What's In A Label? Rethinking How We Talk About Gender-Based Violence

GBV can include sexual, physical, mental and economic abuse. Coercive control and manipulation in intimate partner relationships are an example, as is sexual assault, child marriages or technology-facilitated violence. And in Canada, GBV disproportionately impacts women and girls.

Read more: Why Canada needs to recognize the crime of femicide - on Dec. 6 and beyond

As GBV evolves across digital and in-person contexts, the stakes of language are especially high.

Drawing on our research and practice, we explore what these labels mean, how they are used and the impact they have on people's lives. Our aim is to support intentional language as part of the broader work of violence prevention, collective action and addressing harm.

Two starting points help anchor this discussion. The first is that when you are in direct contact with someone who has experienced GBV, follow their lead in how they describe their own experience. The second is to recognize that different communities use terms rooted in their own histories that demand our respect, not our translation.

What 'victim' reveals and what it distorts“Victim” centres the harm experienced by individuals and the impacts it has had on their lives. It first gained prominence early in the women's rights movement, when it was deployed to evoke sympathy and action. Today, it remains central to the legal system.

Research indicates that labelling someone as a victim frames them as someone in need of saving or protection rather than being recognized as knowledgeable and capable.

The label has also been criticized for reinforcing the“perfect victim” stereotype, suggesting that only those who appear innocent or socially respectable deserve empathy or justice. This stereotype often dismisses and blames certain groups, including Black women and women with disabilities who face compounded discrimination and disbelief.

Yet some individuals embrace the label of“victim” as an honest reflection of what they endured.

As American writer Danielle Campoamor states:

'Survivor' - the resilience story“Survivor” foregrounds empowerment and resilience. People labelled as survivors are generally perceived more positively than people labelled as victims.

For men who have experienced sexual violence,“survivor” can offer a way to name harm in a context where acknowledging victimization is socially discouraged.

However, the label can shift attention away from aggressors and toward expectations that individuals demonstrate strength or recovery. Healing is not a linear process, and the label of“survivor” can create pressure that a person or community simply“get over it.” These expectations stigmatize people whose healing does not align with socially accepted ideas of recovery or“good” behaviour.

A focus on personal resilience can also reflect society's discomfort with GBV by celebrating endurance rather than confronting the systems that create harm.

“Victim-survivor” has also been proposed as an umbrella term that aims to disrupt the victim/survivor binary, though it can reproduce some of the same pressures attached to both.

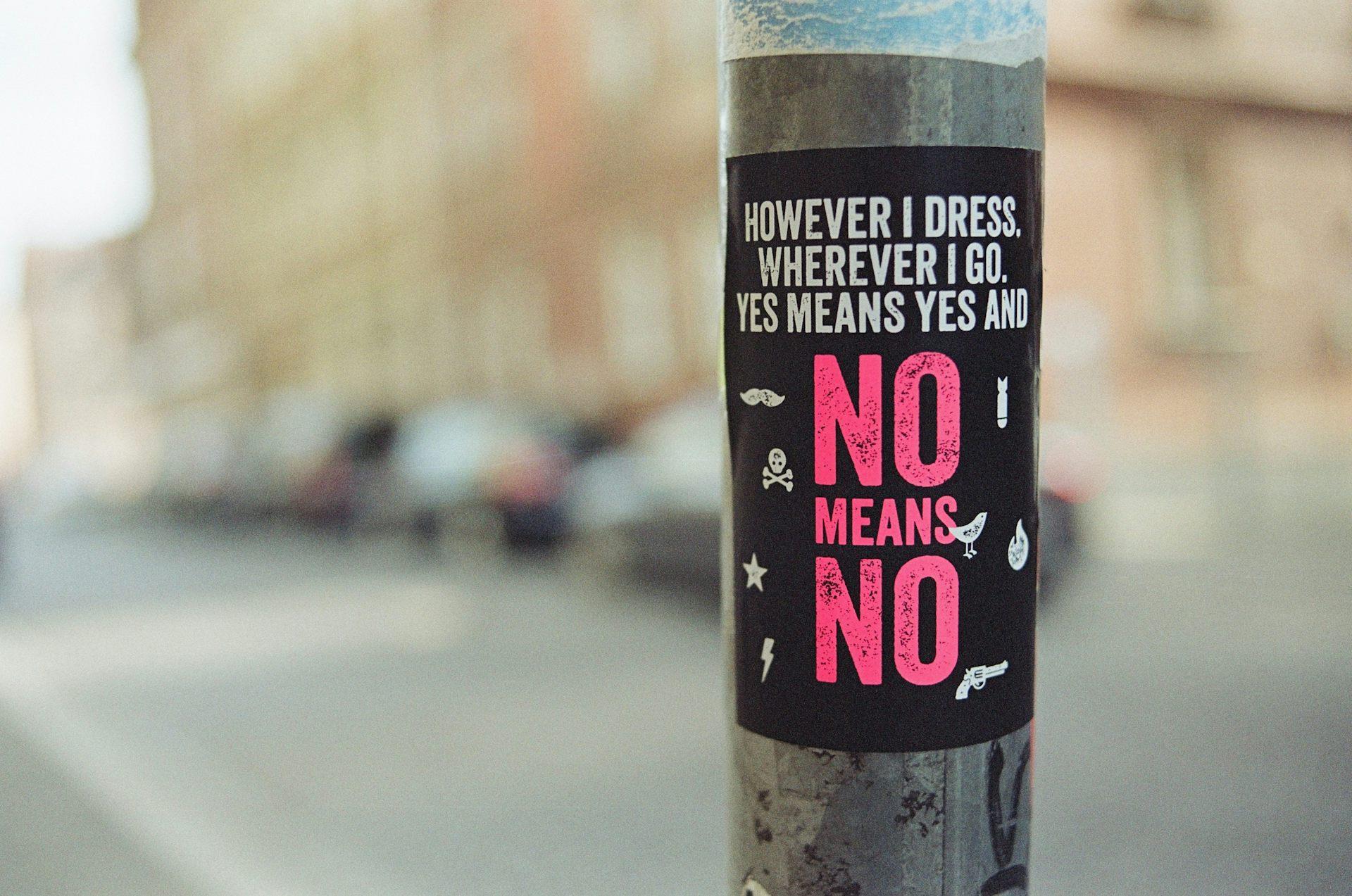

No single label - like victim, survivor or individual who experienced gender-based violence - can fully and accurately summarize experiences of violence. (Unsplash) Does person-first language respect or obscure?

Person-first language, such as“individual who experienced GBV,” emerged from disability activism. It leads with the person rather than the label, offering an alternative to identity-first terms like“victim” or“survivor.”

Person-first language has been found to affirm dignity and emphasize that violence is only one part of a person's story. It highlights individuality and complexity, reflecting the wide range of experiences within this group.

But person-first language can unintentionally portray the person's identity as inherently negative or shameful. It can also individualize violence, obscuring the broader social and political structures that enable it.

Ultimately, the value of person-first language depends on how it is applied and whether it recognizes both personal experience and systemic accountability.

Navigating labels in real-life contextsEvery label captures something true while also missing something else.

The goal is not perfection or consistency; it is intention. Ask: What purpose does this label serve? How is it shaping assumptions about harm and agency? How might you capture what the label misses? Are you imposing one term universally or making space for the multiplicity of language people actually use? If you are speaking to or about an individual, what term do they prefer?

While we recognize that institutional settings often limit the language used, these questions remain useful because they help guide how those terms are applied, offering space to challenge harmful assumptions even when the terminology itself cannot change.

No single label can fully and accurately summarize experiences of violence. Labels often overlap, shift with context and evolve over time.

What matters most is using language that reflects care and respect. Our words should neither confine people to their experiences of violence nor erase the realities of that harm. Intentional language is one way we move closer to a world where GBV is actively named and dismantled.

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the

information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept

any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images,

videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information

contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright

issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Comments

No comment