Indonesia-Malaysia Chart A Course For Calming Disputed Seas

After years of stop-start talks and periodic flare-ups at sea, both sides now say they plan to pursue joint economic development of the block's rich oil and gas reserves, with lawyers reportedly working on a mutually acceptable sea boundary.

On paper, it marks a pragmatic pause in a longstanding dispute dating back to Malaysia's 1979 map that claimed parts of the Sulawesi Sea. In practice, however, it could become either a disciplined bridge to legal certainty or a cul-de-sac that breeds more drift, suspicion and copycat ambiguity across Southeast Asia's many contested sea areas.

This piece argues for the first path. Ambalat can be more than a risk-management device; it can be a model if Jakarta and Kuala Lumpur design it with transparent economics, real environmental guardrails and a clear legal horizon consistent with the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

To get there, the two neighbors should lean on what works in the region, avoid temptations that have sunk other arrangements and speak plainly to their own publics about tradeoffs.

Why does Ambalat matter now? Indonesia and Malaysia have lived with an unresolved line in these waters for decades. Each side has issued oil and gas concessions in overlapping zones. Patrol vessels have shadowed one another, while the dossier has never strayed far from nationalist talking points.

The dispute was complicated by the International Court of Justice (ICJ) rulings on nearby features-Ligitan and Sipadan went to Malaysia in 2002; Pedra Branca went to Singapore in 2008, with Middle Rocks to Malaysia-decisions that sharpened domestic sensitivities without settling the Ambalat line itself. In short: the court victories and losses changed emotions more than maps.

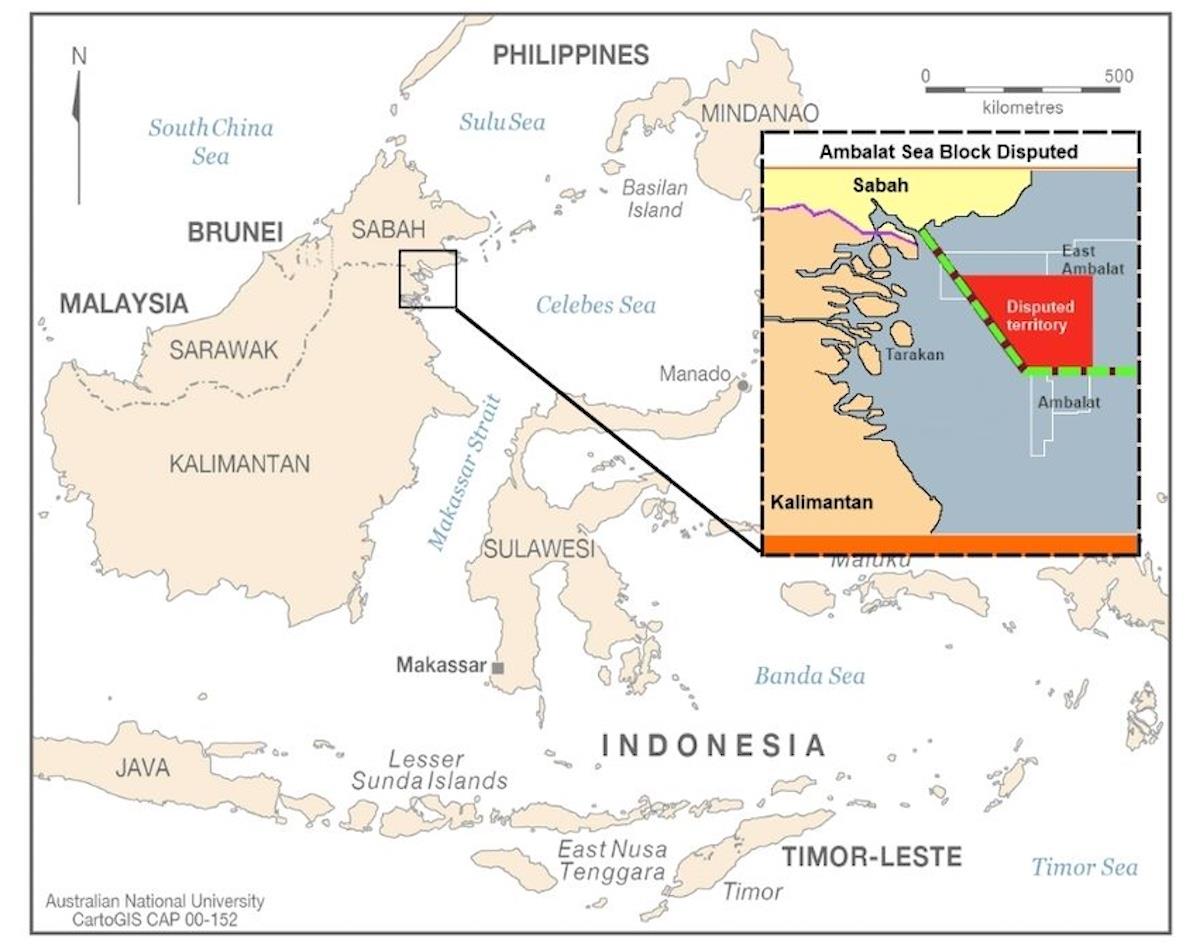

Ambalat area of dispute. Map via ANU Open Research Repository and WikiMedia Commons

UNCLOS anticipates precisely this kind of stalemate. Articles 74(3) and 83(3) tell states with overlapping claims to“make every effort to enter into provisional arrangements of a practical nature” and, crucially, not to jeopardize a final delimitation. Provisional arrangements are bridges, not destinations.

Latest stories

Russia aiding and abetting North Korea's nuke sub dream The center cannot hold: Structural fatigue across Ukraine, Germany, and Japan

Witch hunts, blacklists and the new American McCarthyism

A joint development zone that lacks sunset clauses, hard review dates or an agreed mechanism to convert practice into a boundary will skate against the spirit of the convention. Lawyers can argue about form; what matters in policy is function: will the arrangement lower incentives for delay and raise incentives for settlement? If not, it's an elegant way to park a problem indefinitely.

The latest turn-high-level endorsement of“joint development while legal talks continue”-arrived after meetings between Indonesian President Prabowo Subianto and Malaysian Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim. Both leaders have framed the approach as a peace-first, economics-forward posture that fits their wider foreign policy messaging.

That rhetoric matters: it signals a decision to transform a sovereignty contest into a governance test. But the text under the headlines will determine whether Ambalat stabilizes or frays.

Domestic dividends if it worksSoutheast Asia is in a long test of whether norms can discipline power. The South China Sea remains contested despite a 2016 arbitral award favoring the Philippines against China. ASEAN's code of conduct talks on the sea have inched forward at a snail's pace without locking in any enforcement teeth.

In that environment, how Indonesia and Malaysia manage a difficult but tractable bilateral issue will be read closely. A crisp, provisional Ambalat deal anchored in UNCLOS would strengthen ASEAN's quiet case for rules. A murky, open-ended patch would weaken it. Neighbors are watching. So are extra-regional players, spelled China, who prefer ambiguous spaces.

For Indonesia, a clean Ambalat regime would showcase the country's preferred identity: a confident maritime power that marries principle with practicality. It would also dovetail with broader defense and coast guard reforms aimed at de-conflicting gray-zone encounters.

For Malaysia, especially Sabah, visible co-benefits-jobs, local funds and cross-border programs-could transform Ambalat from an abstract grievance into a working asset. Both governments would get something rare: a cross-border success story that doesn't rely on great-power mediation.

Several questions, however, may arise along the way. Isn't joint development a giveaway? No-if the deal is fenced and timed. Each side can explicitly preserve its legal positions. The point is to harvest value while buying space for a disciplined legal process.

What if talks collapse? Build off-ramps. If legal negotiations fail to meet milestones, certain concessions may be paused and the parties move to a pre-agreed dispute-settlement step. Uncertainty persists, but risk becomes managed, not chaotic.

Won't this embolden non-compliant actors elsewhere? Quite the opposite-if Ambalat is tightly welded to UNCLOS text and process. It may model how states can avoid escalation without normalizing legal vagueness. The worst message to send is that“ambiguity pays.” The best is that“provisional arrangements speed settlement.”

Three recommendations-simple, hard and necessaryFirst, legally anchor the joint zone. Write into the instrument that the arrangement is provisional under UNCLOS Articles 74(3) and 83(3), without prejudice to final delimitation. Add a five-year sunset clause that automatically forces a legal step (conciliation, arbitration, or court) unless both sides certify concrete progress.

Second, design for daylight. Create a two-country joint authority with a micro secretariat and macro transparency. Open contracting, beneficial-ownership disclosure, independent audits and a public data portal. Earmark a fixed percentage of gross revenues to border-district funds on both sides, with line-item project lists.

Third, green the hydrocarbons. Mandate baseline ecological surveys, routine monitoring, public incident logs and pre-agreed stop-light thresholds; set aside a restoration fund financed by a small levy per barrel equivalent. Tie permitting to compliance.

The alternative is drift – and drift is expensive. Critics will say that boundary talks can fail and that joint development can lull capitals into complacency. They're right, which is why Ambalat must be built as a ramp, not a hammock.

Sign up for one of our free newsletters

-

The Daily Report

Start your day right with Asia Times' top stories

AT Weekly Report

A weekly roundup of Asia Times' most-read stories

Others will warn that putting numbers on revenue splits or dates on reviews gives ammunition to nationalists. True again-and exactly why leaders should speak directly to their citizens about the logic: certainty raises value; transparency lowers suspicion; and provisional arrangements, done right, shrink the space for accidents and miscalculation.

Prabowo and Anwar have agreed that joint development is the key to solving their Ambalat problem. Image: X Screengrab

There's also a geopolitical dividend. A working Ambalat sends a message that Southeast Asian states can solve hard problems with law, engineering and diplomacy-without needing to borrow frames from bigger powers.

It would show that“ASEAN centrality” can be something more than agenda-setting; it can be norm-setting by example. That won't end great-power pressure in contested seas. But it will tighten the region's fabric against it.

Finally, don't let a good idea go vague. Joint development is not original. What would be original is doing it in a way that actually accelerates legal closure, sustains domestic legitimacy and protects a living sea. Ambalat offers Indonesia and Malaysia that chance. The neighbors should seize it-eyes open, documents tight and clocks running.

If they do, a once-combustible corner of the map could become a quiet proof of concept for the wider Asia-Pacific: you don't have to pick between principle and pragmatism; you can design them to reinforce each other.

AD Agung Sulistyo is a researcher on Southeast Asian diplomacy and transnational law, and research fellow at the RIAP Institute. He is based in Jakarta.

Sign up here to comment on Asia Times stories Or Sign in to an existing accoun

Thank you for registering!

An account was already registered with this email. Please check your inbox for an authentication link.

-

Click to share on X (Opens in new window)

X

Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

LinkedIn

Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

Facebook

Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

WhatsApp

Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

Reddit

Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

Email

Click to print (Opens in new window)

Print

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the

information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept

any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images,

videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information

contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright

issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Most popular stories

Market Research

- Stocktwits Launches Stocktoberfest With Graniteshares As Title Partner

- Phase 6 Reaches 50% Mark As Mutuum Finance (MUTM) Approaches Next Price Step

- Cryptolists Recognised As“Crypto Affiliate Of The Year” At SBC's Affiliate Leaders Awards 2025

- BTCC Exchange Announces Triple Global Workforce Expansion At TOKEN2049 Singapore To Power Web3 Evolution

- Moonbirds And Azuki IP Coming To Verse8 As AI-Native Game Platform Integrates With Story

- Fanable Gets $11.5M To Power The Future Of Pokémon & Collectibles $COLLECT Token Farming Goes Live Now

Comments

No comment