Why Kashmir's Oldest Performers Are Disappearing

File photo

By Rayees Wathori

The sound of the dhol once rolled across villages in Kashmir like a call to prayer. The nagara answered with its hollow boom, and the high-pitched surnai followed like a shepherd's whistle, gathering people from fields and lanes toward the village square.

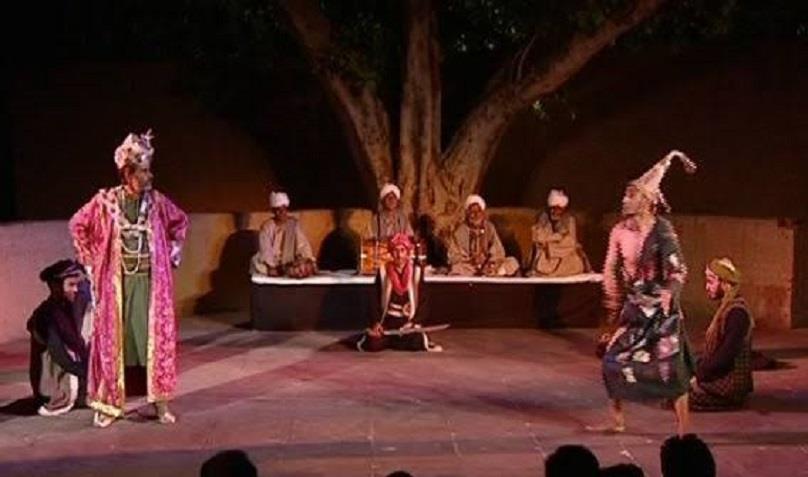

This was how Bhand Pather began, an art form that needed no stage lights, microphones, or curtains. Its stage was the earth, its roof the sky.

The Bhands, Kashmir's folk performers, arrived in bright costumes and wooden masks. They played clowns and kings, landlords and peasants, policemen and cheats. Their stories carried laughter, but their satire was sharp.

They mocked corruption, exposed injustice, and reminded rulers that people were watching. They entertained villagers but also educated them, through jokes that often carried more truth than sermons.

Read Also Bhand Pather and Fading Laughter of Kashmir Shehlun Play Showcased At ChararshariefFor centuries, Bhand Pather embodied the spirit of Kashmiriyat: secular, communal, and rooted in oral tradition.

It was a theatre of resistance and memory, where dissent hid safely in humour. In villages where illiteracy was once high, it was also the people's university.

That rhythm has almost stopped.

Decades of discord silenced the Jashn Gahs, the festival grounds where these performances once drew crowds. Situation made it impossible to gather. Fear replaced laughter. And with time, televisions and smartphones lured people indoors, where global entertainment was available at a touch.

The communal square, the heartbeat of folk culture, was replaced by private screens.

This shift was more political and economic, than technological.

Folk artists were never given state protection in the way classical arts were. No significant cultural policy in Kashmir prioritized Bhand Pather. Government grants for folk theatre are negligible, barely enough to support a handful of performances each year.

The Jammu and Kashmir Academy of Art, Culture, and Languages lists Bhand Pather in its records, but funding is inconsistent and symbolic.

By contrast, Bollywood productions shot in Kashmir receive far more visibility and support than Kashmiri folk forms that are centuries old.

The consequences are severe.

Most Bhands live on the margins, struggling to feed their families. Many who once performed satire for kings and villagers now work as labourers, breaking stones, pulling carts, and doing construction.

Their children do not inherit masks or scripts. They inherit poverty.

Without income or dignity, the folk stage collapses. The erosion is cultural as well as economic: a whole ecosystem of artisans, mask makers, musicians, and storytellers disappears.

Losing Bhand Pather means erasing a record of Kashmiri life that no archive can replace.

Every folk play carried fragments of history, like how people celebrated weddings, mocked tax collectors, and voiced anger against power.

If this theatre dies, we lose a mirror that reflected ordinary Kashmiri lives for centuries.

Modern entertainment cannot fill that gap. A Netflix drama may thrill us, a TikTok video may make us laugh, but they do not carry the echo of our soil. They do not turn neighbours into a community for an evening, laughing together in the open air.

Revival requires policy, investment, and respect. Performers should be paid wages that match their cultural value. Cultural institutions should sponsor regular festivals across Kashmir. Folk theatre should be included in school curricula, so children learn the satire of their own ancestors.

Digital platforms must be used to archive and circulate performances so that they travel beyond the valley, gaining recognition in India and abroad.

Equally important, the content must evolve.

New plays should address issues young audiences care about, like unemployment, climate change, and migration, while keeping the traditional form intact.

In my own experience at Anant National University, I adapted the Kashmiri folk play Shikargah with students from across India. Using traditional Bhand masks, they retold an old story in a way that connected with contemporary audiences at the international WITH Festival.

The response was proof that this theatre can still move people if given space.

There is precedent. Across India, regional folk traditions, including Yakshagana in Karnataka, Tamasha in Maharashtra, and Jatra in Bengal, have survived through state support and community respect. Kashmir deserves the same for Bhand Pather.

If Karnataka can sustain over 200 Yakshagana troupes with government patronage, why can't Kashmir do the same for its Bhands?

Bhand Pather is theatre disguised as comedy, protest disguised as song, and collective memory disguised as play.

Its future depends on whether we treat it as heritage to be mourned, or as a living art to be nurtured.

We should not wait for the last dhol to fall silent in an empty Jashn Gah. The voice of Kashmir's folk theatre is still here, waiting for us to listen, respect, and revive.

-

- The author is an artist-in-residence at Anant National University, working to revive Kashmir's folk theatre traditions.

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the

information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept

any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images,

videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information

contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright

issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Most popular stories

Market Research

- Japan Well Intervention Market Size To Reach USD 776.0 Million By 2033 CAGR Of 4.50%

- Vietnam Artificial Intelligence Market Size, Share, Growth, Demand And Report 2025-2033

- Industrial Hose Market Size, Trends, Growth Factors, Latest Insights And Forecast 2025-2033

- Nutritional Bar Market Size To Expand At A CAGR Of 3.5% During 2025-2033

- What Does The Europe Cryptocurrency Market Report Reveal For 2025?

- North America Perms And Relaxants Market Size, Share And Growth Report 2025-2033

Comments

No comment