerals Strategy, identifying 34 of these raw materials as essential for national security and the economy. Meeting demand for them will be a monumental challenge.

Take copper: even though it is a well-established commodity, in the coming decades the world will need more of it than has ever been mined in human history. Yet opening a new mine takes a decade and costs billions.

Other minerals, such as cobalt or the 17“rare earth elements”, present a different problem: supplies are concentrated in countries with competing strategic interests or developing nations, and can be hard to access.

For instance, most high-performance magnets – including those in wind turbines – use the rare earth neodymium, and the vast majority currently comes from China. The metal cobalt is used in batteries: about half of the world's reserves are in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

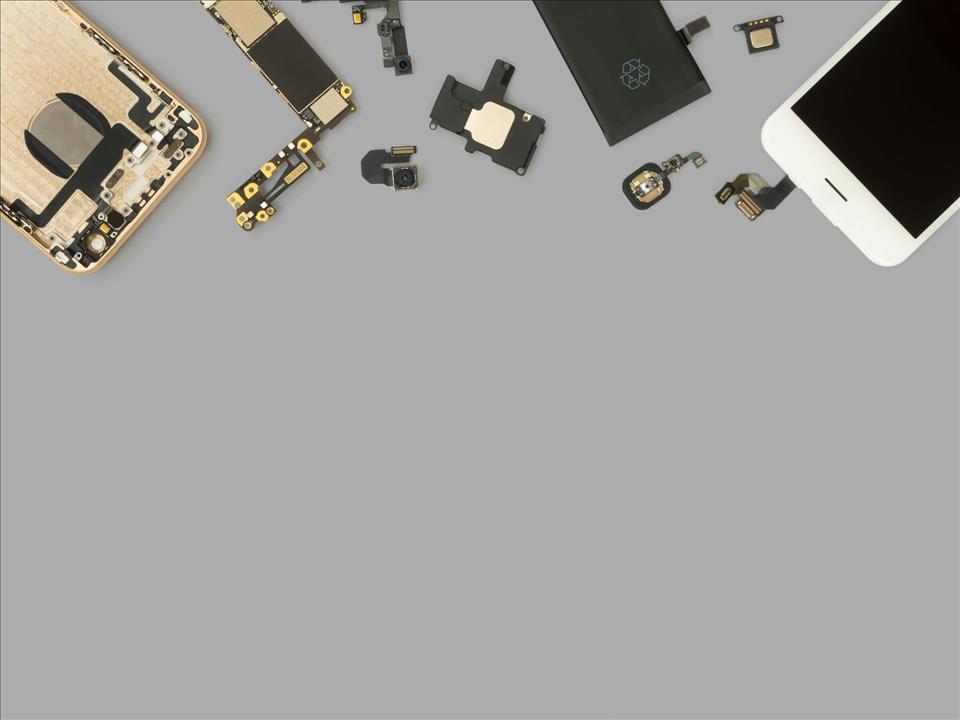

The many different minerals required for electric vehicle batteries. Dimitrios Karamitros / Shutterstock (data: Transport & Environment)

Historically, mining has caused significant social and environmental harm in host countries – frequently developing nations – while delivering most of the benefits to consumers in wealthier countries.

Wealthier countries could just turn a blind eye to those harms, but there is a growing awareness of the impact of mining. This, combined with the concentration of supplies in certain countries, creates a challenge for places like the UK, which don't have critical mineral resources.

Disruptive technologiesNew extraction technologies are emerging in the UK and elsewhere. While some companies are making progress with“green mining” – using electric vehicles and renewable energy – the most promising solutions are more radical.

One new avenue is recovering geothermal energy alongside critical minerals. The hot fluids beneath ancient volcanoes can be rich in lithium, gold, silver and other critical elements, with each volcanic system offering its own distinct mix of resources.

Tapping into this heat can offer a double benefit: clean energy and useful minerals. In Cornwall, south-west England, there are plans to do this at a reopened lithium mine.

Synthetic biology is another exciting development. This involves scientists modifying microbe DNA to selectively scavenge specific elements from their surroundings, such as battery waste and sewage sludge. These micro-organisms could recover resources even in extreme environments.

Read more: As mining returns to Cornwall, lithium ambitions tussle with local heritage

Circular resourcesMaking better use of the resources we already have is essential. This goes beyond traditional recycling to develop new ways to turn by-products and discarded materials into valuable resources, while simultaneously cleaning up legacy pollution.

For example, mining tailings and coal fly ash contain recoverable metals, and innovative“smart” minerals and microbes can be harnessed to extract them.

However, recycling alone won't meet future demand. Many metals, while highly recyclable, remain in use for decades before re-entering the supply chain. Take nickel, for instance. It's an important battery metal, but can stay in circulation for 30 years or more, limiting its availability in the short term.

Many minerals crucial for phones or batteries come from artisanal mines in DR Congo. Erberto Zani / Alamy Mining that does not curse the locals

Future mining must avoid the“resource curse” – the paradox where resource-rich countries often fail to benefit fully from their own mineral wealth. Principles for a new approach should include investment in local industries in producer countries so they can make batteries and magnets, not just export ore.

They should also require genuine community engagement, giving mining de facto permission and acceptance from locals. This unwritten set of positive (or at least tolerant) attitudes is sometimes termed the“social licence” to operate – and without it, mining operations can fail.

Mining companies should promote best practices with regard to the environment, health and safety, and workers rights. Regulators need to enforce environmental protection with teeth, including rewilding and ecosystem restoration after a mine has been emptied.

The mining industry has a bad reputation for a reason, with a history of high-profile environmental disasters. The growing emphasis on environmental, social and governance criteria for investors is encouraging, and may help deliver change.

The UK government's new strategy outlines promising goals on domestic development, the circular economy and supply chain resilience – but its measures of success don't match the ambition. Its support for innovation is also cautious and focuses on established approaches. What's needed is an entirely new way of thinking about how to secure these resources.

This means recovering materials from new sources, using them more wisely, ensuring mining communities benefit, and cleaning up environmental damage. It also means building resilient supply chains that can withstand a major change of government, an economic crash, or some other geopolitical shock.

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the

information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept

any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images,

videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information

contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright

issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Comments

No comment