New Cold War, New Cold Lines

Perhaps a new America is born with the virtual competition between two rare specimens of US politics, one moving to the right, the other to the left, leaving the center empty: President Donald Trump and Mamdani.

Is Mamdani the face of a new America, winning the hearts and minds of the nation and the world, or is he just a bellwether of a civil conflict that will rip the US apart and take it out of the international scene, leaving China in the limelight?

Will Mamdani move to the center and reach out to the many Americans unhappy with the current trends, or will he mirror MAGA's drive to crush his opponents?

Some feel America needs someone to confront President Trump because it's useless to try to find a middle ground with him. On the right, some share a parallel view. Will his divisive policy create more and broader fissures? Is the US on the brink of implosion or rebirth?

It matters a lot because the US is facing unprecedented challenges with China.

China's challengeUsing the term“Cold War” can help highlight the seriousness of the situation between the United States and China. The attrition is very intense, but it differs from the first Cold War.

The initial Cold War began before World War II, through a period of purely political disputes that didn't involve state-to-state controversies. Even before World War II, there were already early tensions between the liberal capitalist world and the Communist world.

It was a struggle between communism and capitalism, rooted deeply in Western culture. Communism originated in the 19th century, a century before the first Cold War.

When the Cold War started, there was already a clear division: you on one side, me on the other; you support the market, I oppose it; I believe in a thoroughly planned system where a group or a single person makes all the decisions; on the other side, you are for a democratic, liberal system.

Today, the situation has changed. The two economic systems-one centered on China and the other on America-are interconnected. It's clear in recent trade negotiations.

On one side, America imposed tariffs not only on China but also on other countries it believed were exploiting the American market. On the other side, China imposed export restrictions on rare earth elements (REE), impacting not just America but the global economy.

This economic integration, which has lasted for the past 40 years, is about to unravel. However, the appeal of that integration led many to believe that, once this dispute-a commercial one, after all-was resolved, everything could return to the way things were before.

In reality, the dispute is not simply commercial. There is a commercial issue-European or Japanese surpluses compared those of the United States. This is mainly something that can be solved with trade tools: remove this subsidy here, open this market sector there, import more of this and less of that.

The Chinese issue is more complex. Around the late 1990s-about 25 years ago-then-Chinese Premier Zhu Rongji aimed to reform the Chinese economy and achieve full convertibility of the RMB. He reformed the financial system and sought to liberalize the Chinese currency fully.

However, for many reasons, this never materialized. The Chinese market and its financial system have remained largely separate from the broader commercial economy, not only in the United States but also worldwide, where countries operate in markets with freely floating currencies, thereby subjecting them to exchange-rate fluctuations.

Moreover, over the past 20 years, China has built a highly complex and unwieldy economic system that is neither solely market-based nor purely administrative, but a mix of both. It's not the centralized planning system of the old Soviet economy. Still, it isn't like the economies with a strong presence of state-controlled enterprises that dominate the market, such as Japan, Korea, Germany, or Italy.

In China, it is not the companies but the local governments-cities, provinces and sometimes districts-that play a dominant and shaping role in both the market and finance. Lizzie Lee provides a very accurate description and analysis of the environment (see here ).

These government entities then interact with each other, with businesses, and with the central government.

A chaotic planInitially, this system may appear more organized than the chaos and constant threat of market instability in capitalist countries. It is also more efficient than the endemic inefficiency of a planned economy. But ultimately, over time, it proved more chaotic than the apparent disorder of a free market and perhaps even more inefficient (with different kinds of inefficiencies) than a planned economy.

It's a mixed bag, not simply one thing. In theory, China should be able to address this challenge. But that would mean dealing with structural and institutional problems it doesn't seem willing to confront.

Adding to this-here it becomes a dangerous stew-are ideological controversies (that the Chinese are communists); geopolitical disputes (Chinese ambitions regarding Taiwan, the South China Sea, or parts of the Himalayas); mutual suspicions (the Chinese fear that America's ultimate goal is to establish a kind of total, global dominance to eliminate China).

Latest stories

Space terrorism no longer the realm of science fiction

Dick Cheney's vision of presidential power culminates in Trump

Markets quake as investors put profit over promise from AI

As a result, a new nationalism emerges, and these factors reinforce one another. On the one hand, they isolate China not only from America but also from the rest of the world; on the other hand, the new confrontation rose amid elements of potential cooperation. Then it's not easy to determine how to handle it.

Trump, during his first term, tried to address the issue by breaking it down: focus on the trade dispute and see if it can be resolved at least partially. Simplify the challenge. The idea was reasonable in principle, but for many reasons, it didn't succeed.

Then came the complication of the war between Russia and Ukraine, followed by the war in Gaza-real, intense conflicts like those during the first Cold War. In these two hot conflicts, the leading players took opposing sides: the US supported Ukraine, while China backed Russia; China also interacted with Hamas and obviously supports Iran, whereas America stood on the opposite side.

With all these elements, we face a situation that is very new and hard to explain or understand. What is happening now, also thanks to Trump's disorderly and perhaps unavoidable efforts, is an attempt to clarify. Maybe we are reaching a clarification, but not a short-term solution. Instead, it is for a long-term clash/friction.

Therefore, we may have to prepare for a progressive increase in tension, but hopefully, controlled. Here, there are many complications between long-term goals and short-term deadlines.

The first issue concerns REE. Optimistic Americans believe it may be possible to produce REEs within a few years, thereby breaking free from the Chinese yoke. Others think it could take 10, 15 or even 20 years. The yoke remains until this global strategic dependence on Chinese rare earths is broken.

On the other hand, the West is in the middle of a crisis, and the Chinese are energized by it. It's like what happened to the Communists in the 1950s, who saw the crisis in Western countries and thought,“Here is proof capitalism is collapsing.” It turned out differently.

Two WestsThe issue is what is in crisis and what is not.

The crisis of the West? There are two Wests that we often confuse but should not. One is a West directly descended from the legacy of the Roman Empire, which split into three great empires: the Holy Roman Empire, the Russian Empire and the Ottoman Empire (see here ).

These three empires continued to dominate the Western world and the Mediterranean basin, expanding in all directions-east, west, south, and north-until 1919, the end of World War I. At that point, all three empires collapsed simultaneously. Conversely, over the centuries from the 17th and 18th centuries, and then more rapidly in the 19th century, a second“West” emerged outside the physical West of the Mediterranean.

It expanded naturally. The first region of expansion was the American continent. Then Asia followed, with countries like Japan, Korea and India. Today, we categorize them as“Western,” even though they are neither geographically Western nor part of the Western-originated“civilization”-because they have a different history. However, they embraced the capitalist and liberal world-the new set of market-oriented rules originating in the West-without being constrained by Western physical provenance.

This second wave of Western expansion worldwide was so widespread that even China eventually adopted some Western elements, including communism (a Western concept) and Deng's market reforms.

This second West should not fear itself or its history because 1) the old West is gone, and 2) this second West may have caused great disasters, but has also achieved unprecedented results. For the first time in human history, in a century and a half, average human lifespans have tripled. The planet's population has increased tenfold; quality of life has risen exponentially.

Unlike other contemporary socialists, even Marx, the most famous critic of capitalism, didn't criticize capitalism on“moral grounds” but for economic reasons-unequal distribution of income.

Smith and Ricardo explained the mechanics of the market and the structure of cost and price; Marx argued that there was another element, labor cost, that was not adequately explained and thus not adequately compensated, but called the buildup of wealth leading to capitalism's“primitive accumulation.”

There were no phones, telecommunications, heating or artificial light. For thousands of years, we essentially kept warm by putting our hands near the fire. Today we fly-something that never happened before-go to space and are relatively independent from the forces of nature.

These are unprecedented developments; moreover, despite some claims that technological progress is slowing down, as philosopher-billionaire Peter Thiel argued (see here ), the benefits of this progress are spreading worldwide. They are no longer limited to a few privileged countries.

For the first time, the world is globalized, but the center is no longer Europe and the Atlantic route; it's Asia and the Pacific route. This shift began in the 1980s, when Thiel said there was no change left. The fact that the lives of some Americans don't change doesn't mean the world isn't changing.

Then, what is there to be ashamed of for having improved the lives of so many people? Many who complain today probably would have died at birth just a century ago.

Given these undeniable results of Western tradition, culture can act as a foundation for exchange and confrontation with China, which has gained from this substantial push toward Westernization.

Therefore, it could be a way to speak to China and to see if there can be a real space for dialogue.

The China turnPerhaps there's a historical cultural oversight on China's part. Between 2004 and 2009, Beijing became disillusioned with democracy and the free market. In 2004–2005, the American intervention in Iraq fell apart, and America failed to export democracy to Iraq successfully; in 2008–2009, the financial crisis revealed the fragility and massive flaws of the American financial system.

These two huge failures convinced China that it was better to keep everything under control and no longer try to follow the American example. It was about both the political system (where some considered moving toward democratization, which was a possibility at the time) and market liberalization.

The Chinese logic makes sense. It's practical: it doesn't work, I don't use it. But maybe the Chinese overlooked a longer-term perspective. Sure, America was wrong in its intervention in Iraq and in how it handled the financial crisis.

However, there is a long-term aspect: the lasting value and resilience of liberal systems. It is true that if a liberal system loses focus on the long run, it can act as if it is intoxicated. But historically, liberal systems have consistently managed to control and steer both the short- and long-term, even despite many short-term mistakes.

Take the Napoleonic Wars, for example. Napoleon had conquered all of Europe; he had a mighty military and political force, yet England, although smaller but with a more flexible financial system, managed to defeat him.

The same happened with Venice, which, for centuries, was a small power that controlled trade through a clever financial system and a republic of merchant-warriors who gathered to discuss the future of the Republic. Similarly, Genoa managed to hold onto control and even push back the Ottoman advance.

Liberal systems have significant strength because they rely on voluntary consent through elections and free funding, which can motivate individuals to contribute in ways that autocratic systems led by an emperor or an extremely intelligent, enlightened sovereign may not.

An autocratic sovereign usually cannot count on the voluntary contributions of all citizens who do not see themselves as stakeholders in their government, nor do they feel like stakeholders. No matter how loyal subjects are, they are different from stakeholders.

Today, America faces a similar challenge: confronted with those who doubt the value of democracy, it has a wide range of tools - both long- and short-term - to combat all authoritarian systems. If America stops believing in its own system and democracy and instead tries to become something else-a fully authoritarian system-then a fundamental obstacle arises.

If a newly autocratic United States were to confront another authoritarian system, such as China, with over 2,000 years of experience of authoritarian rule, then the US, with less experience, could also be less efficient.

But if America does not stop believing in itself, then China could face difficulties. Alternatively, if America loses focus, China might succeed. Perhaps the most essential part of Michael Pillsbury's book on China,“The Hundred-Year Marathon”, is the final chapter, where he offers a series of policy recommendations for the US to counter China. His recommendations, ten years after the book's initial publication, have yet to be fully implemented.

Moreover, if China sees that America does not stop believing in itself, if America renews itself through democracy, and if the liberal system revitalizes and expands its influence and power, then, since the Chinese are very pragmatic, perhaps they would start to reconsider how to confront America.

The main issue for China right now is its inability to boost domestic consumption. Beijing is unable to do this because the ordinary Chinese are cautious and apprehensive about their uncertain future.

Sign up for one of our free newsletters

-

The Daily Report

Start your day right with Asia Times' top stories

AT Weekly Report

A weekly roundup of Asia Times' most-read stories

They are not panicked because they see chaos and confusion elsewhere in the world, so they follow the government, which provides them security. At the same time, they are less optimistic about the future, which leads to less spending and investment, and they are much less proactive than they were over the past 40 years.

This lack of activity and optimism among Chinese consumers and entrepreneurs is what is holding the entire country back, and perhaps it can only change if China revises its political and social system. It does not do so because it fears that importing the American system after the failures in Iraq and other democracy-exporting efforts would unravel its whole system.

There are very delicate elements, but it might begin with a renewed American confidence. If America doesn't believe in itself, how can others believe it can ever win?

A coda: population and trends

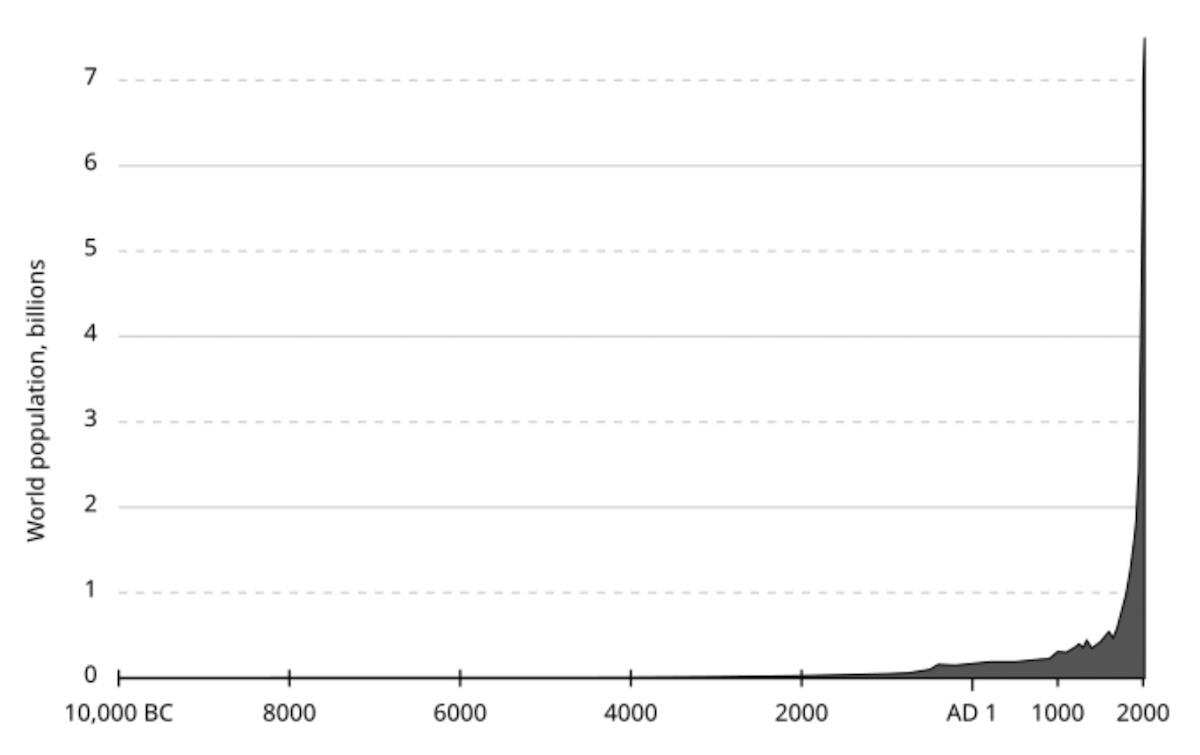

The graph above shows that for 6,000 to 7,000 years after the start of the agricultural revolution and the end of the ice age, the population remained stable. It began to grow from the 4th millennium BC, with the dawn of civilizations, increasing from 7 to 60 million people by 750 BC.

It experienced its first surge at that time, coinciding with the beginning of the Axial Age and the spread of the world's first cities. Over the next 2500 years, growth was slow, reaching 600 million by 1600, the start of the liberal revolution.

It added 200 million over the next two centuries, and then, in the last 150 years, with the surge of modernization, the population grew tenfold. It now shows signs of stabilizing globally and declining in the most developed countries.

The main reason is that children are no longer a driver of economic success, as they have been throughout history, but are now simply a“hobby”-a pleasure rooted in ancestral instincts.

Children no longer need to care for their parents, and workers are no longer necessary to produce goods. AI and robots take their place, and better medical care enables people to live longer and have more active lives. As a result, a larger population isn't needed, except to increase consumption.

Or if war breaks out. The massacres in Ukraine remind us that conflicts still involve massive waste of steel and blood. Therefore, countries still need surplus populations, an excess of mad young people willing to go to kill or be killed. But short of an earth-shattering nuclear war, the global population likely won't face a shock.

Instead, it could first stabilize and then decline worldwide, delegating more tasks to machines, as Marx first predicted in his third book of Capital. But the key question is: how will this transformation be governed? Through a process of increasing liberal modernization or through authoritarian regimes?

Here, Thiel could be vindicated. It's not true that innovation has slowed down; it's spreading globally (no longer limited to a few wealthy places) and taking a new direction (telecom, AI, space). However, it could be different if autocracies come out on top. They focus on stability, not racing toward a different future.

Unless different autocracies start competing with each other, it would be a new era of warring states, as four Chinese thinkers - Li Xiaoning, Qiao Liang, Wang Jian, and Wang Xiangsui - predicted 25 years ago. The book“Xin Zhanguo Shidai” (the new period of the Warring States) refers to the 7th-3rd centuries BC age, when a few states emerged from the previous chaotic era, fought each other and were eventually unified by the First Emperor.

The book was first presented in 2004 at the Italian Cultural Center in Beijing, where I was director at the time.

This article was born out of a conversation with Giuseppe Rippa, whom I thank. It first appeared on Appia Institute and is republished with permission.

Sign up here to comment on Asia Times stories Or Sign in to an existing accounThank you for registering!

An account was already registered with this email. Please check your inbox for an authentication link.

-

Click to share on X (Opens in new window)

Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

LinkedI

Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

Faceboo

Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

WhatsAp

Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

Reddi

Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

Emai

Click to print (Opens in new window)

Prin

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the

information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept

any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images,

videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information

contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright

issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Comments

No comment