Argentina: Javier Milei's Government Poses An Urgent Threat To Human Rights

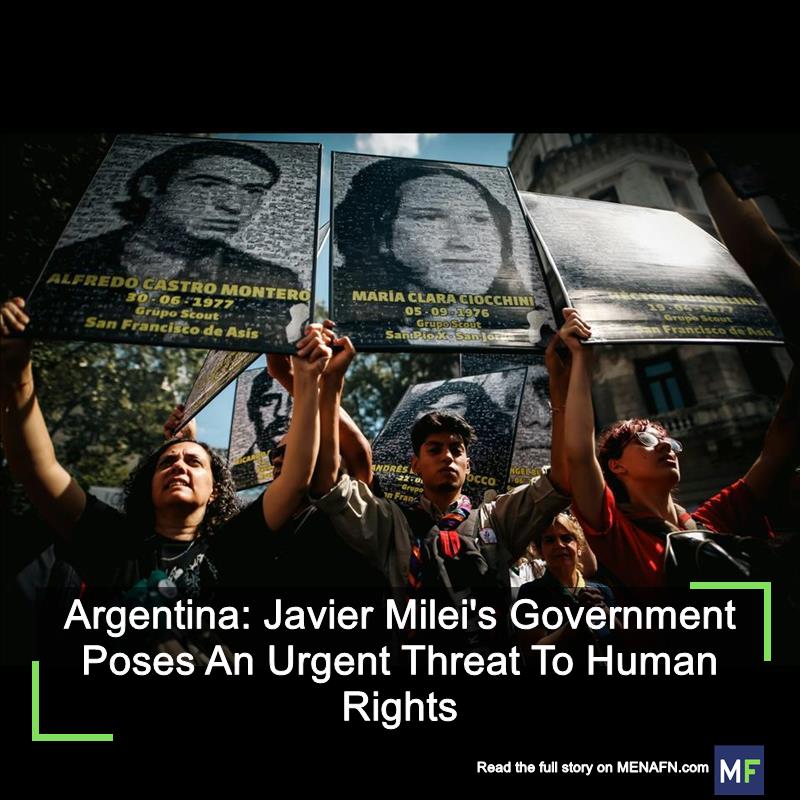

People flock to Buenos Aires – and other cities across Argentina – on this date each year for an annual march to commemorate the victims of the country's last military dictatorship. Between 1976 and 1983, an estimated 30,000 people were killed, imprisoned, tortured or forcibly disappeared in a state-led campaign that still haunts the country.

But this year the march felt a little different. Activists showed their palpable outrage at President Javier Milei's administration for seeking to downplay the brutal legacy of the dictatorship.

And on March 21, Milei's defence minister, Luis Petri, reportedly met with the wives of military officers convicted of crimes against humanity. The meeting occurred amid rumours of pardons for human rights abuses that had been committed under the dictatorship.

Many human rights have been rolled back too. Activists have faced threats, funding for the country's commemorative sites has been withdrawn and their staff laid off, and workers in the Secretariat of Human Rights have been sacked . Human rights, which have been hard won over decades in Argentina, are in danger.

People gather in cities across Argentina on March 24, the anniversary of a coup that installed a brutal military dictatorship in Argentina. AstridSinai/Shutterstock Political violence

Milei is a self-professed anarcho-capitalist. His policies are at best, nebulous, and at worst, dangerously chaotic. Since he was elected in November 2023, Milei has made clear plans for sweeping liberal economic reforms, cuts to funding for public services, and has opposed equal marriage and legal abortion.

Read more: Argentina's anti-government protests offer a lesson for the international struggle against the rise of the far right

Milei's human rights policy is worrying . A number of active and retired military personnel have been appointed to various government positions, including chief of staff and to the Ministry of Defence. However, there would be worse to come in the run up to this year's March 24 commemorations – an outright assault on human rights.

In early March, Sabrina Bölke, a member of HIJOS (Sons and Daughters for Identity and Justice against Oblivion and Silence), was attacked and sexually assaulted in her home. HIJOS is an Argentinian organisation founded in 1995 to represent the children of people who had been murdered, disappeared or imprisoned by the country's military dictatorship

Before leaving, her attackers wrote“VVLC [viva la libertad, carajo] ñoqui” on one of the walls. This is Milei's catchphrase and loosely translates as“Long live freedom, dammit”. Ñoqui (gnocchi) is a derogatory term for state workers, equivalent to“jobsworth” in English.

This is a lesson in what happens when radical“outsiders” like Milei (or Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil and Donald Trump in the US) come in from the shadows. They not only tolerate political violence, but actively encourage it. Lacking political experience, their leadership is founded on creating an“us v them” mentality which emboldens their supporters.

Revising historyThe day of commemoration brought one more disturbing turn of events. The government released a video straight out of the denialist playbook, presenting a false, alternative portrayal of the military dictatorship's crimes.

The video advocates for a“complete memory” that shifts the focus to those killed by armed left-wing organisations in the 1960s and 1970s and calls for the end of the pursuit of justice for military perpetrators. It stars Juan Bautista Yofre, the ex-chief of the Secretariat of Intelligence, and María Fernanda, the daughter of Captain Humberto Viola, who was killed in 1974 by the revolutionary left.

The video resurrects the“two demons” trope. This is a theory that equates systematic state terrorism with the violence committed by the revolutionary left. It justifies the disappearances as the result of a conflict between two warring factions.

It's a viewpoint that had, in recent years, lost much credibility. In 2006, the prologue to the National Commission on the Disappearance of Persons' truth commission report , which was originally published in 1983 to detail the extent of forced disappearance across Argentina, was rewritten specifically to remove allusions to this myth.

Such rejection of historical facts is not surprising. During his presidential campaign debates, Milei disputed the number that had disappeared at the hands of the dictatorship.

His vice president, Victoria Villarruel, the niece of a member of the armed forces under judicial investigation, has gone even further. She has called for an end to human rights trials and has pushed for the closure of the memory museum on the grounds of what was once the notorious former Navy Mechanics School that became a clandestine detention centre during the dictatorship.

The president of Argentina, Javier Milei (left), and his vice president, Victoria Villarruel (right). Luciano Gonzalez / EPA What happens next?

Milei and Villarruel may struggle to block human rights trials completely, certainly not without a stand-off with the Argentine courts. The opposition of congress to Milei's“omnibus law” (the collective name for his package of liberal reforms) in February 2024 is a reminder that he will undoubtedly face legislative roadblocks.

The Argentine Court of Appeal, which is responsible for ruling on human rights cases, has also been clear that it will prevent perpetrators of human rights abuses benefitting from house arrest. However, we will probably see a gradual undermining of judicial processes via the release of defendants and the replacement of judges, accompanied by an emboldening of those who deny state terrorism.

It is still early days in Milei's tenure. But human rights activists and international observers should be concerned about the future of human rights in Argentina.

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the

information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept

any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images,

videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information

contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright

issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Comments

No comment