Game Of Wool: Fair Isle Knitting Row Reveals Why Culture And Tradition Matter

Hosted by former Olympic diver and knitting convert Tom Daley, the show draws on the creative and technical skills of Di Gilpin and Shelia Greenwell – two of Scotland's most high-profile hand-knitting specialists as judges. Game of Wool was set to join the BBC's Great British Sewing Bee as a window onto the skills of amateur makers.

Yet, shortly after the first episode aired, the show found itself at the centre of a right old stooshie (a good Scottish word for a row). Advocates of Fair Isle knitting – the two-coloured stranded knitting technique and style with its origins in the eponymous island in Shetland – made their feelings known about the competitors' first task: to knit a Fair Isle tank top in just 12 hours.

Online discussion groups were scathing about the task itself and the workarounds required – chunky wool, large gauge needles – to knit such a garment in such a short space of time.

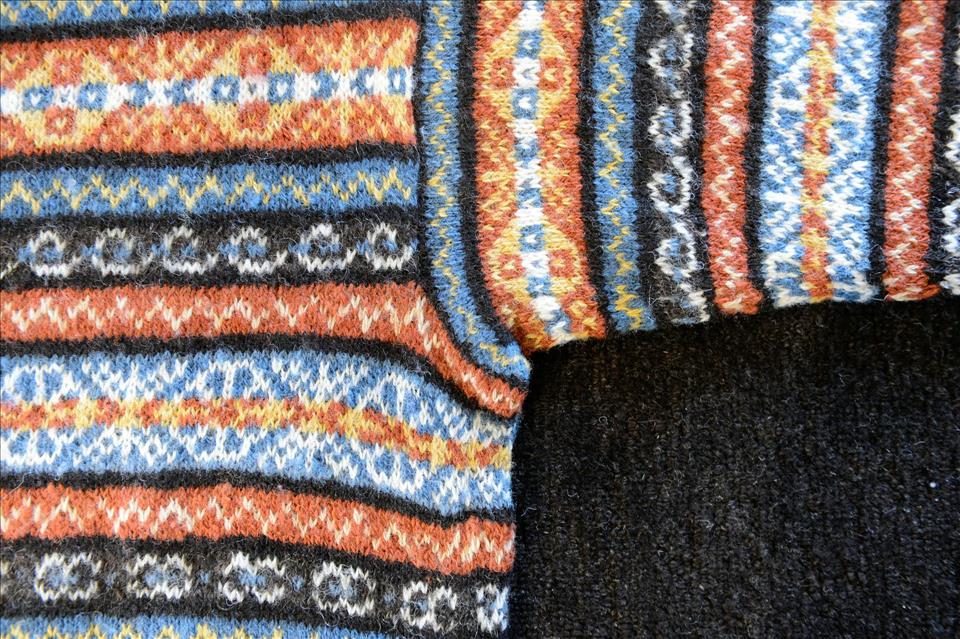

The distinctive Fair Isle technique and style, with rows of two-coloured stranded design containing large motifs such as the“OXO” pattern alternating with“peerie” (small) patterned rows, had been misleadingly represented, it was claimed.

So why did a competitive task on a game show engender such a spirited debate?

Fair Isle motifs have been deployed frequently outside Fair Isle and Shetland by top designers and knitwear manufacturers. The term Fair Isle is often used to denote almost any kind of multi-coloured knitwear. And yet while its origins are disputed, inhabitants of this small island and the larger archipelago of Shetland have been knitting Fair Isle garments for generations, developing individual colourways and motifs.

Traditionally Fair Isle garments were knitted using local wool from Shetland sheep, in natural harmonising colours such as black, moorit (brown) and fawn, or with yarn dyed indigo (blue), madder (red) and yellow.

It was in the 1920s that the“all-over” Fair Isle sweater (a garment knitted entirely in stranded colourwork) was popularised by the Prince of Wales, leading to high demand for the colourful styles far beyond their original location. By the 1930s Shetland knitters were experimenting with new patterns, colours and materials. And manufacturers in Shetland and elsewhere (including overseas), appropriated the hand-knitted designs for machine-knitted garments once machines capable of knitting Fair Isle patterns became available.

Culture, tradition and livelihoodsSo what is at stake for the knitting community in Shetland when a game show seemingly misappropriates a traditional craft practice? The issues for Shetland's contemporary knitting community concern the economic and cultural viability and authenticity of a craft with long and deep associations with this place.

Knitting here through the 19th and much of the 20th centuries, before the arrival of the oil industry, was an essential occupation for the majority of women. Whether knitting was conducted on needles or on a hand-operated knitting machine, it was poorly rewarded. Knitters still struggle to command fair prices for their garments in a marketplace dominated by mass-produced knitwear.

The modern knitting economy of the islands has a vibrant face, attracting thousands of textile tourists and knitting practitioners each year, not least during the annual Shetland Wool Week in October. But this craft needs protecting and maintaining if it is to survive.

Just one example of the vulnerability of this indigenous craft to the economic and cultural power of the fashion industry was the incorporation of independent knitwear designer-maker Mati Ventrillon's designs into Chanel's 2016 Métiers d'art collection without attribution.

A woman knitting a Fair Isle jumper in the Shetlands, circa 1979. Homer Sykes / Alamy

For Ventrillon, her designs, referencing historic local motifs and colours, are inseparable from Fair Isle the place, and her own life there as a knitter, crofter (a smallholding farmer in the Highlands) and member of a community of just 60 people.

In the wake of the furore that followed the Chanel show, she told the Business of Fashion:“All of these extra things – the things that I have to do, that I can't ignore – they're all part of the reason why these are luxury items. You're not only paying for the quality of the knitting, but for the hardship and the challenging lifestyle that is required to live and work off this island. And it has to be from this island because where else can Fair Isle knitwear come from, but Fair Isle?”

Ultimately Game of Wool has cast a valuable spotlight on a heritage craft under threat despite its global profile. SOK, the Shetland Organisation of Knitters, has been founded in the wake of this debate, to preserve, promote and protect Shetland's heritage knitting skills and culture.

Place matters. The craft product and the skills required to make a knitted garment embody a relationship between maker and place expressed through distinctiveness of materials, style, colourways, motifs and techniques. And although the power and reach of mass production has, in many cases, diluted this relationship, the original context of Fair Isle production remains important to both those who make it and those who wear it.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the

information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept

any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images,

videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information

contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright

issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Comments

No comment