East Of Empire: Partitioning Of India And Palestine Unleashed The Violent Conflict That Continues Today

How did Muhammad Ali Jinnah go from being a secular young man appalled by Indian interference in the Ottoman Caliphate crisis to the moving spirit behind the demand for Pakistan – a new Islamic nation which, he claimed, would be capable of defending Muslims abroad?

These are the kinds of questions that kept me awake at night for years. The result of that insomnia is my new book , East of Empire: Egypt, India, and the World Between the Wars.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here .

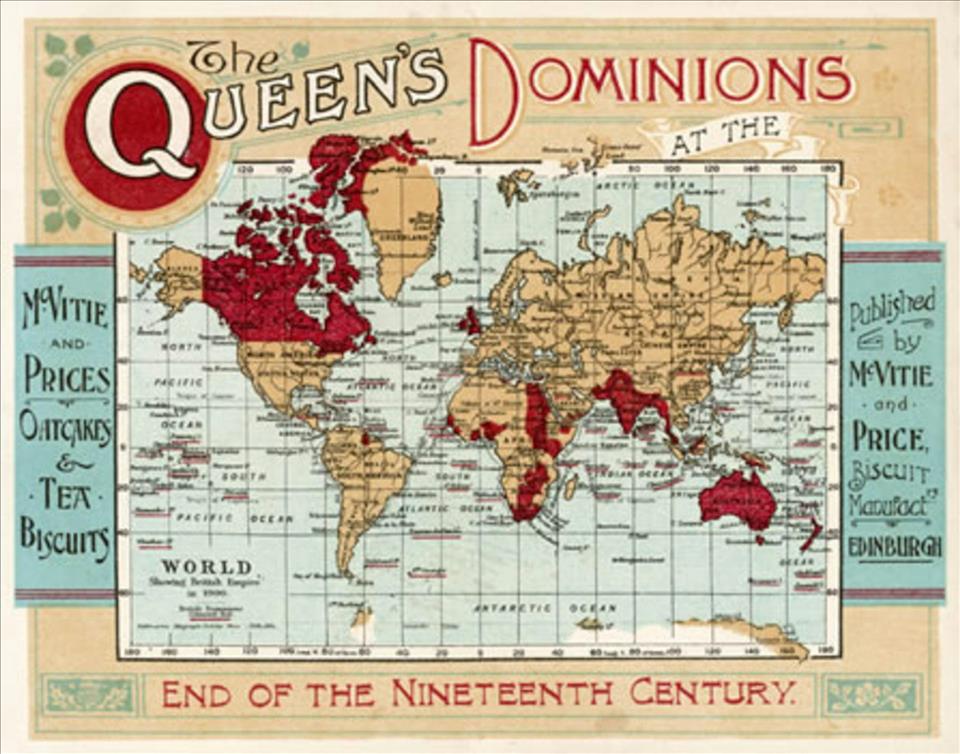

My focus is the quarter-century which immediately preceded the end of empire in India-Pakistan and Palestine-Israel . Both countries were partitioned along ethnic lines – the former by the British and the latter by the UN – resulting in catastrophic bloodshed and the forced displacement of millions .

These partitions took place barely six months apart, between 1947 and 1948. They remain at the heart of horrific state violence on both continents, not to mention intergenerational trauma and rancorous historical debate.

For much of the period my book deals with, from 1919 until the mid-1930s, the division of territory between religious or ethnic blocs would have been difficult for most people living in the Middle East and South Asia to fathom. There were no obvious frontiers that could be drawn between local communities. Particularly in cities and towns, neighbours of different ethnicities and faiths lived cheek by jowl.

Mountbatten discusses plans for partition in June 1947 with Nehru and Jinnah, who would become the first leaders of India and Pakistan respectively after British rule ended. Keystone Press / Alamy

In fact, it was precisely during this time, between the first and second world wars, that Egyptians and Indians came to think of their movements for self-determination as shared across communal divides.

Artists, politicians, activists and intellectuals described a thick and flexible web of interconnections – some spiritual or linguistic, others cultural and geopolitical – which together made up something called the sharq, orient, or“east”. This was said to transcend all kinds of barriers, depending on who you asked – creed, language, ethnicity, nation, gender and class, for starters.

Many historians writing about this period have picked up this“easternism” for closer inspection – only to swiftly place it back down again. They argue it is too vague, amorphous and internally contradictory to be of much use as an analytical category. They are not wrong. Between the 1920s and '40s, there were many (perhaps even countless) visions of the east in circulation.

There was the east of orientalists – foreign, exotic and“other”. There was the anti-colonial east, a geography of allies in the battle against foreign domination. Then there was the spiritual east, often contrasted with the materialist west. There was the Islamic east, a region populated largely (though never exclusively) by Muslims. There was also the cosmopolitan east, a rich tapestry of cultures bound together by commerce and exchange of ideas. Finally, there was the strategic east, a geopolitical bloc or bulwark that might counter other constellations of power.

It is important to underscore that none of these concepts were mutually exclusive. Instead, proponents of easternism tended to connect several“kinds” of eastern ideas together into a personally appealing hybrid.

Egyptians gather in Opera Square, Cairo, in December 1947 to protest against the UN partition of Palestine. AP / Alamy

Thus in his memoir, Sultan Mahomed Shah, Aga Khan III , revisited his long-cherished dream of an eastern bloc of Muslim nations, serving as both a moral compass to the world and a healthy check on the power of Europe and the United States.

For the Egyptian feminist Huda Shaarawi , the east was unapologetically anticolonial. In the pages of her magazine, l'Egyptienne, it was frequently ancient and exotic – but also, crucially, a stage upon which women from many cultural, ethnic and religious backgrounds would together forge the future in their own image.

Given the dizzying array of potential easts, it was never what academics would call a coherent ideology. But this did not prevent it from being a highly prominent feature of both political debate and action in Egypt, India and the broader Arab-Asian region throughout the interwar period.

Beginning in the 1920s and deep into the '30s, various eastern visions flowed in and out of alignment with one another as headlines changed, alliances evolved, and priorities shifted. With the onset of war in Europe in 1939, however, the stakes of these ideological differences began to spike.

Stanford University Press

Subjected to the unrelenting pressure of war, the many strands of easternism began to splinter, putting paid to the more fluid and open-ended possibilities that had animated preceding decades.

In their stead emerged postwar ideologies with sharper edges, hardened national frontiers, and – following years of globally cataclysmic violence – little faith in the pacifist and humanist ideals of a bygone era. This almost chemical transformation is the backdrop against which votes affirmed the partitions of India and Palestine in 1947.

Here, then, is the story told in East of Empire: how visions of a transnational, fluid and nonconformist east shaped the interwar politics of India and Egypt, and why these visions gave way to a more rigid, militant nationalism by the end of the second world war.

The book revisits a near-forgotten chapter in the rise of anticolonialism and the end of the British empire across the Middle East and South Asia. And it explains the conditions under which these bold and optimistic visions buckled – unleashing torrents of violence we have yet to staunch, almost 80 years later.

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the

information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept

any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images,

videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information

contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright

issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Comments

No comment