The UAE Is Leaving Saudi Arabia Squeezed In Yemen

The new status quo looks like a fait accompli for the creation of a separate southern state. It has left Yemen's internationally recognised government, the Presidential Leadership Council (PLC), squeezed between a pole in the south and a state run by the Iran-backed Houthi militia in the north.

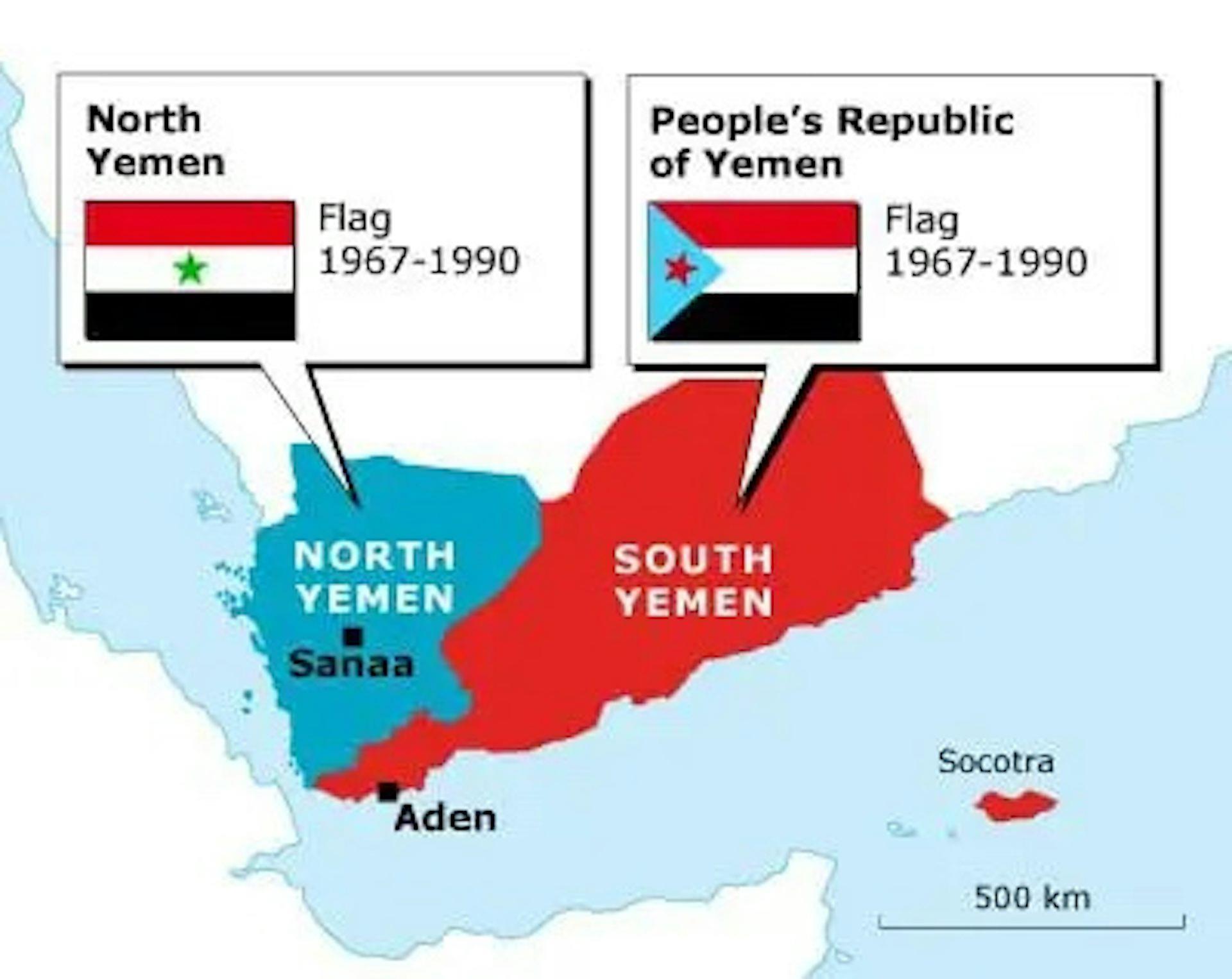

The STC taps into memories of the People's Democratic Republic of Yemen which, until 1990, gave southerners their own state. Yemen's 1990 unification produced one flag, but many people in the south never felt they joined a shared political project.

These grievances led to a brief civil war in 1994. This war ended with northern victory, purges of southern officers and civil servants, and what many in the south still describe as an occupation rather than integration.

Yemen unified in 1990, with Sana'a as its capital. FANACK, CC BY-NC-ND

By the mid-2000s, retired officers and dismissed civil servants in the south were marching for pensions and basic rights. Those protests turned into al-Hirak al-Janoubi, a loose southern movement running from reformists to hardline secessionists.

And when the 2015 Saudi-led intervention began against the Houthis, which had seized the Yemeni capital of Sana'a the previous year, southern fighters were folded into a campaign to restore a“national” government that had never addressed their grievances.

The STC was formed in 2017 to try and give this crowded field in the south a recognisable leadership. It has a formal president, Aidarus al-Zubaidi, and councils. But in practice it sits at the centre of a web of armed units, tribal groups and businessmen.

Through sustained financial and material backing for the southern armed groups, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) emerged as the midwife of the organisation's creation. Against the backdrop of widespread failed governance in Yemen, the STC project seems to deliver relatively well on security and public services.

In April 2022, several years after the STC's formation, the PLC was created to unite the forces fighting the Houthis. Yemen's Saudi Arabia-based president, Abd-Rabbu Mansour Hadi, resigned and handed his powers over to an eight-member body backed by Riyadh.

The PLC was designed to bridge the various tribal, ideological and political divides in the country. It also aimed to create a platform to coordinate governance and statecraft with a view to engaging the Houthis through diplomacy.

But as it mixes northern and southern leaders, including those from the STC, the PLC has never emerged as a viable hub to merge competing agendas. The inability of the PLC to deliver on its promise to consolidate governance across Yemen has incrementally eaten away at its legitimacy.

Houthi soldiers march in Sana'a during a parade in May 2024 to mark the 34th anniversary of Yemen's unification. Yahya Arhab / EPA A Gulf proxy war

Yemen has turned into a quiet scorecard for two Gulf projects. Saudi Arabia intervened to defeat the Houthis, rescue a unified Yemeni state and secure its own borders. The UAE went in to secure reliable partners, access to ports and sea lanes and control of resources as part of its regional policy.

A glimpse at a map of Yemen today shows it is the UAE whose vision seems to have been realised. Through the STC and a web of allied units, the UAE has helped stitch together a power base that runs across nearly all of former South Yemen. STC-aligned forces hold the city of Aden, sit on much of Yemen's limited oil production and control long stretches of the Arabian and Red Sea coasts.

Control of terrain in Yemen

Pink or blue shaded areas depict territory controlled by the PLC or allied forces, yellow or orange depict territory controlled by the STC or allied forces, green depicts areas controlled by the Houthis. NordNordWest / Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-NC-SA

Key national infrastructure in southern Yemen is now guarded by men whose salaries, media platforms and external ties flow through Abu Dhabi. In return, the UAE enjoys a loyal surrogate on the Gulf of Aden and the approaches to the Bab al-Mandab strait. Saudi Arabia, by contrast, has been left propping up a fragile PLC.

The Houthis remain the nominal enemy for everyone. But, in reality, UAE-aligned units have poured more bandwidth into sidelining Saudi-backed rivals in southern Yemen than engaging the insurgent-turned-state in the north. The UAE now holds leverage over Yemen's crown jewels in the south, while Saudi Arabia shoulders the burden of the narrative of a“united Yemen” with few dependable allies inside the country.

Two-and-a-half YemensFor decades, neighbours Saudi Arabia and Oman as well as most foreign capitals have sworn by a single Yemeni state. The UAE-backed STC project cuts directly across that line, with an entrenched southern order making a formal split far more likely.

If Yemen is carved in two, the Houthi structure in the north does not evaporate; it gains borders, time and eventually a stronger claim to recognition. That would cement a heavily armed ideological authority at the mouth of the Red Sea, tied to Tehran and Hezbollah and ruling over a population drained by war and economic collapse.

Yet, confronted with the multilayered network created by Iran and the UAE in Yemen, Saudi Arabia has few cards to play. It may eventually be forced to concede to a UAE-backed government-in-waiting in the south while the north settles into Houthi rule and territory held by the PLC gets increasingly squeezed.

Oman keeps arguing for a shared table that brings all parties – including the Houthis – into one system. But every new southern flag raised undercuts that goal. For outside powers, a southern client that keeps ports open and hunts Islamist militants is tempting.

The price is to freeze northern Yemen as a grey zone: heavily armed, ideologically rigid and wired into regional confrontation. That outcome cuts against the very unity project Saudi Arabia and Oman have endorsed for years. What is left today are two-and-a-half Yemens – with the half, territory administered by the PLC, looking the least sustainable moving forward.

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the

information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept

any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images,

videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information

contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright

issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Comments

No comment