Should We Decide By Lottery Who Gets A Medical Treatment First?

Our recent study involving more than 15,000 people across 14 countries found that the public preferred allocation by expert medical committees over lotteries for scarce COVID vaccines .

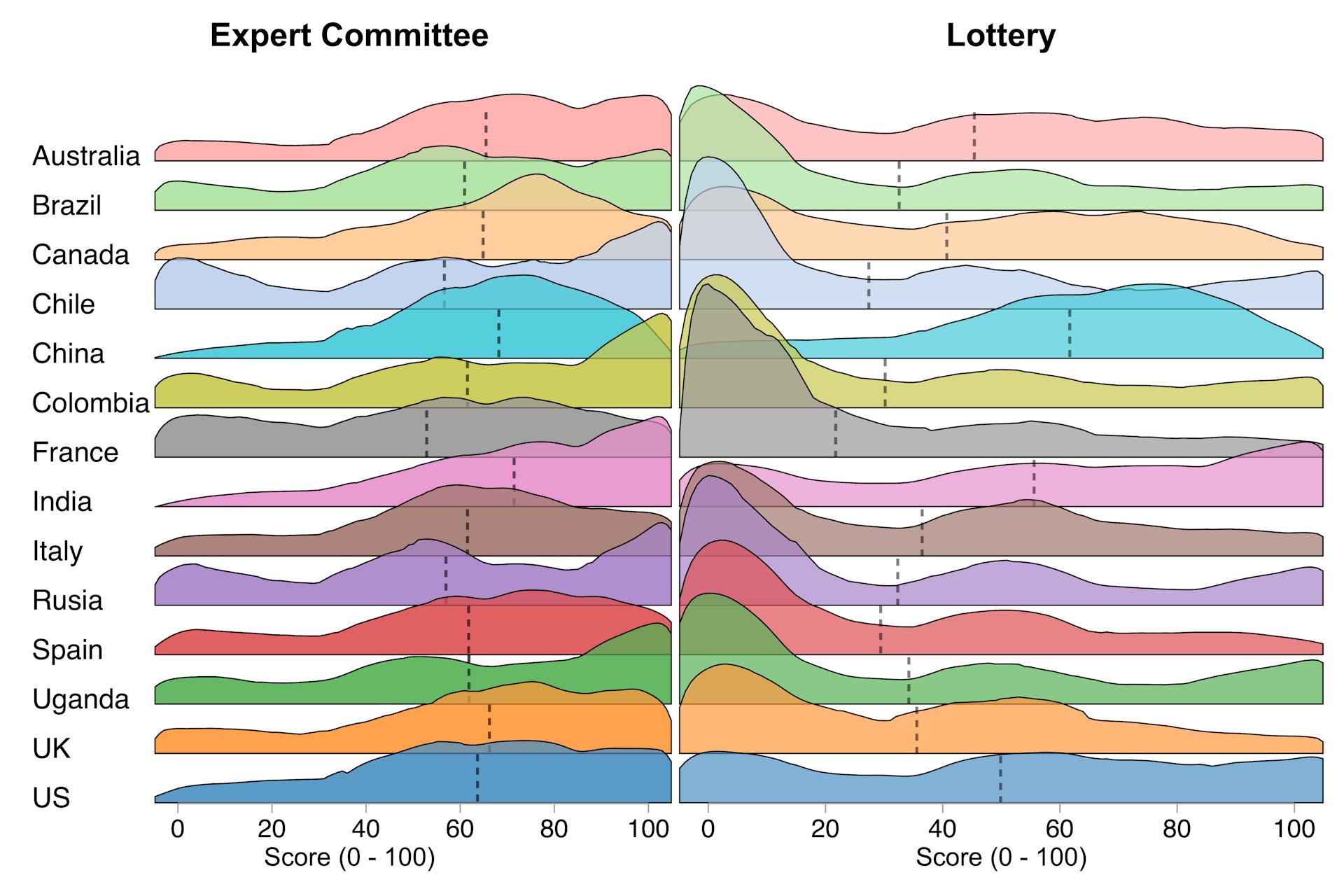

Respondents were presented with a scenario: a hospital wanted to vaccinate all 1,000 of its nurses but had only 500 doses of a COVID vaccine available. Some were asked whether they agreed that an expert committee was an appropriate way to make the decision; others were asked whether they agreed that a lottery was an appropriate way. Agreement with each method was measured on a scale from zero (strongly disagree) to 100 (strongly agree).

On average, expert committees scored 61, compared with just 37 for lotteries. While expert allocation was more acceptable everywhere, support for lotteries varied sharply across countries – from strikingly low in France and Chile to relatively high in China, India and the US.

Distribution of agreement with the appropriateness of allocation by lottery and expert committee. CC BY

In theory, lotteries are fair when used for people who would benefit equally from treatment. They treat people with equal need equally and avoid rewarding those who happen to live closer to hospitals or who are better connected.

Many ethicists have proposed using them when it is hard to make decisions about life-saving treatments. For example, when kidney dialysis first became available in the 1960s, lotteries were discussed as a tie-breaker for equally eligible patients.

While ethicists often focus on fairness in principle, our results suggest that fairness alone may not be enough to persuade the public if the process feels random or impersonal.

During the early COVID pandemic, ethicists again argued for random allocation of potentially life-saving treatments. In the US, several National Academies even recommended lotteries for prioritising vaccines when“no further identifiable risk-based differences” existed between groups – that is, patients of the same age and health status.

Despite these arguments, lotteries were rarely used in practice during the pandemic. Our study suggests that the public was not supportive.

But cultural familiarity with lotteries also matters in terms of which nations will or won't accept them. In India, lotteries are used to allocate school places and public housing . In China, they decide who gets car licence plates in crowded cities. And in the US, a green card lottery allocates immigration visas. In these countries, support for healthcare lotteries was noticeably higher.

In the US, some green cards are allocated by lottery. kurgenc/Shutterstock Luck of the draw

It is difficult to know whether existing lotteries for public services create acceptance, or whether they were introduced because public attitudes were already favourable. Either way, familiarity seems to make lotteries more acceptable.

Scepticism about healthcare lotteries is understandable. Yet committees are not perfect either – they can be slow, inconsistent, or swayed by politics or prejudice. Importantly, during the COVID pandemic, government expert committees in different countries came up with a wide variety of recommendations on who should be prioritised to receive the vaccine first.

If used, lotteries should be implemented in conjunction with medical guidelines. For example, during the COVID pandemic, the UK government prioritised access to vaccines largely based on five-year age bands starting with the oldest groups.

While allocating COVID vaccines based on age criteria was seen as appropriate medically, the order in which people should be vaccinated within an age group is less clear. For example, when rolling out the initial COVID vaccine, there were around 3 million people aged 65 to 69 in the same risk-based priority group, and vaccinating them all simultaneously was impossible.

To avoid vaccinating on a“first-come, first-served” basis that could reward proximity or privilege, a lottery could have been used to decide when each person in this group would receive their vaccine. Such a vaccine lottery featured in the 2011 film Contagion , but was hardly used during the actual pandemic.

The COVID pandemic is over, but future disease outbreaks are inevitable. We should think now about whether lotteries should play a role in allocating scarce treatments or vaccines next time.

For lotteries to be seen as a legitimate way to allocate healthcare, governments need to engage with the public and trial the approach. In 2008, the US state of Oregon used a lottery to select participants for limited Medicaid (a public health insurance programme) slots.

Lotteries remain one of the fairest tools we have when medical differences are otherwise equal. Next time, rather than treating lotteries as unthinkable, we should be ready to use them, with public understanding and trust already in place.

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the

information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept

any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images,

videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information

contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright

issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Most popular stories

Market Research

- Pepeto Presale Exceeds $6.93 Million Staking And Exchange Demo Released

- Citadel Launches Suiball, The First Sui-Native Hardware Wallet

- Luminadata Unveils GAAP & SOX-Trained AI Agents Achieving 99.8% Reconciliation Accuracy

- Tradesta Becomes The First Perpetuals Exchange To Launch Equities On Avalanche

- Thinkmarkets Adds Synthetic Indices To Its Product Offering

- Edgen Launches Multi‐Agent Intelligence Upgrade To Unify Crypto And Equity Analysis

Comments

No comment