India's Shrimp Crisis: Can 'Atmanirbhar Prawns' Scale Trump's Tariff Wall?

Velankanni (TN)/Bhimavaram (AP): In 2018, when Venkatapathy Raju, a software engineer, chose to give up his promising job in the IT sector and join his father's shrimp business, things were looking good. Bhimavaram, his hometown in Andhra Pradesh, was fast becoming the nerve centre for shrimp farming. The land was virgin and water aplenty. A high shrimp survival rate of over 80% meant steady output, which was lapped up by exporters at good prices. Over the next seven years, Raju expanded the farm size from 100 to 650 acres.

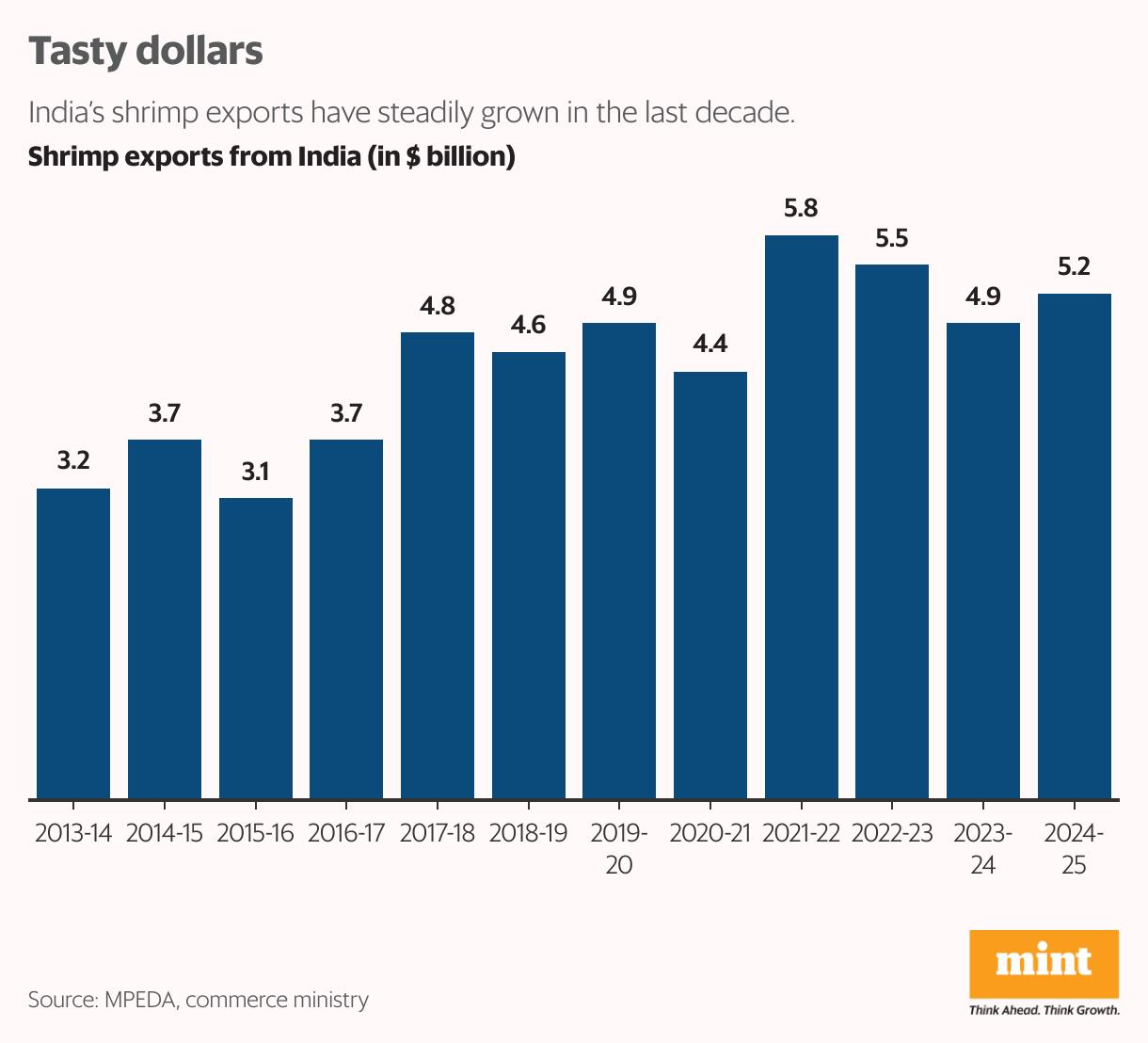

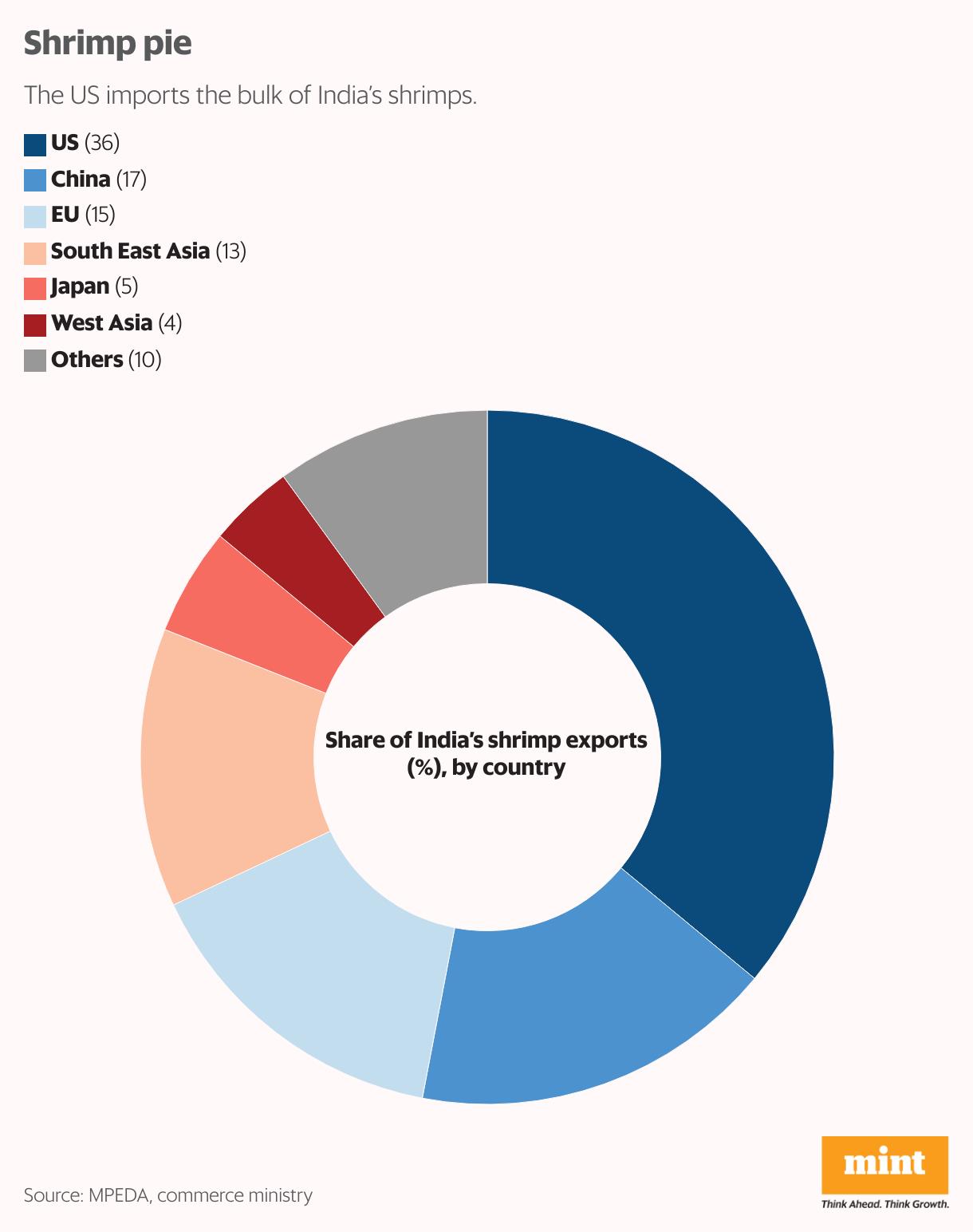

2025 turned out to be different. US President Donald Trump imposed 50% duty on Indian goods and that has hit shrimp exports hard. About 36% of Indian shrimp, and most of Bhimavaram's production, are exported to the US. Farm gate prices have since fallen by up to 20%.

Raju, nevertheless, hasn't given up.“My passion for farming shrimp has kept me from questioning the decision to leave IT," he said.

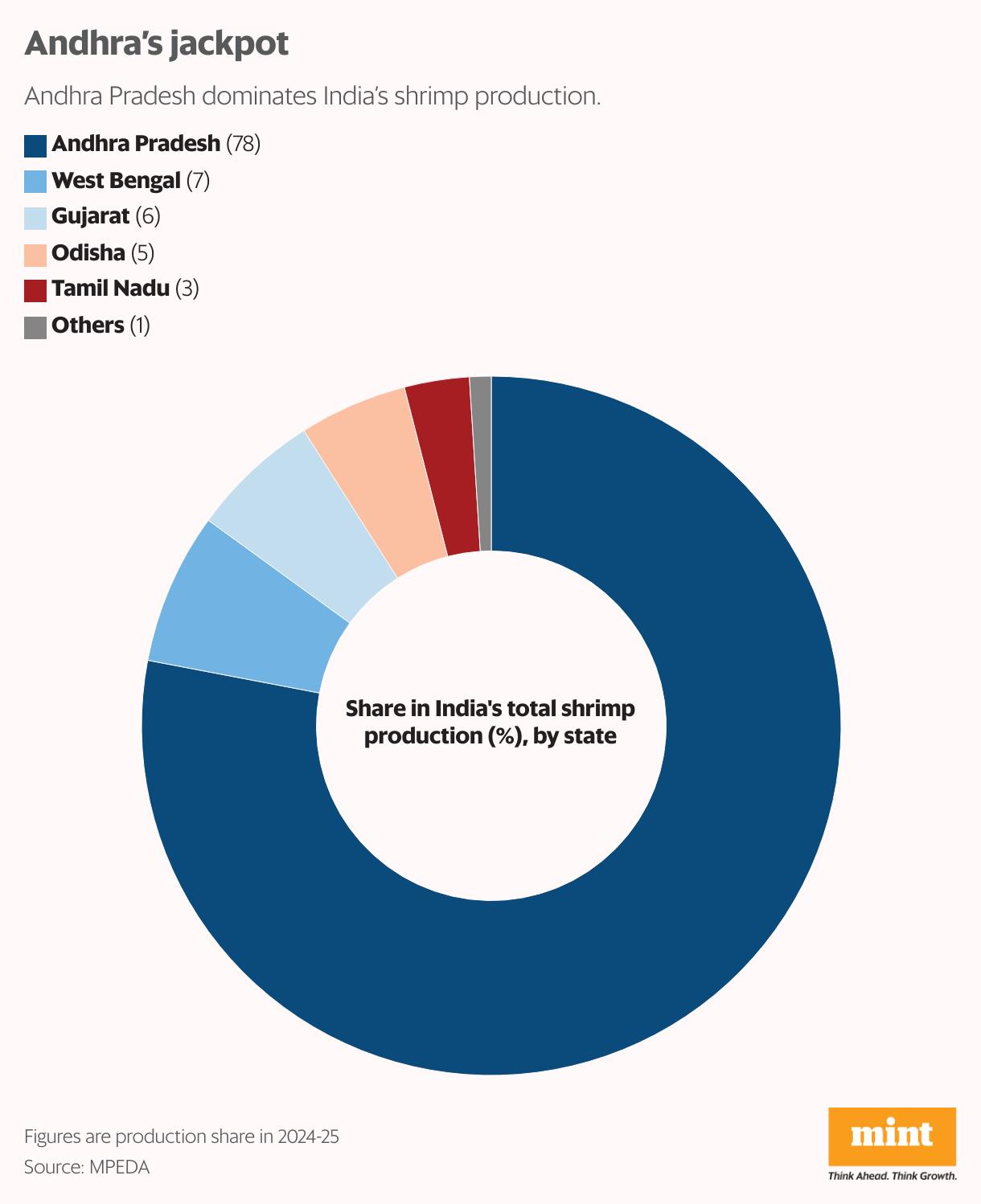

Shrimp exports, at $5.2 billion, accounted for 70% of India's $7.4 billion seafood exports in 2024–25. The US is the biggest market and India caters to 40% of the country's demand annually. Other major buyers are China, the European Union (EU), South-East Asian countries, and Japan. Andhra Pradesh is the largest cultivator of shrimp, accounting for 78% of India's overall output of 1.1 million tonnes (mt) in 2024-25.

“The high tariff has made us uncompetitive," said Pavan Kumar, national president, Seafood Exporters Association of India and a shrimp exporter based in Visakhapatnam. Only exporters with long-term contracts with big retail chains are supplying, and that, too, at lower volumes. Spot buyers, who lift major volumes, have moved away from India to countries such as Ecuador and Indonesia, he added.

According to Shrimp Insights, a global shrimp sector consultant, India's year-on-year exports to the US crashed by 43% in August, while overall volumes declined by 9%. Some financially weak farmers in Bhimavaram have begun shifting to farming fish, such as Roopchand, Rohu and Katla.

But not everyone is despondent. A few see opportunity in this crisis.“We needed this slap from Trump," said Manoj Sharma, a Gujarat-based farmer who produces 1,000 tonnes of shrimp every year. For too long, he explained, the Indian shrimp sector has remained within its comfort zone depending heavily on the US and ignoring the domestic market.

There are other challenges, as well. In recent months, shrimp farmers have been battling multiple diseases, such as white spot viral disease and running mortality syndrome (caused by virus/bacteria), which have reduced the survival rate to less than 50%. Continuous farming and poor soil maintenance has increased the risk of pathogens that cause various diseases. Lower prices, coupled with lower output, mean that farmers barely make any money.

“We have not invested enough in disease identification and control. Today, low survival rate is the biggest cost a farmer pays," said Balasubramaniam V., general secretary, Prawn Farmers Federation of India and a large farmer in Tamil Nadu's Nagapattinam district.

This can be tackled effectively if India has its own indigenous species which will be more disease resistant, he added. Indian farmers usually farm Vannamei, a native of the Pacific Ocean.

“We will be thankful to Trump in five years, if the industry takes up these challenges now," Sharma said.

Vannamei vs Black TigerBut such thoughts are far from the minds of Bhimavaram's shrimp farmers. They are more worried about the short-term. The emergence of this town, located 140 kilometres east of Vaijayawada, as the nerve centre for shrimp farming in Andhra Pradesh, coincided with the rapid growth of India's exports. In 2011, when Bhimavaram began farming shrimp, exports were less than ₹6,000 crore. Today, they rake in ₹45,000 crore.

As one approaches the town, lush green paddy fields give way to large ponds with bio-security fencing made of a ubiquitous green fabric. Each pond has multiple aerators. They are needed to ensure adequate oxygen levels. Some farms have thin wires running across the length and breadth of the ponds to keep birds out. The town survives and thrives on aquaculture.

View Full Image

Aerators in operation at a farm in Bhimavaram that ensure adequate oxygen in the ponds. (N. Madhavan)

“We shifted out of paddy in the 1990s as the area, being low lying, was prone to flooding during monsoon. Initially we opted for fishing but then moved to shrimp in a big way after the Vannamei variety became popular," explained Raju.

Nellore, another Andhra Pradesh town down south, was the shrimp capital of India until recently. At the time, Black Tiger prawns, a large species of marine shrimp, were in demand. Around 2006, the world began shifting to Vannamei or pacific white prawns, for reasons more economic than the taste.

Vannamei requires less or almost zero salinity to farm. This means that they can be raised farther from the sea-Bhimavaram is located about 25 kilometres inland. This species also allows higher stocking. A farmer can raise as many as 100,000 shrimp on an acre-sized pond as against 25,000 in the case of Black Tiger prawns.

Also, Vannamei requires just 90-120 days of cultivation. Black Tiger prawns, on the other hand, have to be grown for up to 180 days.

In short, Vannamei was more attractive for the entire ecosystem. Lower farming time meant farmers could do three crop cycles a year, exporters could scale up their operations and retail chains had an assured supply. Today, Vannamei accounts for 90% of the shrimps raised across the world. The Black Tiger prawn's share has declined to just 9%.

How shrimp are farmed

A typical cycle, Raju explained, starts with sourcing of shrimp seeds from hatcheries that import the broodstock (parent shrimps) from the US.

The seeds are then grown in large ponds, each measuring five acres or more for 90 to 120 days. The challenge here is to maintain the water quality and provide the right quantum of feed.“The first 60 days are critical as the shrimp grows to weigh 100 grams," explained Pavan Nadimpalli, a cultivator with a 3-acre farm. He also operates one of the many aqua labs that dot the town. They are needed to test the water quality and health of the shrimps periodically.

At 60 days, even if disease strikes, the farmer can harvest and recover part of the cost from the unaffected stock.

A farmer gets around ₹220 per kg for '100-count', which is about 100 shrimps, and that is a break-even price at current costs, he added. The price increases as the count drops. A '30-count' (30 shrimps make up 1 kg) fetches a price of ₹400 per kg. For that, the shrimps have to grow for more than 90 days. Once the shrimp is harvested, it is frozen and taken for processing before export.

“We make money only if we are able to cultivate shrimp for a longer duration. That is possible only if there are no diseases. If disease strikes before 60 days, the crop is totally lost," said Krishnam Raju, another Bhimavaram farmer. In recent cycles, he and his fellow farmers have struggled to farm shrimp beyond 60 days.

Indigenous remedyThe latest incidence of disease is alarming, admitted Balasubramaniam of the Prawn Farmers Federation of India. What is more alarming is that the pathogen that is causing the disease and spreading like wildfire is yet to be identified.“The disease typically strikes 45 days after the seed is purchased. Within a week 10% of the crop is lost. In four weeks, if not harvested, 50% is gone," he added.

Diseases have killed the aquaculture sector in South East Asian countries such as Thailand and Taiwan in the past. If not tackled on a war footing, Indian shrimp output could fall sharply, he warned.

The increase in cases of disease has cast doubts on India's approach to genetic selection. The government follows a pathogen exclusion approach. It allows import of pathogen-free broodstock (parent animals), which are then mated in India by hatcheries to produce eggs. This approach, scientists say, has worked well so far, causing shrimp production and exports to grow rapidly. But the rise in pathogens from water and soil is testing this model. Calls have been made to adopt the pathogen exposure approach that countries such as Ecuador follow.“In Ecuador, they constantly expose the shrimps to various pathogens and build their immunity. Their success rate, as a result, is as high as 85%," said Balasubramaniam.

The long-term solution, both farmers and exporters agree, is developing an indigenous broodstock that can handle local conditions and pathogens better.“Vannamei has been around for more than a decade. The scientific community should have looked into this much earlier," rued Kumar from the Seafood Exporters Association.

Double whammyThough India exports shrimp to over 90 countries, the bulk of the volumes goes to the US, China and the EU. Exporters love the US market as it takes up huge volumes at premium prices. Other markets are not that attractive. China, the second-biggest market, is very price conscious and prefers smaller sizes. The EU, where each of the 27 nations has different tastes and rules, is a compliance nightmare.

But India's reliance on the US market faces another challenge apart from Trump's high tariffs. A couple of senators have proposed 'The Indian Shrimp Act', which if passed, will impose an anti-dumping duty of up to 40% over and above the existing tariff. Their grouse: India is dumping shrimp in the US at cheap prices. The US currently has an anti-dumping duty of 2.49% and a countervailing duty of 5.27% on shrimp, taking the effective tariff to 58%. Experts opine that such efforts have been made in the past but have failed. Nevertheless, there is fear within the industry because of the prevailing political environment in the US.

View Full Image

A couple of US senators have proposed 'The Indian Shrimp Act'. (Pixabay)

In light of these developments, farmers want exporters to reduce their reliance on the US by strengthening traditional markets and entering new ones. Japan and Russia can be tapped more, they say.“Japan has been importing seafood from India for years. Their economy is stagnant and the population is aging. Volumes are low," said Selwin Prabhu of Tuticorin-based Nila Seafoods Pvt. Ltd, a large exporter. He is also the Tamil Nadu region president of the Seafood Exporters Association. Efforts are on to push harder into the EU and Russia.

But the association is not letting go of the US.“We took two decades to develop the lucrative US market. We can't lose it," he added.

The trade body is seeking help from the government to tide over the current tariff-created crisis. The finances of exporters are stretched, and banks, having placed the sector in the 'red category' (signals high-risk), are tightening the screws. What is happening is no fault of the industry, Kumar said, seeking some form of temporary hand holding. If the US buyers shift to other markets such as Ecuador, the shrimp sector will be hurt irrecoverably.

Local potentialFarmers such as Manoj Sharma don't agree. While they accept the importance of the US market, they fault policymakers for not exploring the domestic market at all.“Of the 150 crore Indians, 74% are non-vegetarians and if they consume even 100 grams of shrimp each, the demand will be 1.2mt," said Sharma. This is more than the industry's current output. India's domestic shrimp consumption is estimated at 140,000 tonnes annually, barely a tenth of Sharma's projection.

A strong domestic market could supplement exports.“Indian cuisine prefers small shrimps, which are anyway exported at low prices," said Balasubramaniam. Shrimp is also a healthy food as it is high in protein, Omega 3, low on saturated fat and can raise good cholesterol, he added. Awareness is low on its health benefits.

A strong domestic market could supplement exports. Indian cuisine prefers small shrimps, which are anyway exported at low prices.According to Sharma, a concerted effort is needed to develop the local market.“The green revolution (food grains), the blue revolution (milk) and the pink revolution (meat) focussed on meeting domestic demand. Why is the blue revolution (sea food) export focused?" he questioned. He blamed exporters for thwarting the development of domestic demand for shrimps.

The exporters, however, disagree.“We are for a strong domestic market but prices are very low and this will hurt returns of farmers," said Kumar. That will be the case if export volumes are diverted to satisfy local tastebuds.

There is huge headroom to increase production though-India uses just 10% of the 1.2 million hectares of its land under brackish water, which cannot be put to any other productive use, to farm shrimp. Strong domestic demand, at a time when exports to their biggest market face a dire threat, may be just what India's shrimp farmers need.

Key Takeaways-

Shrimp accounted for 70% of India's $7.4 billion seafood exports in 2024–25

The US, India's largest market, imports 40% of its annual requirement from here

Donald Trump's tariffs now threaten to take Indian prawns off the table in the US

High duties imposed have made those imported from India uncompetitive

Adding to the woe, in recent months, shrimp farmers have been battling white spot viral disease and other infections on their farms, which have lowered the survival rate sharply

Developing an indigenous broodstock that can handle local conditions and pathogens better is a long-term solution

A strong domestic market could supplement exports

Exporters also plan to tap the markets of Japan and Russia

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the

information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept

any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images,

videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information

contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright

issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Comments

No comment