Women Are Still Absent From How History Is Taught And Assessed In England

You only have to take a look recent exam papers to see the problem. For example, when my colleague Catherine Gower and I surveyed 219 GCSE, AS and A-level history papers issued in the summer of 2023, we found only 6% of 991 exam questions directed students to discuss women (37% directed students to discuss men).

A report by the charity End Sexism in Schools, which carried out a survey into the teaching of women in history in earlier years at secondary school, found a similar lack.

Surprisingly, the recently released Curriculum and Assessment Review of England's national curriculum pays scant attention to women and girls. Coverage of gender-related issues in the curriculum as a whole was disappointingly thin.

While the need to recognise a“wider range of perspectives” is cited in the curriculum review, these references are unclear and do not specifically address gender imbalance. There is still no statutory requirement to include women in the teaching of history – even though unrelated government research suggests that misogyny is a serious problem in schools.

No educational system can fully represent the whole of human history. Designing curriculum content is always a matter of choice. Who and what we choose to teach about our shared pasts is critical to the development of young people's identities and empathy, as well as their awareness of local, national and global connections and life experiences dissimilar to their own.

Without government specification, despite the wealth of academic scholarship produced over the past 50 years on women and gender in history, there has been no corresponding imperative to embed this within secondary schools.

While there are teachers who are keen to incorporate women, they face systemic challenges. The assessments set by exam boards, which are influenced by the national curriculum, play a crucial role here. In an era of league tables there is intense pressure on teachers to prioritise assessment-focused content. If topics relating to women are not going to be assessed, it can be a struggle for teachers to include them.

Missing womenOur research focused on exam papers across England, including primary source extracts and mark schemes. One of the most shocking findings was that over one third of the papers – 34.7% – contained no mention of any women at all. They were not mentioned in questions, in the historical sources provided for students to examine, or in mark schemes. By comparison, only one paper out of 219 made no mention of men.

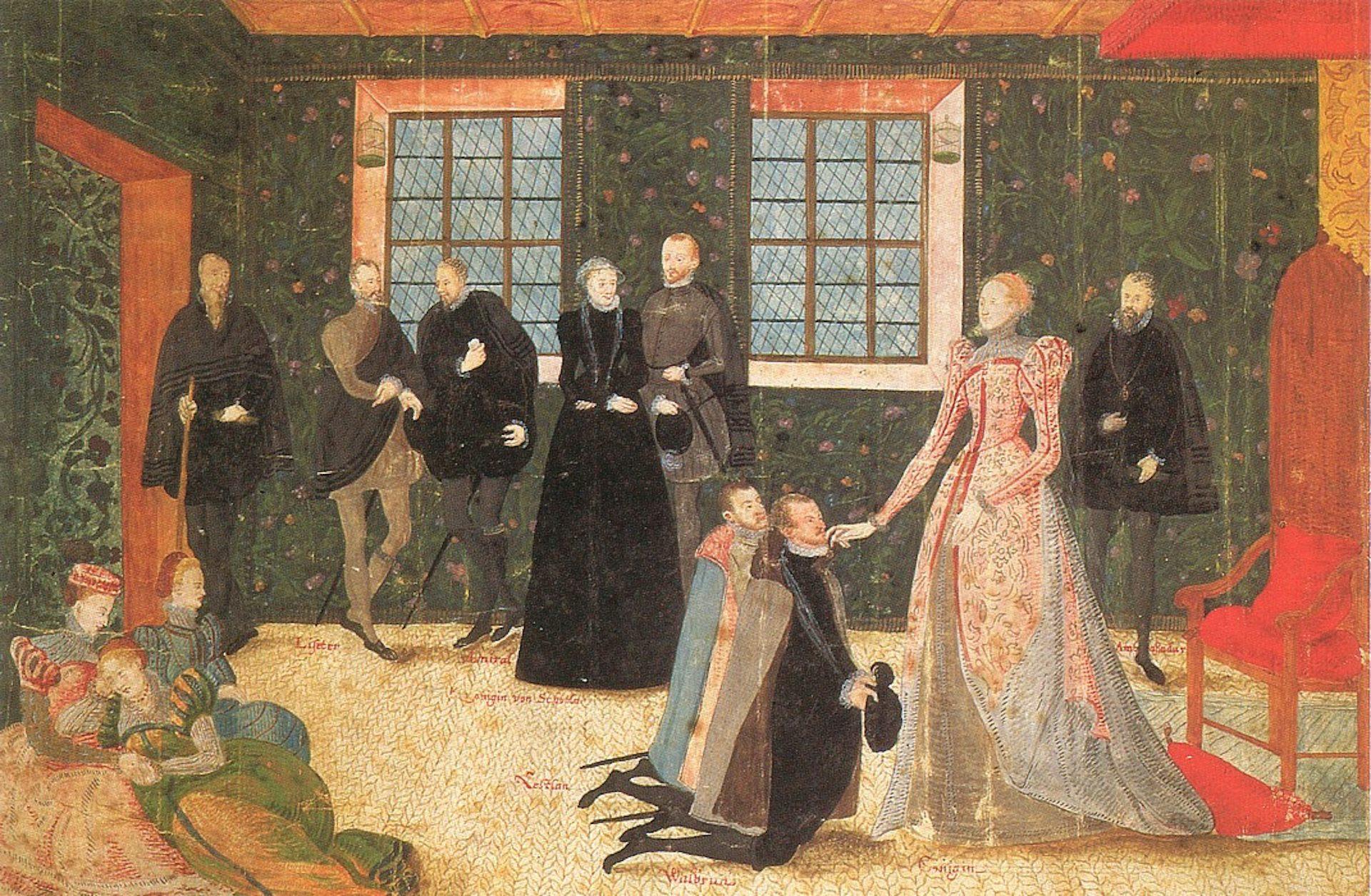

Of the 991 history exam questions set in 2023, 357 featured a named individual, but only 31 were women – and nine of those were references to Elizabeth I or her reign. In fact, Elizabeth I was the most frequently named woman across all exam content, including sources and mark schemes, appearing in 55 instances. The top 11 most referenced women included nine royal figures, six of whom were queens of England. Non-elite women and those from outside the UK and Europe were almost entirely absent.

A painting of Elizabeth I receiving Dutch ambassadors, attributed to Levina Teerlinc, a female artist at the Tudor court. Commons

This imbalance is not just about who gets named. It is about who gets seen, studied, remembered and valued. This skewed perspective also shapes the historical understanding of thousands of students across England, year on year.

In mark schemes, where the content needed to achieve marks is specified, women only appeared in possible answers for 22.8% of questions, compared to 83.1% for men. This matters because students are both taught and assessed based on these mark schemes. It's largely men who are presented as the“right” answer.

History exams also mention historians. Students are asked to respond to a historian's viewpoint, or expected to refer to historians in their answers. But out of 163 historians mentioned in exams, sources or mark schemes, only 22 were women. This is a problem: 47% of UK academic historians in 2023-24 were women, and female students often outnumber male students in history at every level. Despite the evident popularity of the subject for female students, they cannot see themselves in exam assessments.

The current assessment system in England not only fails to reflect the diversity of historical experience – it actively reinforces distorted, male-centric narratives. If we want students to learn inclusive, representative history, we must start with the exams that often shape what gets taught.

Equipped with a greater understanding of their own and each other's pasts and the skills to unpack diverse forms of evidence, students would be better informed to deal with conflicts and challenges as well as to reflect on other points of view.

History is not just about kings and wars. It's about people. And half of those people have been missing from the story for far too long.

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the

information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept

any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images,

videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information

contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright

issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Comments

No comment