Sudanese In Jordan... At The Mercy Of Legal Restrictions And Labor Exploitation

Amina does everything she can to work whenever opportunities arise, either through her acquaintances or by doing household work requested by families in the neighborhood, to cover her family's needs and her younger child's anemia medication. However, the informal nature of her work makes her vulnerable to exploitation, as some withhold her wages or deduct from them, since she works without any legal protection. She laments:“I work a full day, and in the end, either they don't pay anything, or they give me goods and say there's no money, or they humiliate us just to get what is rightfully ours.”

Her husband, Rasheed, works day-to-day in construction workshops and also faces rights violations, sometimes receiving only a small portion of his promised wages, and other times none at all, resulting in accumulated rent arrears and debts.

On one occasion, Rasheed (28) worked in a construction site for 15 days, with an agreement of 15 JOD per day. Yet, he was paid only 30 JOD. Despite repeated promises from his employer to pay the remaining amount later, the employer stopped responding entirely, leaving Rasheed forced to accept the reality.

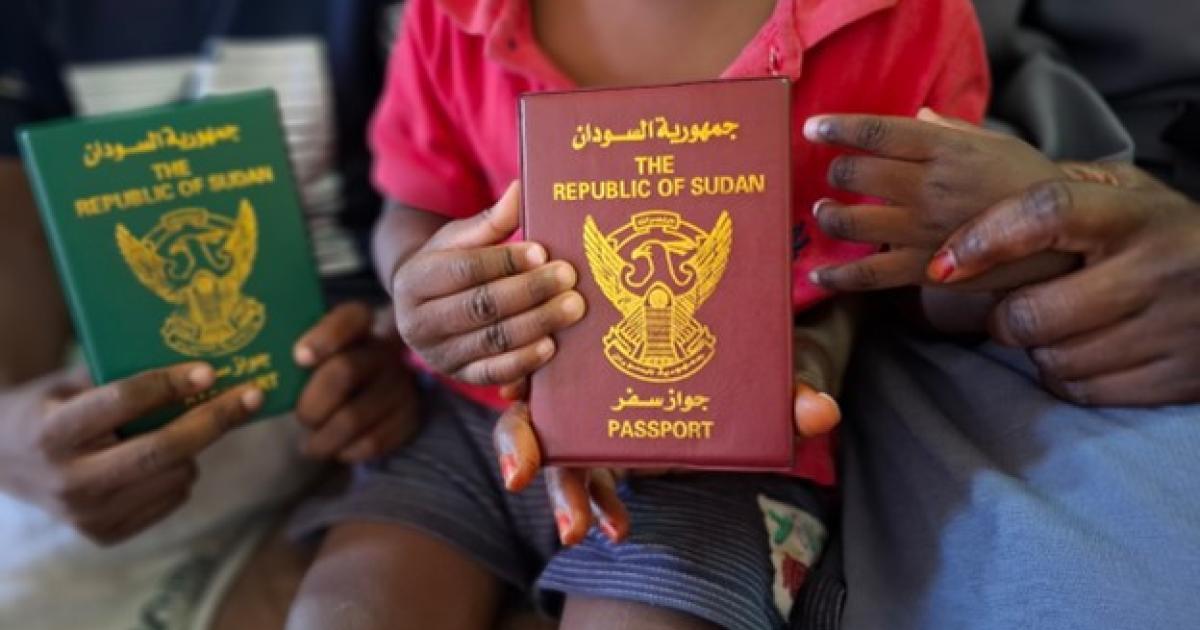

According to the latest statistics from the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR), the number of Sudanese refugees in Jordan is approximately 4,467. In the absence of precise official figures on asylum seekers, those holding refugee certificates face a difficult reality: they are denied a fundamental right-the right to work. This deprivation makes obtaining official work permits difficult, pushing them into the informal market as the only option to earn a living and support their families, exposing them to exploitation in workplaces lacking legal protection and social justice.

A Single Option and Widespread Violations

Most Sudanese in Jordan work in agriculture, construction, daily labor, and service sectors, according to Tamkeen Association for Legal Aid and Human Rights. The association documented 51 labor complaints by Sudanese in the Jordanian labor market from early 2023 to September 23, 2025. Social security issues topped the list with 34 cases, followed by salary disputes with 30 cases, 24 cases of denial of holidays or annual leave, and 21 cases each of unfair dismissal and unpaid overtime, plus 14 cases of excessive working hours beyond legal limits.

Amina and her husband hold a refugee certificate from UNHCR. This document represents legal protection as refugees but can be revoked if they obtain an official work permit, shifting them to a "labor migration" status. Amina explains:“We want to work, but if we get a work permit, the UNHCR withdraws the refugee status. If we work without a permit, we are exploited and cannot complain.” Additionally, the cost of obtaining residency under Jordanian law on residence and foreigners exceeds the family's financial capacity.

According to UNHCR's website, only registered Syrian refugees are allowed to obtain work permits while retaining their refugee status; refugees of other nationalities do not enjoy the same right, placing them under additional restrictions that limit access to the formal labor market.

Tamkeen data confirms that denying Sudanese in Jordan-whether refugees or asylum seekers-the right to formal employment directly pushes them into the informal market as the only means to secure a livelihood.“The lack of legal job opportunities, the complexity and cost of work permits, make access to the formal labor market extremely difficult. These policies leave them with two harsh choices: either remain without sufficient income, enduring poverty and deprivation, or join the informal economy, exposed to exploitation and weak legal protection.”

Shereen Mazen, Tamkeen's Media and Communications Officer, notes that work permit procedures are limited to ten professions, requiring a valid legal residence-almost impossible for them due to strict conditions like depositing 25,000 JOD, marrying a Jordanian citizen, or being sponsored by an employer proving no Jordanian can perform the task.

As a result, most of these refugees suffer noticeable economic hardship, often relying on unsustainable coping strategies such as reducing meal frequency or portions, borrowing small amounts from friends, or sharing housing units with other families to bridge income gaps. Those with medical needs or chronic illnesses face compounded challenges due to high treatment costs and lack of a regular income source, Mazen adds.

Facing the Threat of Deportation

The situation of Hamed (39) is similar to that of Amina and her husband. He fled his country in 2018 seeking safety, carrying hope for a fresh start upon arrival in Jordan, only to find himself trapped between asylum restrictions and the difficulties of daily life.

It took him two full years to obtain official refugee status, during which he had to work informally at a car rental office, washing vehicles all day to provide minimum sustenance for his family in Sudan, as he is their sole provider. His employment status remained uncertain, constantly threatened by deportation to the country he fled.

Hamed spent two years and seven months in prison, and his release required a Jordanian sponsor-a challenging task for someone with limited networks in the host country. Eventually, through an acquaintance, he found a sponsor but at a cost of 200 JOD, and he remains obligated to pay ongoing fees to maintain the sponsorship. His fate is tied to this sponsor's discretion; if revoked, he risks returning to prison.

Jordan lacks a dedicated law regulating refugee status; they are instead subject to the Residence and Foreigners Law and the Labor Law, explains Dr. Ayman Halsa, professor of international law. These laws are insufficient as they do not distinguish between "foreigners" and "refugees" nor address special protections, leaving refugees vulnerable to deportation like any other foreigner violating residence regulations.

Internationally, Jordan has not ratified the 1951 Refugee Convention nor its 1967 Protocol, meaning it is not legally bound by their standards, including the right to work, and has weak safeguards against forced return. Halsa notes that the 1998 Memorandum of Understanding between the Jordanian government and UNHCR is a positive step but falls short of binding national legislation, relying on authority cooperation and primarily defining UNHCR's obligations in refugee registration and permanent solutions.

Systematic Exploitation

Abdulhadi (40) spent about three years working in a commercial shop in Aqaba, southern Jordan, yet his employer deducted part of his monthly wages and failed to pay him fully, accumulating unpaid wages up to 2,750 JOD. Despite repeated demands, the employer evaded payment and continued delaying with false promises.

Abdulhadi, a father of three, emphasizes that working in the informal market was not a choice but a forced necessity due to legal restrictions and harsh living conditions.“We work informally because we have no other way to survive. We are compelled by strict laws. This is how we try to save our lives, otherwise my children and I would face the risk of starving, given the lack of UNHCR support.”

Regarding recurring exploitation, he adds:“Once you apply for any job, the employer realizes you hold a refugee certificate that doesn't allow you to work officially, making you directly vulnerable to exploitation. Often, salaries are delayed or unpaid, with no means to defend your rights.”

Tamkeen notes that Sudanese participation in the informal economy not only deprives them of legal protection but traps them in systematic exploitation, difficult to escape without policy reforms. The informal market lacks effective legal oversight, written contracts, labor inspections, and official wage records, creating a power imbalance favoring employers.

In some cases, violations approach human trafficking, including withholding official documents, restricting movement, threats of arrest or deportation, or forcing long work hours without pay, especially when coupled with coercion, deception, or continuous control over the victim.

Halsa and Mazen agree that the absence of formal employment weakens these workers' ability to claim rights or seek legal recourse, fearing loss of income or legal repercussions due to their unstable status. Halsa explains:“In theory, Jordanian labor law and anti-trafficking law protect all workers regardless of nationality, and they can approach courts or the Ministry of Labor if exploited. In practice, the lack of work permits prevents rights claims. Most undocumented Sudanese fear filing complaints due to deportation risk, and practical protection is extremely limited.”

Tamkeen emphasizes that, although the legal framework is comprehensive on paper, there is a real gap in application for refugees and asylum seekers from“non-Syrian” nationalities like Sudanese. Accessing protection requires a valid work permit, rarely available to them. Even when attempting to file complaints, high financial and procedural costs pose further barriers, limiting their ability to benefit from legal protection. Integrating Sudanese into Jordan's formal labor market is not just a humanitarian response, but a strategic choice with dual benefits: guaranteeing workers' basic rights, enhancing economic and social security, reducing labor violations and tax evasion, promoting equal opportunity and social justice, lowering poverty, reducing dependency on humanitarian aid, and creating a more transparent, reliable work environment-boosting overall economic productivity.

All names in this report are pseudonyms to protect privacy.

This report was produced under the“Enhancing Migrant Workers' Rights and Combating Human Trafficking” project, implemented by the Information and Research Center–King Hussein Foundation, in collaboration with Heinrich Böll Foundation – Palestine and Jordan Office. The views expressed do not necessarily reflect those of the Heinrich Böll Foundation.

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the

information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept

any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images,

videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information

contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright

issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Comments

No comment