US-Based Construction Of South Korea's N-Sub: It's Complicated

Although approval has reportedly been granted by the United States for South Korea to develop a nuclear-powered submarine, the stipulation that construction occur at a shipyard in the United States marks a significant deviation from South Korea's longstanding pursuit of independent design, fuel acquisition and domestic construction capacity.

South Korea's strategic planning in recent years has been based on the view that true national defense autonomy requires full control over production and sustainment in key military programs. The new submarine proposal therefore raises questions in Seoul not only about immediate costs but about long-term strategic positioning.

The strategic, diplomatic, industrial, and regional implications of this proposed arrangement are expected to be significant not only for South Korean defense and security dynamics but for the entire Indo-Pacific region.

The timing is particularly important. Northeast Asia is experiencing rapid military modernization, increased great power competition and rising tensions in critical maritime zones.

South Korea's infrastructure constraints, regulatory hurdles nuclear fuel policy issues and shifts in regional security alignments are expected to play a major role in fulfilling South Korea's ambitions to possess nuclear-powered submarines and build a self-reliant armed force capable of playing a more prominent role in maritime security in the Indo-Pacific region.

Policy planners in Seoul have long argued that South Korea's modern navy must be able to operate far beyond coastal waters, particularly given the nation's trade dependencies and exposure to maritime chokepoints.

South Korea has long considered the acquisition of nuclear-powered submarines a critical national security objective, driven by the need for extended underwater endurance and enhanced deterrence capabilities.

The primary barrier to realizing this objective has been securing enriched uranium fuel suitable for naval propulsion. During a recent bilateral summit, President Lee requested that the United States provide a decisive position on enriched uranium supply, asserting that all other conditions for the program were already in place.

However, the response from President Trump was not expected by many South Korean planners and policymakers. Trump was willing to allow South Korea to operate its first nuclear submarine – provided that it be built in the United States. This conditional approval, tied to construction at a shipyard located in Philadelphia, took the South Koreans by surprise.

Latest stories

A battlefield report: Neither side is winning US-China trade war

Singles' Day, a $150B holiday in China, will catch on in the US

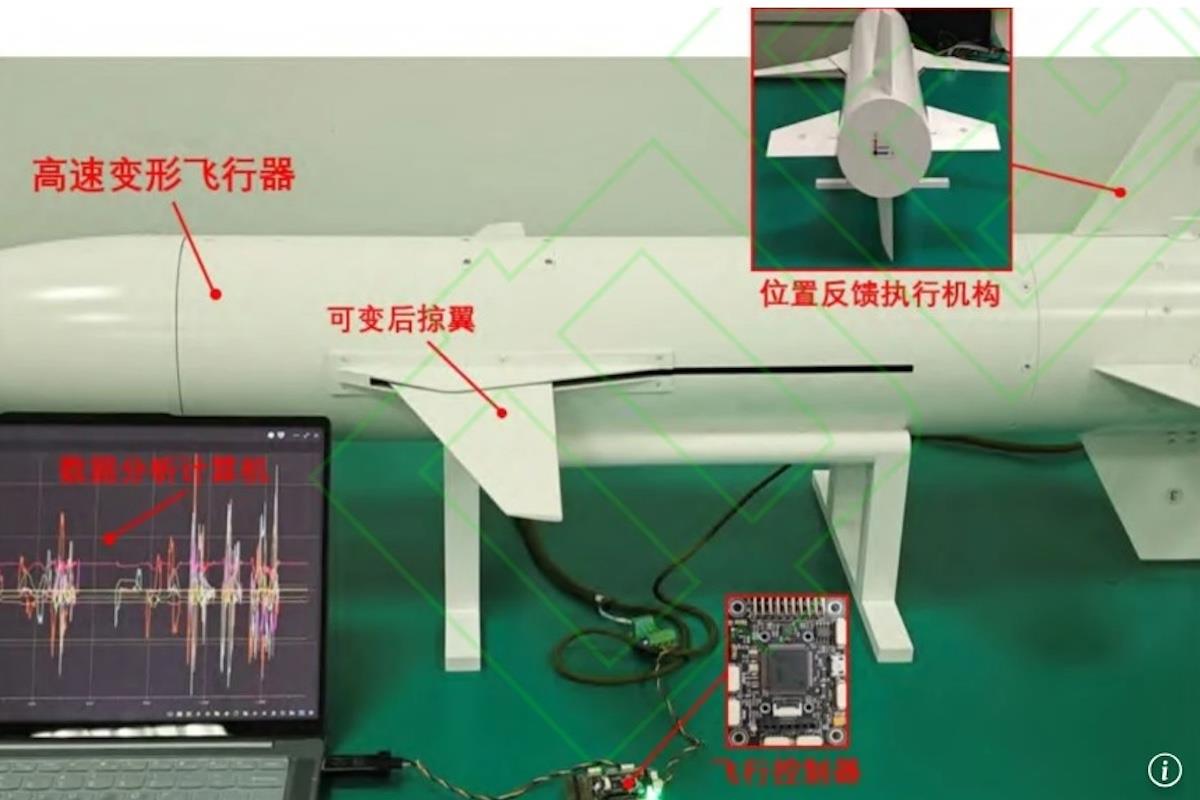

China's latest hypersonic missile morphs at Mach 5

The shipyard in question is currently owned by a South Korean defense corporation but lacks facilities for submarine construction. For many in Seoul, this condition suggested that while Washington was granting approval in principle, it was simultaneously aiming to direct substantial economic and industrial benefits back to the United States.

Thus, while the proposal was publicly framed by US leadership as strengthening South Korea's naval capabilities, it was also seen as part of a broader agenda to revitalize US shipbuilding capacity for national security purposes. As a result, many viewed the proposal as not fully aligned with South Korea's long-established plan to build nuclear submarines at domestic shipyards.

This is perplexing South Korean defense policymakers regarding how they should proceed from here. They may not have easy choices to make going forward, as this proposal by Trump impacts South Korea's aspiration to build a self-reliant defense force at multiple levels.

Multiple constraintsAlthough South Koreans in general were pleased to receive approval from the United States to pursue nuclear-powered submarines, the proposal introduces substantial industrial and cost-related complexities.

The Philadelphia shipyard where President Trump has proposed that South Korea build its new submarine currently possesses infrastructure for commercial vessels and large warships, but it was never designed for the specialized manufacturing of advanced nuclear submarines. Establishing the necessary facilities would require not only physical restructuring but recruitment and training of a specialized workforce, integration of nuclear safety protocols, and close regulatory oversight.

Analysts within the South Korean defense sector indicate that establishing an adequate submarine production line would require at least three to five years of preparation. Given the rapidly changing balance of power in the Indo-Pacific, this new schedule may not align well with South Korea's maritime policy planning.

Furthermore, estimates suggest that constructing the submarine in the United States could cost three to four times more than building it domestically due to higher labor costs, logistical inefficiencies and regulatory compliance burdens. Here again, given South Korea's contracting economy, this proposal may not find strong support within the political establishment.

Beyond time and cost concerns, the precise meaning of the US approval remains ambiguous. It remains unclear whether the approval allows South Korea to develop the submarine's overall design while conducting final assembly in the United States – an arrangement without historical precedent and viewed as impractical.

If the proposal involves the transfer of US submarine reactor technology, it intersects with highly restrictive export control frameworks. This may require revising the existing Korea–US Nuclear Agreement, which primarily governs civilian nuclear power and does not address naval propulsion fuel.

The current framework prohibits South Korea from producing even low-enriched uranium and bans reprocessing of spent fuel, preventing completion of a full nuclear fuel cycle despite advanced domestic capabilities. Such limitations further complicate the nuclear regulatory environment in the region.

Under existing international arms control regulations, any export or transfer of nuclear submarine-related technology requires coordinated review by multiple US federal agencies and, in many cases, explicit Congressional authorization. This process is neither guaranteed nor rapid.

Additionally, such cooperation would place South Korea's submarine development under extensive US oversight, potentially constraining Korean aspirations for strategic autonomy.

Considering intensifying political polarization within South Korea, it may not be easy for President Lee Jae Myung to obtain necessary political support for this proposal, especially among groups already dissatisfied with trade arrangements perceived as burdensome on the Korean economy.

Under this proposal, many feel, even if South Korea is permitted to operate nuclear-powered submarines its autonomy in managing nuclear fuel production, storage, and long-term fuel cycle development will remain restricted.

This outcome is likely to disappoint those in South Korea who had hoped, in light of North Korea's nuclear advancements, to expand national authority over nuclear technology and fuel production.

Many in South Korea had anticipated that upgrading the existing civilian nuclear cooperation agreement would allow for greater flexibility in nuclear fuel production and management. Their expectations now appear to be undermined. Although limited adjustments may be negotiated to accommodate naval propulsion fuel, the fundamental restrictions on South Korea's nuclear sovereignty are likely to remain unchanged under this new proposal.

This was not what South Koreans were aiming for with this nuclear-propelled submarine project.

Sign up for one of our free newsletters

-

The Daily Report

Start your day right with Asia Times' top stories

AT Weekly Report

A weekly roundup of Asia Times' most-read stories

The introduction of South Korean nuclear-powered submarines, particularly with US industrial involvement, is likely to have significant implications for Northeast Asian security.

China, currently engaged in strategic competition with the United States, is expected to strongly oppose any enhancement of South Korean undersea nuclear propulsion capability, viewing it as aligned with US maritime containment strategies. China's close partners, Russia and North Korea, are also expected to react negatively and may take countermeasures.

However, countries such as Japan and India, which have advocated for a more active South Korean naval role in the South China Sea and Indian Ocean, are expected to view this development more positively.

In recent years, Japan has also signaled interest in acquiring nuclear-powered submarines. With policy discussions in Tokyo emphasizing next-generation propulsion and strengthened maritime defense capability, Japan may not be far from pursuing similar developments. South Korea's move could therefore accelerate parallel Japanese initiatives.

This dynamic, however, could trigger a new regional naval propulsion competition, reshaping the maritime balance of power in the Indo-Pacific. Indian defense policymakers are expected to watch these developments very closely, as any shift in submarine deployment and capability will influence maritime balance in the Indian Ocean region.

This also has the potential to further strengthen India–South Korea maritime cooperation in the Indian Ocean and the South China Sea across multiple domains of naval warfare.

The ultimate trajectory of the new US proposal to authorize South Korea's nuclear-powered submarine acquisition while requiring construction at a US shipyard will depend on negotiations concerning nuclear fuel supply, regulatory approvals, and regional security responses.

As the proposal carries long-term implications for defense sovereignty, alliance management and the evolving maritime balance of power in Northeast Asia, strategic thinkers and planners in the region are expected to keep a close eye on the project as it moves forward.

Sign up here to comment on Asia Times stories Or Sign in to an existing accounThank you for registering!

An account was already registered with this email. Please check your inbox for an authentication link.

-

Click to share on X (Opens in new window)

Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

LinkedI

Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

Faceboo

Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

WhatsAp

Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

Reddi

Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

Emai

Click to print (Opens in new window)

Prin

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the

information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept

any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images,

videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information

contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright

issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Comments

No comment