New Cold War Proxy Conflict Brewing In Myanmar

But as the conflict between the State Administration Council (SAC) junta and a proliferating array of ethnic and political resistance armies escalates, the rivalry between the world's two big blocs could yet determine the outcome of Myanmar's increasingly vicious civil war.

On one side, the US is supporting the anti-coup National Unity Government (NUG) and by extension its affiliated People's Defense Forces armed groups scattered across the country. On the other, China and Russia are more clearly, although not always overtly, in the junta's camp.

With its substantial and geostrategically important investments in Myanmar, China has the biggest great power interest in the war's direction and outcome.

While Beijing

is playing both sides of the war

-

selling military hardware to the

SAC

and turning a blind eye to Chinese weaponry ending up in the hands of some of the ethnic resistance armies -

it clearly doesn't want the conflict to spiral out of control to the degree it hurts or threatens its in-country interests.

The US, for its part, appears to have refrained from directly providing the various armed groups fighting the junta with weapons and has confined its support to“non-lethal” aid to the NUG, which notably maintains an office in Washington DC.

If the US sought to escalate the Myanmar war into a New Cold War proxy theater, targeting China's big-ticket interests in the country would be a logical tactic.

Significantly, the many armed groups opposed to military rule have so far refrained from targeting China's interests in the country, including the gas pipelines that run the length of the country and thus would be easy to attack or disrupt.

If the US wanted to be more overtly involved at the battlefield level, it would need to do so through Thailand, which like China has no interest in stirring instability that could spill over its borders in a bigger way.

Thailand also relies on Myanmar's natural gas and so has an incentive not to rile the generals through any hint it may be funneling arms to insurgent groups. The US has thus seemingly focused its diplomacy on pressing the Thais to turn a blind eye to the NUG and other exile forces that operate from Thai soil, including in the border town of Mae Sot.

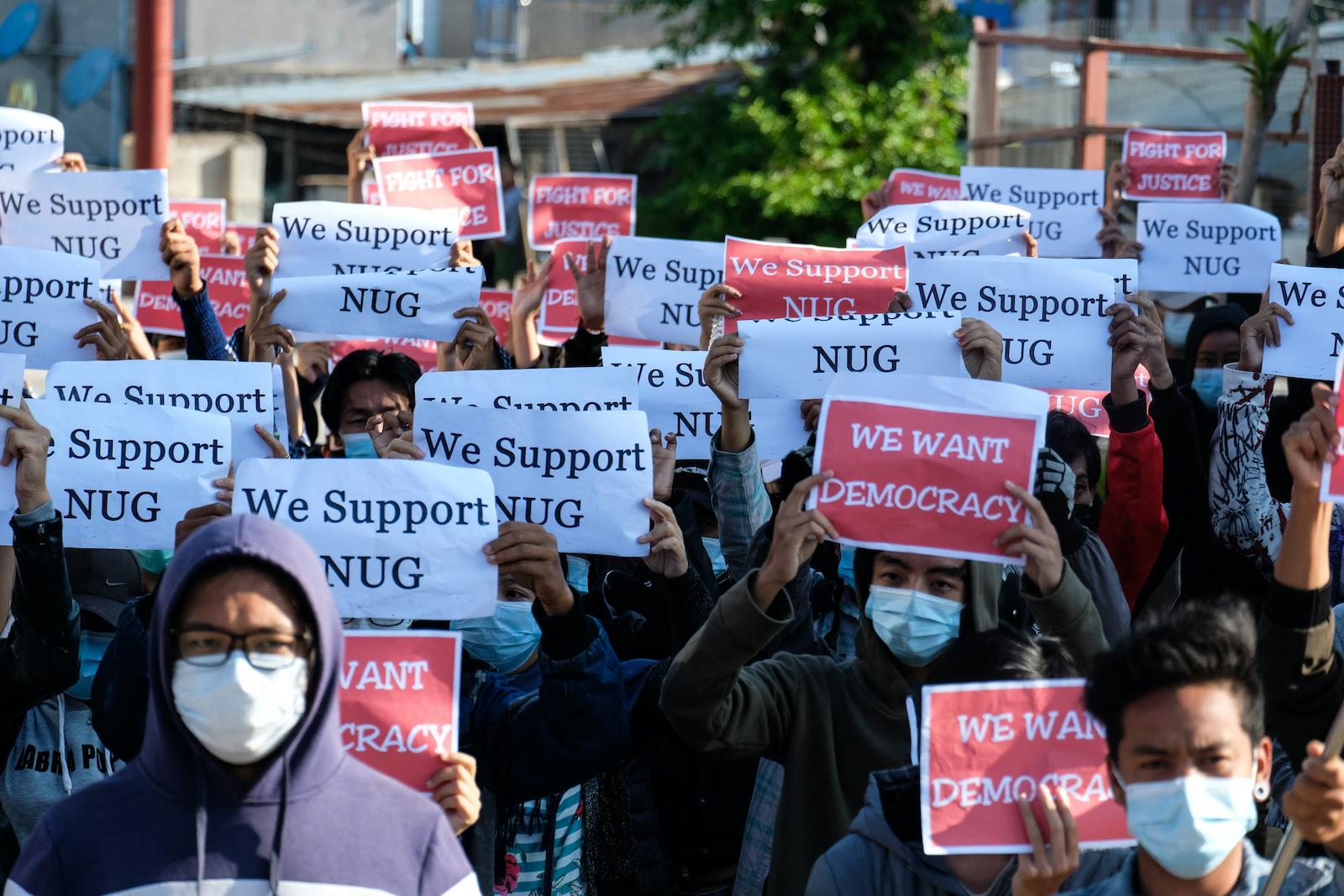

Protesters hold posters in support of the National Unity Government (NUG) during a demonstration against the military coup on 'Global Myanmar Spring Revolution Day' in Taunggyi, Shan state, on May 2, 2021. Photo: Asia Times Files / AFP / Stringer

To be sure, the US may still be providing more clandestine aid to the resistance than it publicly acknowledges, including potentially through elements in the Thai military known to be sympathetic with certain ethnic armies. But if so it has not been to a degree or manner that could turn the war or threaten China's position.

China's reasons for aspiring to influence, contain and even control Myanmar's conflict are obvious and many. Myanmar is the only immediate neighbor which provides China with convenient, direct access to the Indian Ocean, bypassing the contested South China Sea and congested Strait of Malacca, which the US could potentially block in a conflict scenario.

Such a connection is vital for the export of Chinese goods to the outside world as well as the importation of fossil fuel from the Middle East and minerals from Africa. That is why China has built oil and gas pipelines from the shores of the Bay of Bengal to its southern province of Yunnan and plans to construct highways and a high-speed rail along the same route.

As part of the plan, Chinese state-owned entities are developing a US$7.3 billion deep-water port at Kyaukphyu on the coast of Myanmar's Rakhine State and a US$1.3 billion special economic zone (SEZ), which includes an oil and gas terminal.

Those projects are located at the lower end of the 1,700-kilometer China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC) connecting Kunming in China's Yunnan province to the Indian Ocean.

As such, Beijing will do everything in its power to protect its geostrategic interests - and it does not take lightly any attempt by what it considers outsiders to interfere with its long-term plans for Myanmar and the region.

Japan's service firms to hurt the worst in China split

Who will be Iran's next supreme leader?

Kim a mortal menace or playing mind games?

Having supported the insurgent Communist Party of Burma (CPB) in the late 1960s and early 1970s, China's foreign policy changed after the death of Mao Zedong in 1976 and the subsequent rise of reformist Deng Xiaoping. His new China no longer attempted to export revolution; now it was all about economic development and the establishment of trade with the outside world.

The aftermath of the Myanmar military's bloody suppression of a pro-democracy uprising in 1988 provided China with the opening it craved. While the West imposed sanctions and boycotts against the junta in Yangon, China began to promote cross-border trade - and in the decade after the massacres, China sold more than US$1.4 billion worth of aircraft, naval vessels, heavy artillery, anti-aircraft guns, and tanks to Myanmar.

China also helped Myanmar upgrade its naval bases along the coast and on islands in the Bay of Bengal and the Andaman Sea. Chinese-supplied radar systems were installed in some of these bases, and it is reasonable to assume that China's security services benefited from the resulting intelligence.

But the fiercely nationalistic Myanmar military never felt wholly comfortable with its heavy dependence on China for arms and supplies. The Chinese were treating Myanmar as a client state and many Myanmar army officers could not forget that thousands of their soldiers had been killed by the CPB's Chinese-supplied guns before that insurgency collapse in 1989.

In order to diversify its sources of procurement, the Myanmar military began to cultivate defense ties with Russia. Myanmar became a lucrative market for the Russian war industry. Myanmar bought Russian-made MiG-29s jet fighters and Mi-35 Hind helicopter gunships, both of which are now being used across the country against the resistance.

Two Myanmar fighter jets seen firing shots during an exercise in Meiktila in 2019. Image: State Media

Russia also shipped heavy machine guns and rocket launchers to Myanmar and before the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, Russian-made tanks and armored personnel carriers were obtained through dealers in Ukraine. Moreover, Russian military instructors have been spotted at a Myanmar airfield, presumably to assist in the maintenance of the attack helicopters.

Such training is not new, however; probably as many as 5,000 Myanmar soldiers and scientists have studied in Russia since the early 1990s, more than from any other Southeast Asian country.

It is unclear to what extent Russia, which after its invasion of Ukraine needs all the military hardware it has at its disposal, has been able to continue selling weaponry and parts to Myanmar.

But in February 2023, Russia's state-owned nuclear corporation Rosatom and the SAC's Ministry of Science and Technology signed a memorandum of understanding to build a small nuclear power plant in Myanmar.

A similar agreement was signed in 2007 under which Russia agreed to build a nuclear research reactor in Myanmar, but nothing substantial happened until this new agreement was concluded last year.

While China has geostrategic interests in Myanmar, Russia is more concerned about making money, though Russia's involvement in the war cannot be explained solely in the context of business deals. Significantly, while China and Russia are in lockstep in the Ukraine war, there is little evidence they are acting in tandem in Myanmar.

The erstwhile Soviet Union was once a major power in Asia and also a bitter enemy of not only the United States but also China, which saw the leaders in Moscow as“revisionists” and“traitors” to the communist cause.

The Soviet Union had a close alliance with India and pro-Moscow regimes were in power in Vietnam, Laos and, after the Vietnamese intervention in 1978-79, also Cambodia.

All of that disappeared after the disintegration of the Soviet Union and the beginning of Boris Yeltsin's chaotic rule in Russia, which then became a separate country.

It needed the firmer hand of his successor Vladimir Putin to restore some of the old glory, and now the Chinese became allies in common cause against the United States and its power in the Indo-Pacific region.

Russian influence over its old allies has vanished, but Myanmar has become a willing new partner in Moscow's plans for playing a greater role in regional affairs.

And Russia does not seem to care how and against whom the SAC is using its supplied weaponry. While the Myanmar Army has performed poorly on the ground, it has had to increasingly rely on Russian-supplied air power, including helicopter gunships, which have been strafing resistance-held towns and villages across the country, probably killing thousands of civilians.

China has been more cautious in its dealings with the hugely unpopular SAC. It has not, for instance, like Russia, invited junta leader Senior General Min Aung Hlaing

to make high-profile visits since the coup.

Anti-Chinese demonstrations were held outside the Chinese embassy in Yangon in the coup's immediate aftermath, where angry protesters railed against the Chinese for describing the democracy-suspending putsch as a mere“cabinet reshuffle.”

Myanmar protesters in front of the Chinese embassy in Yangon after the February 1, 2021, coup. Photo: Facebook

According to a United Nations report released on May 17, 2023, China has sold at least $267 million worth of weapons and related material to Myanmar since the coup.

But the resistance in the north is also being equipped with Chinese weapons obtained through the United Wa State Army (UWSA), which grew out of the ashes of the CPB.

By playing both sides, China has been able to sell itself to the SAC as the only outside power that can act as a broker and peacemaker. China helped to negotiate a truce of sorts between some ethnic resistance armies in northern Shan state and the SAC.

And with the Arakan Army, which has also benefited from arms supplied by the UWSA, making significant headway in Rakhine State, it is only a matter of time before China intervenes in that conflict as well.

China has always claimed that it has the right to do so because the war is being fought dangerously close to Kyaukphyu. And, in the process, China can also force Japan's Nippon Foundation, which until now has been the main peacemaker in Rakhine state, out of the area.

The Russians, on the other hand, have been blunter and cruder in their approach. Min Aung Hlaing has been welcomed with open arms in Moscow and Russian Deputy Defense Minister Alexander Vasilyevich Fomin, dressed in his full colonel-general uniform, has attended military ceremonies in Naypyitaw.

On the day before the February 2021 coup, a group of Russians and Myanmar colleagues had a party in Yangon, where the vodka reportedly flowed freely.

Apparently, they were celebrating the opening of a military high-tech multimedia complex in which the children of Min Aung Hlaing have a financial interest. They also reportedly toasted the coup that was going to be launched the following day.

The United States has reacted to these developments with utmost concern and issued statements in support for the struggle“for democracy, freedom, human rights, and justice”

in Myanmar.

Washington has also imposed various sanctions on SAC members and their business interests.

A US aid package provides $75 million for refugee assistance programs in Thailand and India, and $25 million for“technical support and non-lethal assistance” to the NUG, which was set up by the resistance after the 2021 coup.

Smaller amounts have been earmarked for“governance programs, documentation of atrocities, and assistance to political prisoners, Rohingya and deserters from the junta's military.”

Sign up for one of our free newsletters

- The Daily ReportStart your day right with Asia Times' top stories AT Weekly ReportA weekly roundup of Asia Times' most-read stories

At the same time, a massive, new US consulate general is under construction in the northern Thai city of Chiang Mai. In a colorful, online brochure, the project is described as“a concrete sign of our long-term commitment to the people of northern Thailand and the future of our partnership”, and the text goes on to state that the diplomatic mission is“dedicated to serving the local American community or those wishing to travel to the United States.”

Be that as it may, few doubt that it is more specifically part of a wider program to reinforce US intelligence capabilities in the region.

It would be no coincidence that Chiang Mai has been chosen as a strategic listening post.

The Americans first set up a diplomatic mission in Chiang Mai in 1950 which acted mainly as an intelligence station that coordinated support for nationalist Chinese, Kuomintang, forces that had retreated into Shan state in eastern Myanmar after their defeat in the Chinese Civil War.

The US consulate in Chiang Mai later oversaw the gathering of human as well as signals intelligence in the region during the Indochina wars. Local agents were sent across the border and the Americans together with the Thais maintained an extensive network of listening posts in northern Thailand.

The main such facility was located near Udon Thani in northeastern Thailand and consisted of, a large, circular array of Wullenweber antennas which was commonly referred to as the“Elephant Cage” because its shape resembled an elephant kraal. That facility picked up radio traffic from Laos, southern China and North Vietnam while also monitoring Chinese military movements in the region.

Artist's concept of new US consulate in Chiang Mai, Thailand. Image: US State Department Brochure

Most importantly, it served as a military intelligence terminal for communications between the US and its various intelligence sites in Southeast and East Asia. A similar facility was established near Lampang south of Chiang Mai, for the specific purpose of monitoring radio traffic in northern Myanmar and Yunnan.

American Chinese language experts translated intercepted messages into English, and Burmese-speaking Shans translated messages in Burmese into Thai and English. A major target at that time was the China-supported CPB. Over the years, the“Elephant Cages” became obsolete and today there are more advanced and sophisticated ways of monitoring movements in cyberspace, as well as on the ground.

The New Cold War may not yet be as hot as the previous one was, but it is clear that the Americans and their allies are building a bulwark against China across Asia, seen overtly in the AUKUS, Quad and new Squad multilateral security arrangements geared to contain Beijing's rise.

But the construction of a huge new US consulate general in Chiang Mai and financial support for the pro-democracy forces inside Myanmar are also part of this larger China, and by bloc association, Russia containment strategy.

There is still a long way to go before we see the return to the open Cold War proxy confrontations of the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s. But conflict-ridden Myanmar may well once again find itself in the eye of a new geopolitical storm over which it will have little or no control.

Bertil Lintner is a Thailand-based journalist and author who has written over 20 books on Myanmar, organized crime and regional security issues.

Shawn W. Crispin provided editing, fact-checking and reporting from Bangkok.

Thank you for registering!

An account was already registered with this email. Please check your inbox for an authentication link.

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the

information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept

any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images,

videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information

contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright

issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Comments

No comment