How Hungary Understands Russia's Ukraine Policy

The choice of venue was not accidental, as Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban maintains good personal relations with both heads of state. This fact highlights that from Central Europe, directly bordering Ukraine, we judge Russia's behavior differently than the European elite sees it.

Therefore, we will now examine the reasons for the Russians' tough behavior from the Hungarian perspective.

Russia has dug in its heels and insists that in the future, no NATO troops - not even in a peacekeeping capacity - may be stationed in Ukraine. According to the Kremlin, this would pose a potential threat to its security.

Another demand from Moscow is that the entire territory of Donbas - including areas not inhabited by Russians - should be incorporated into Russia. This, they argue, is for geostrategic reasons.

Thirdly, the Kremlin refuses to accept an unconditional ceasefire, fearing that Ukraine would use it to gain time for military preparations. Any truce, it says, would only be possible if Russia received guarantees that the fighting would not resume.

US policymakers do not understand Moscow's behavior. In this article, we attempt to explain the factors behind Russian thinking. Washington fails to grasp Moscow's actions because every nation's political mindset - including America's - is rooted in its history.

The United States is a country of immigrants, with many highly qualified citizens of Russian descent, which makes it all the more puzzling that such people are rarely given the opportunity to influence U.S. policy. Russians, after all, cannot be understood from the comfort of an air-conditioned office in front of a computer screen.

Through a few selected examples, we will outline the historical facts that form the foundation of Russia's current way of thinking. We will focus only on Western Europe, since that region is most relevant in the context of the war in Ukraine.

In 1612, the Polish–Lithuanian Union attacked Russia, and in 1741 Sweden did the same. Later, in 1756, the Tsarist Empire became involved in several military conflicts with the Hohenzollern Prussian dynasty, which would later rule the unified German Empire.

Russia also fought several wars along the eastern edges of Western Europe - most notably the Napoleonic invasion of 1812, during which the French army even captured Moscow. Jumping ahead, in 1941, Nazi Germany once again launched an attack against Russia.

Latest stories

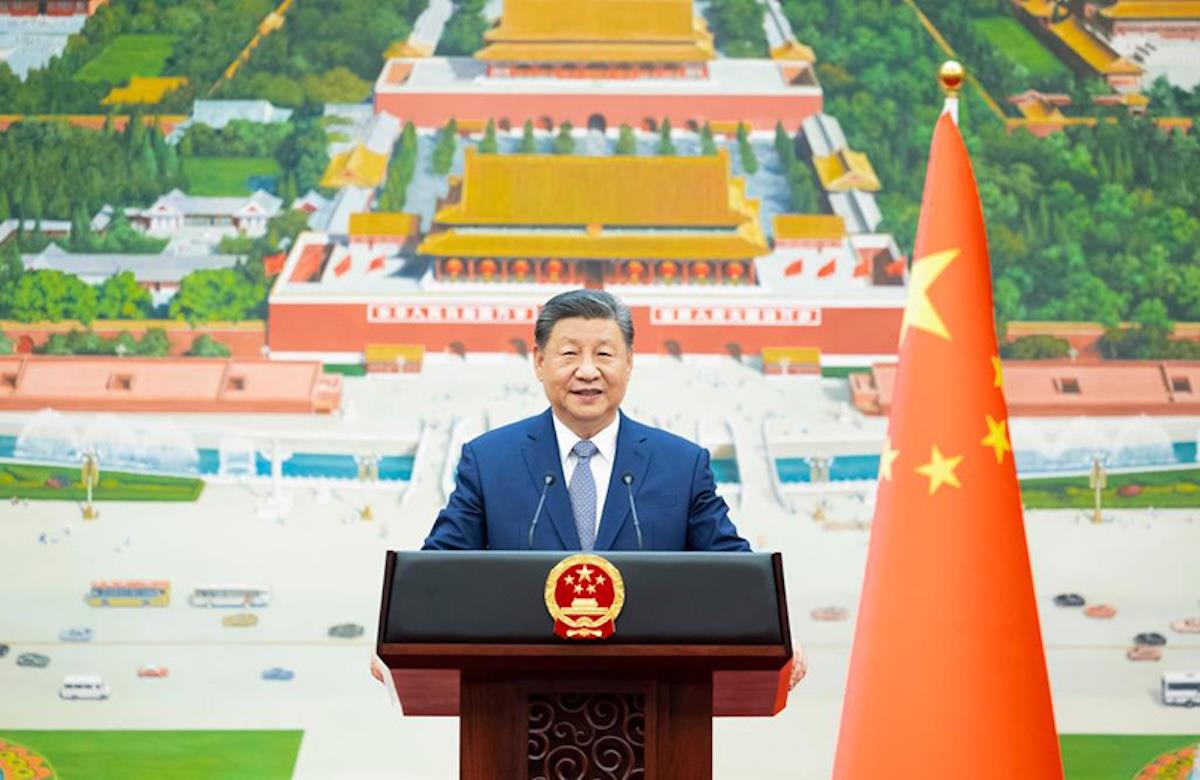

China's hard-won strategic lead over the US: Can Xi make it last?

Military goals behind push for small civilian nuclear reactors

Allied shipbuilding is Asia's next strategic supply chain

Thus, in every such case, Russia faced a military threat coming from the West. After each of these wars, Russia managed to expand slightly westward - perhaps not immediately, but in the long run, the outcome usually favored the Russians.

All the attacks against Russia were motivated by the empire's immense wealth in mineral resources and vast tracts of fertile farmland - assets the Western powers, driven by a colonial mindset, sought to seize.

Consider this: during World War II, Nazi Germany plundered a significant portion of its food supplies from Russia and obtained much of its oil from there as well.

In every instance, Western European aggressors assumed that Russia was technologically backward, economically underdeveloped, unable to solve logistical problems due to its vast distances, and lacking advanced Western technology - and therefore, that it could be defeated.

When it comes to the current war in Ukraine, the global West - perhaps with the exception of the United States - is once again applying the same assumptions toward Russia. Every one of these attempts throughout history has failed.

To better understand today's situation, we cannot avoid mentioning Tsar Peter the Great, who ruled from 1682 to 1721. Peter was the ruler who began Russia's modernization. As Henry Kissinger once said,“Russia has been an integral part of Europe for three hundred years.”

The tsar not only modernized his country but also left behind a lasting - in modern terms, geostrategic - doctrine for his successors. According to this doctrine, Russia will only be secure when all the countries along its borders are friendly - that is, under Russian influence.

Let's look at a political map from about three and a half decades ago. Along the eastern borders of the then–Soviet Union, Moscow had its satellite states: Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, and Romania. (Bulgaria and East Germany also belonged to the communist bloc, but they did not border the USSR.) Stalin formulated this principle during World War II:“The great power that occupies a portion of Europe will bring along its own social system.”

As we can see, territorial security - keeping potential enemies far from its borders - has always been a top priority for Moscow. This is why Russia refuses to allow NATO troops to be stationed in Ukraine under any circumstances.

But what does this have to do with the annexation of all of Donbas?

Donbas and the adjacent southern and northeastern regions provide Russia with a land connection to the Crimean Peninsula. Crimea is of immense strategic importance to Moscow, not least because Sevastopol is the headquarters of the Russian Black Sea Fleet.

Although the current focus is on Donbas, it's hard to imagine - given the importance of that land corridor - that Moscow would be willing to give up the surrounding territories. As for Crimea, the Kremlin refuses even to discuss its status.

We now arrive at the most sensitive question: why is Russia so distrustful of the global West?

In early December 1989, on the eve of the Eastern European regime changes, US President George H. W. Bush and Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev met in Malta. According to the Russian version, they agreed that the Soviet Union would not interfere in the Eastern European transitions, while America, in return, would refrain from extending NATO's influence eastward.

Bush and Gorbachev meet in Malta

Washington later claimed that no such firm promise had been made. No official transcript of the meeting was ever produced. However, considering Peter the Great's doctrine, it's hard to imagine that Gorbachev would have left the negotiating table without receiving some kind of assurance against NATO's eastward expansion. Whatever the truth, Moscow feels deceived.

Today, nearly all Eastern European countries - and even the three former Soviet Baltic republics, Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia - are members of NATO.

Russia's mistrust of the West deepened further in February 2014, when the then–US administration and the European Union helped orchestrate a coup against the legally elected Ukrainian president, Viktor Yanukovych, who fled to Russia.

The background to this unconstitutional takeover was that Yanukovych, at the last moment, refused to sign the EU–Ukraine Association Agreement and instead turned toward Moscow.

Viktor Yanukovych and Vladimir Putin

Sign up for one of our free newsletters

-

The Daily Report

Start your day right with Asia Times' top stories

AT Weekly Report

A weekly roundup of Asia Times' most-read stories

From that point on, the Western powers began preparing Ukraine for war against Russia. Former German Chancellor Angela Merkel later admitted this herself in a December 2022 interview with the German weekly Die Zeit, stating that the Minsk negotiations - aimed at ending the war in Donbas and involving Germany, France, Russia, and Ukraine - merely served to buy time for Ukraine to strengthen and prepare itself.

To this, Putin remarked,“We made the right decision.” The Russian president meant that by launching the attack, they had preempted Ukraine's full military readiness.

The next stage in Russia's loss of trust toward the West came in Istanbul at the end of March 2022. There, Russian and Ukrainian negotiators reached an agreement on a ceasefire and even initialed the document. But in early April, British Prime Minister Boris Johnson arrived in Kyiv and ordered Zelensky to continue the war.

What is the global West's goal in waging war against Russia?

A year ago, Kaja Kallas - then Prime Minister of Estonia and now the European Union's High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy - gave a clear answer. She stated unequivocally that the goal is to break up Russia into smaller states, which, in her view, would even have certain advantages.

Therefore, anyone who sits down to negotiate with the Russians must have a thorough understanding of all the above. No agreement will be reached until the Kremlin receives firm guarantees that its territory is secure.

Nor should anyone expect Moscow to end the war because of possible severe financial hardship. The endurance capacity of Russian society is far greater than wishful Western thinking would like to believe.

This article first appeared on Stephen Bryen's Weapons and Strategy Substack. Read the original article authored by Feher Peter here.

Sign up here to comment on Asia Times stories Or Sign in to an existing accounThank you for registering!

An account was already registered with this email. Please check your inbox for an authentication link.

-

Click to share on X (Opens in new window)

Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

LinkedI

Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

Faceboo

Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

WhatsAp

Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

Reddi

Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

Emai

Click to print (Opens in new window)

Prin

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the

information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept

any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images,

videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information

contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright

issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Comments

No comment