CEE Countries Face A Race Against Time As RRF Deadline Approaches

Source: EC, Eurostat, Macrobond, ING

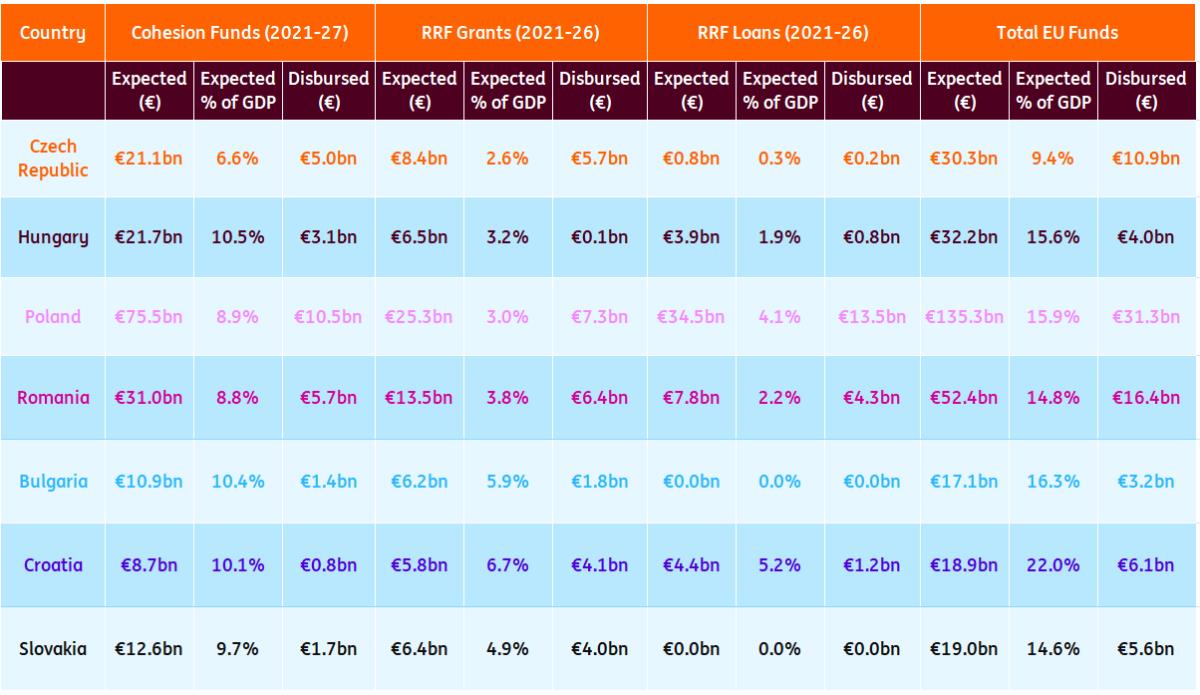

The Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) region has seen plenty of changes in regard to the European Union (EU) funds situation since our previous update in late 2023. On the political front, Poland's government has unlocked funds since coming to power, while Romania has also seen movement after forming a new coalition and passing some fiscal reforms. In Hungary, progress has been limited with a large chunk of EU funds frozen amid rule-of-law disputes, which will likely be a hot topic for next year's elections.

But the region, in general, is still lagging behind the EU average in terms of absorption, and time is running out to use all available resources. Under the current framework, Member States have until 31 August 2026 to complete all milestones and targets, and the European Commission (EC) has until 31 December 2026 to make all payments for the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF). Poland's minister for EU funds indicated in June that the EC agreed to extend the deadline for RRF grants for Poland through to the end of December 2026, although there is little clarity on whether this will apply to other countries. Regular structural payments under the Cohesion Policy Framework can generally be disbursed until the end of 2029 under the T+2 rule (for the 2021-2027 budget cycle).

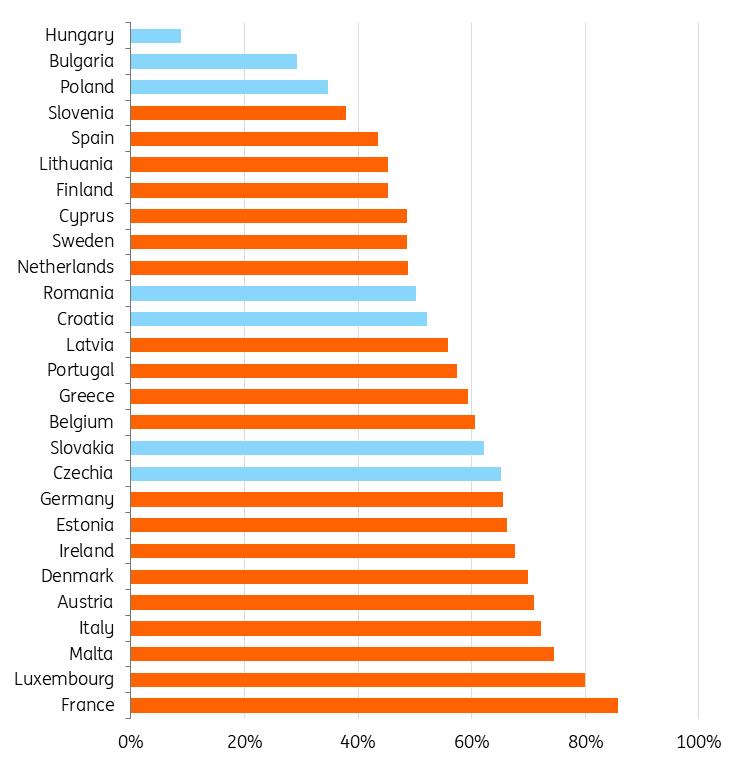

RRF deadline puts pressure on absorption ratesWith the 2026 deadline for RRF payments looming, the absorption rate so far has been mixed for CEE sovereigns. Across grants and loans, Hungary is the biggest laggard, with just €920mn in RRF funding disbursed, representing 9% of the planned allocation. Bulgaria has also been slow, with a 29% absorption rate, although the country received approval for its modified RRP this summer, before receiving part of its second tranche (€439m) recently. Poland has been making progress, but is still among the worst performers within the EU (35% absorption, vs the EU average of 54%). Slovakia and the Czech Republic stack up better, above the EU average, albeit well below France's leading 86% in the EU.

RRF absorption rate (% of total)

Source: European Commission, ING SAFE provides additional financing for military spending

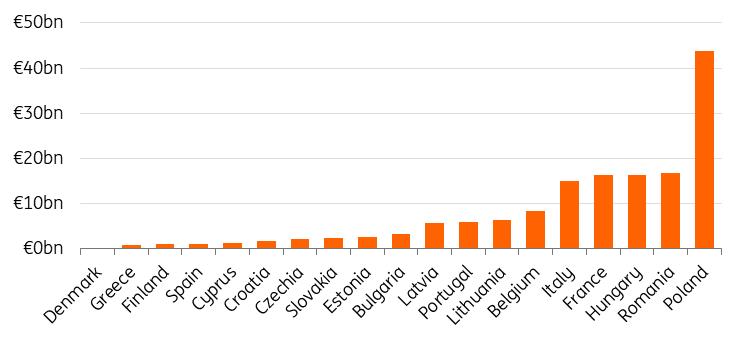

Given the focus on military spending as a pressure point for fiscal accounts, the Security Action for Europe (SAFE) instrument comes at an important time and offers some additional resources for CEE countries. The new instrument should provide an additional €150bn in loan funding, in the form of long-maturity loans with a maximum duration of 45 years and a 10-year grace period for principal repayments. The loans will be used for defence procurement, with no more than 35% of component costs originating from outside the EU, EEA-EFTA, or Ukraine.

Within the rough framework for country allocations, Poland, Romania and Hungary are set to be the top three beneficiaries – €43.7bn for Poland, €16.7bn for Romania and €16.2bn for Hungary. Submission of National Defence Investment Plans is expected by 30 November 2025, with pre-financing likely to start early next year.

Estimated SAFE funding by country

Source: European Commission, ING Country updates

Poland: Slow absorption of EU funds delays the expected investment rebound to 2026

The current government has successfully unlocked EU funds from both the RRF and Cohesion policy under the new EU financial perspective. However, nearly two years of implementation time have been lost. The judiciary super-milestones were crucial for unlocking payments in 2024, and any potential delays in implementing judiciary reforms under the new president, Karol Nawrocki, are not expected to impact disbursements from Brussels to Warsaw.

Progress in effectively disbursing these funds to final beneficiaries remains relatively slow. As of the end of 2024, Poland had transferred approximately PLN10bn from RRF grants to final beneficiaries. Of the remaining PLN100bn (approximately €23 billion, or 2.6% of Poland's GDP), it is anticipated that around 70% will be allocated to end users by 2026. Earlier this year, we expected a more even distribution of RRF payments between 2025 and 2026. This forecasts only a modest boost to investment this year, a trend corroborated by recent construction output data, while projecting a cumulation of RRF payments and robust investment stimulus in 2026.

The RRF implementation delays can be partly attributed to three revisions of the National Recovery Plan (NRP), two of which were introduced by the Tusk government. The most recent revision, made in mid-2025, reallocated approximately PLN26bn from RRF loans to a newly established domestic Security and Defence Fund. Also, the BGK development bank has concluded major subsidised RRF loan agreements with power companies and the electricity grid operator, totalling about PLN55bn. Nevertheless, in late August, the government decided to reduce the total RRF loan allocation of nearly PLN150bn by PLN22bn (€5.1bn). This highlights the significant challenges associated with Poland's compressed timeline for RRF implementation.

Poland – Capital accountRolling 12-months

Source: National bank of Poland, Macrobond, ING

Hungary: Politics complicates the EU funds outlook

Tensions between Hungary and the European Union remain high, with little prospect of a resolution to the complex issues in the near future. The frozen funds due to the rule-of-law issue continue to negatively impact the Hungarian economy. Real GDP growth has stagnated for three years. The outlook for growth remains unclear, primarily due to low consumer and business confidence and a lack of investment activity. If the frozen EU funds were released, the money could circulate back into the economy, raising domestic demand. This is why the upcoming parliamentary election is focusing increasingly on the issue of obtaining EU funds. The current government (Fidesz-KDNP) has repeatedly stated that if no progress is made in releasing the funds, Hungary will use any means necessary to push the EU into providing them. One method mentioned for doing so would be to exercise the right to veto the EU's upcoming financial plan. The challenger party, TISZA, has promised that if they are elected in spring 2026, one of their first measures will be to comply with EU rules and secure the funds. However, even if a political party manages to unfreeze the funds by 31 August 2026, project-specific funding requests must still be submitted by 30 September 2026.

That said, the EU's successful acceptance of the SAFE funding programme should be viewed as a positive development. Although Hungary did not support it, the country could be one of the programme's biggest beneficiaries. The Hungarian state requested €16.2bn, the third-highest amount after Poland and Romania. If the process is successful, Hungary could receive favourable loan funds as early as the first quarter of next year and use some of them to offset earlier defence spending. However, conflicting information exists regarding whether the SAFE funds will be available to Hungary without a resolution on the conditionality mechanism.

If the government fails to comply with the rule-of-law conditionality mechanism by the end of 2025, it will forfeit an additional €1bn from the Cohesion Fund envelope. If Hungary does not comply by the time the RRF deadline arrives, it will also need to repay the RRF advance payments (approximately €1bn). And, on top of all that, Hungary is still paying a daily penalty fee of €1m over its asylum policy, on top of the lump-sum penalty of €200m incurred in June 2024. The EU is deducting this fine from ongoing EU fund payments, thereby reducing the amount actually received.

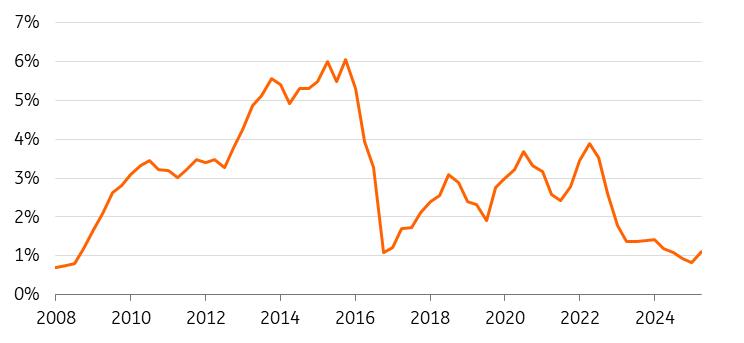

Hungary – EU transfersRolling 4Q, % of GDP

Source: National bank of Hungary, Macrobond, ING

Romania: Hopes for a record year of EU inflows

Romania remains one of the most reliant CEE countries on EU funds, with allocations under both the Cohesion Policy (2021–2027) and the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) forming a critical pillar of its investment and fiscal strategy. The country has made progress in recent months, but absorption rates and reform implementation continue to pose challenges as the August 2026 RRF deadline approaches.

As for the cohesion funds, Romania is allocated approximately EUR31bn under the 2021–2027 Cohesion Policy. By mid-2025, Romania had received around EUR5.3bn, representing a 17.0% absorption rate. The pace of contract signing and project calls has increased, with almost EUR32bn already allocated to various projects as of mid-2025 (though the actual spending and invoicing will come with a delay).

Romania's revised National Recovery and Resilience Plan (PNRR) now totals EUR21.4bn (EUR13.6bn in grants, EUR7.8bn in loans), down from EUR28.5bn initially, following negotiations with the European Commission to adjust for project delays and shifting priorities. The renegotiation process involved significant reallocations: for example, EUR2.17bn in infrastructure projects (notably segments of the A7 Moldova Motorway) were shifted from loans to grants, while some hospital and railway projects saw budget cuts or were moved to other funding streams. Some projects, such as segments of the A8 motorway, are now expected to be funded under the Cohesion Policy or the SAFE Programme instead. The third payment request under the RRF was only partially fulfilled (EUR1.3bn out of EUR2bn), with the remainder pending reforms around special pensions, corporate governance in state-owned enterprises, and making the Agency for Monitoring Public Enterprises operational.

Looking ahead to next year and with the RRF facility expiring in August 2026, the government faces pressure to accelerate reforms and project implementation, notably in infrastructure, healthcare, and digitalisation. That said, 2026 could theoretically be a record year in terms of EU funds inflows, with almost EUR11bn left from the renegotiated RRF, plus a lower but still significant amount from the Cohesion Funds (say around EUR4-5bn). However, persistent administrative inefficiencies, political uncertainty, and slow project execution continue to hinder full absorption of available funds. Therefore, the risk of partly losing some of the allocations remains real.

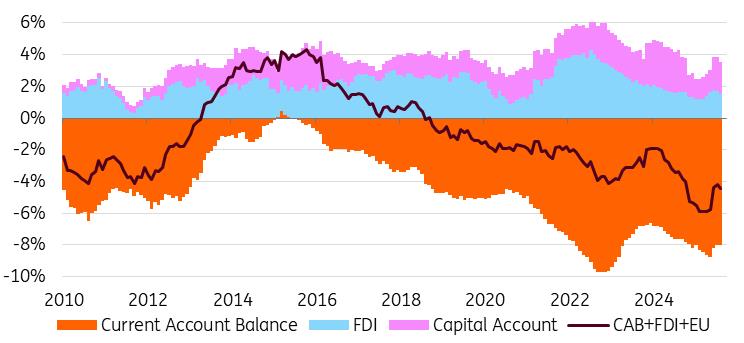

Romania – Basic balance% of GDP

Source: National bank of Romania, Macrobond, ING

Overall, the implications for CEE sovereigns are clear: Time is running out, so improving the absorption of EU funds heading into 2026 should be a clear priority. The good news, at least for Romania and Poland, is that EU fund inflows should accelerate in 2026, supporting public investment and also reducing the reliance on FX bonds for external funding.

Access to EU funds, particularly with the addition of the SAFE instrument, should therefore remain a key credit strength for EU members within the EM space. For Hungary, the picture is more uncertain, with the government recently revising its fiscal projections wider and planning more FX bond issuance next year, while also talking up the prospects for financial support from the US as an alternative to EU funds.

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the

information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept

any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images,

videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information

contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright

issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Comments

No comment