How Eating Oysters Could Help Restore South Australia's Algal-Bloom Ravaged Coast

Their state is grappling with an unprecedented and harmful algal bloom. The crisis has drawn attention to another, long-forgotten environmental disaster beneath the waves: the historical destruction of native shellfish reefs.

Reefs formed by native oysters, mussels and other aquatic mollusks carpeted more than 1,500 kilometres of the state's coastline, until 200 years ago. In fact, they went well beyond the state border, existing in sheltered waters of bays and estuaries from the southern Great Barrier Reef to Tasmania and all the way around to Perth.

These vast communities of bivalves, which feed by drawing water over their gills, would have helped clean the ocean gulfs and supported a smorgasbord of marine life.

Their destruction by colonial dredge fisheries - to feed the growing colony and supply lime for construction - has left our contemporary coastlines more vulnerable to events like this algal bloom. And their recovery is now a central part of South Australia's algal bloom response.

Dominic Mcafee snorkels over a restored oyster reef at Coffin Bay. Stefan Andrews, CC BY-ND Rebuilding reefs

South Australia's A$20.6 million plan aims to restore various marine ecosystems, with two approaches to restore shellfish reefs.

The first is building large reefs with limestone boulders. These have been constructed over the past decade with some positive results. Four have been built in Gulf St Vincent near Adelaide.

Boulder reefs provide hard, stable substrate for baby oysters to settle and grow on. When built at the right time in early summer, when oyster babies are abundant and searching for a home, oyster larvae can settle on them and begin growing. But these are large infrastructure projects – think cranes, barges and boulders – and therefore take years to plan and execute.

So alongside these large reef builds, the public will have the chance to help construct 25 smaller community-based reefs over the next three years. From Kangaroo Island to the Eyre Peninsula, these reefs will use recycled shells collected from aquaculture farms, restaurants and households using dedicated shell recycling bins. There will soon be a dedicated website for the project.

The donated shells will be cleaned, sterilised by months in the sun, and packaged into biodegradable mesh bags and degradable cages to provide many thousands of“reef units”. From these smaller units, big reefs can grow.

This combined approach - industrial-scale reefs and grassroots restoration - reflects both the scale of the ecological problem and the appetite for public participation.

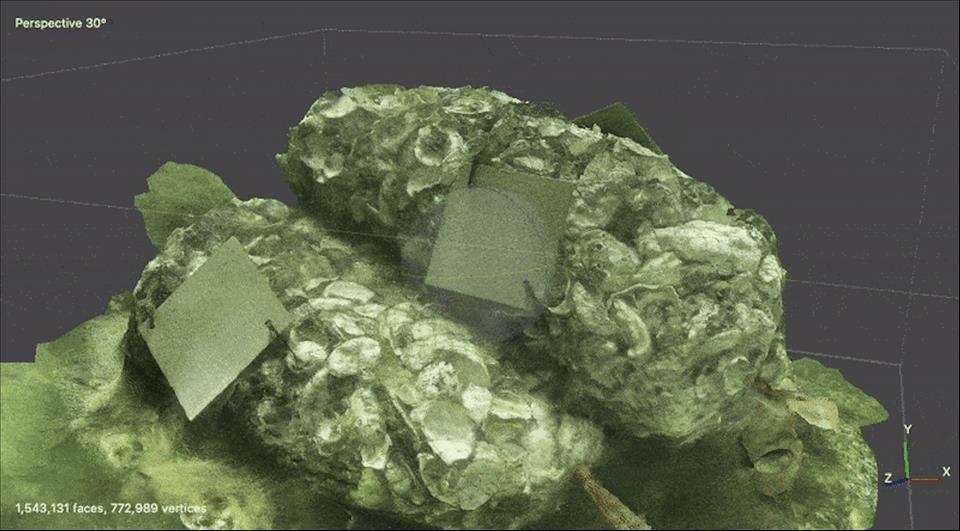

A 3D model of a community-based reef underwater with panels to monitor oyster settlement. Manny Katz, EyreLab, CC BY-ND What about the algal bloom?

Little can be done to disperse an algal bloom of this magnitude once it has taken root. Feeling like powerless witnesses to the disaster, the ecological grief and dismay among coastal communities is palpable. Naturally, attention turns to recovery – what can be done to repair the damage?

This is where oysters come in. They cannot stop this bloom. And their restoration is not a silver bullet for addressing the many stressors facing the marine environment. But healthy ecosystems recover faster and are more resilient to future environmental shocks.

For shellfish reefs, South Australia already has some impressive runs on the board. Over nearly a decade we have undertaken some of the largest shellfish restorations in the Southern Hemisphere. Millions of oysters have found a home on our extant reefs, providing filtration benefits and supporting diverse marine life.

And although the algal bloom has decimated many bivalve communities, thankfully native oysters have been found to have a level of resilience. During a dive last week we witnessed new baby oysters that had recently settled on the reefs, seeding its recovery.

In the past decade we have built a scientific evidence base, practical knowledge, and community enthusiasm for reef restorations that benefits the broader marine ecosystem. This is why shellfish reefs feature so prominently in the algal bloom response plan.

A site of oyster reef restoration in South Australia. Stefan Andrews, CC BY-ND Where will these new reefs go?

We need time to identify the best sites for big boulder reefs. For now, the priority is monitoring the ecological impacts and resilience to the ongoing algal bloom. But work on community-based reef projects has already begun.

These reefs will broaden our scientific understanding of how underwater animals and plants find them. Sites will be chosen based on ecological knowledge and community interest in ongoing marine stewardship.

There are many ways communities can take part. Community involvement and education is a cornerstone of the work, and individuals can recycle their oyster, scallop and mussel shells. The public can also volunteer time to join shell bagging and caging events, and even get involved building the reefs. In time, there will opportunities for the community to help with monitoring and counting the oysters and other critters settled on the recycled shell.

A native oyster reef in Coffin Bay, South Australia. Stefan Andrews, CC BY-ND Future built from the past

The impact of this harmful algal bloom is real and ongoing. But in responding to it, South Australians are rediscovering a forgotten marine ecosystem. Rebuilding shellfish reefs won't fix it - but alongside catchment management, seagrass restoration, fisheries management and improved monitoring and climate action, it is a powerful tool.

With the help of communities, reefs that were once broken, forgotten and functionally extinct, can be returned. It will take time for these reefs to support cleaner waters and richer marine life. But these community initiatives can show people that we all have a role to play in caring for coastlines.

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the

information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept

any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images,

videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information

contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright

issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Comments

No comment