Asia 2026: 10 Questions For China's Year Ahead

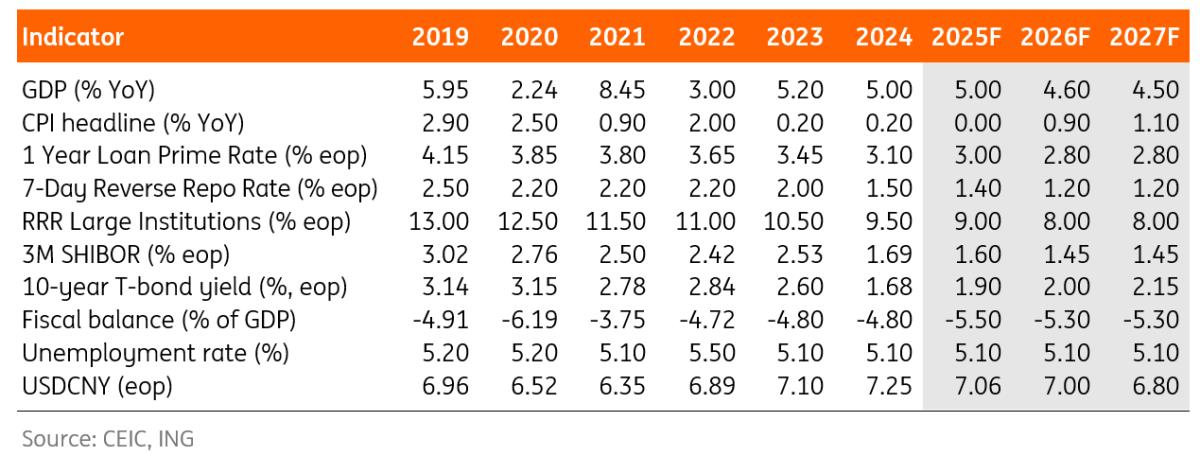

We are looking for a slight slowdown in Chinese growth to around 4.6% year-on-year in 2026, which, in our interpretation, qualifies as another year of stable growth.

China looks likely to achieve another year of“around 5%” GDP growth in 2025, as a strong start to the year – driven by resilient external demand and a boost to consumption from the trade-in policy – should be a sufficient buffer against slowing growth in the second half of the year.

Premier Li Qiang revealed that the Chinese government aims to reach a GDP of RMB170tr by 2030, which will require growth of around 4-5% in the coming years. To get off to a strong start, we believe that China could once again target growth of“around 5%” in 2026 for a fourth consecutive year. The odds of the goal being softened to“above 4.5%” are increasing, though China has not held the same growth target for more than three consecutive years since 2011.

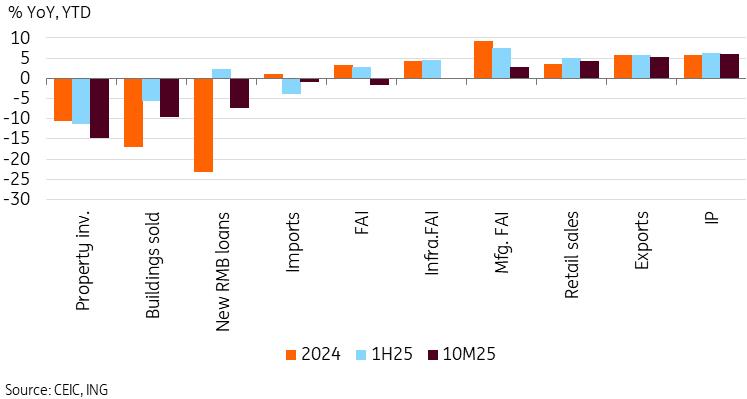

From where the economy currently stands, this doesn't look to be a simple task. Fixed-asset investment has slumped to negative levels for the first time since the lockdown impacted the year of 2020. Consumption has shown signs of slowing as the impact of the trade-in policy gradually shifts from a tailwind to a headwind. All of this is translating into a contraction in new renminbi loans.

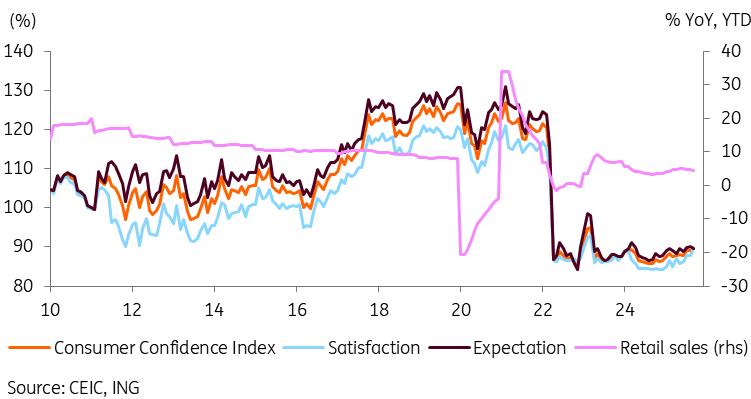

The overarching problem is that domestic confidence indicators remain weak. This is likely tied to the continued downturn in the property market, as well as years of cost-cutting that led to wage cuts and layoffs. Stimulus might prove less potent without addressing these core issues.

External demand has been a notable driver of growth in the past two years. It's uncertain whether momentum can be sustained for a third year straight. If this engine begins to slow, the outlook will become considerably more difficult. This would be one of the biggest downside risks to the scenario.

China's policy execution and its timing present major uncertainty to the outlook as well. While stronger early growth may have reduced the urgency for new stimulus in the fourth quarter, a broad-based slowdown of growth would signal that more support may be needed in 2026. What this ends up looking like, and the timing, will play a big role in shaping the growth trajectory.

Upside risks in our view could come from developments in key tech races, including AI+ products, robotics, and biotech. China's strategy for the next five years will be concentrated on industrial modernisation and technological development to move up the value-added ladder. A tech breakthrough that generates a new wave of demand could be a notable growth driver for years to come.

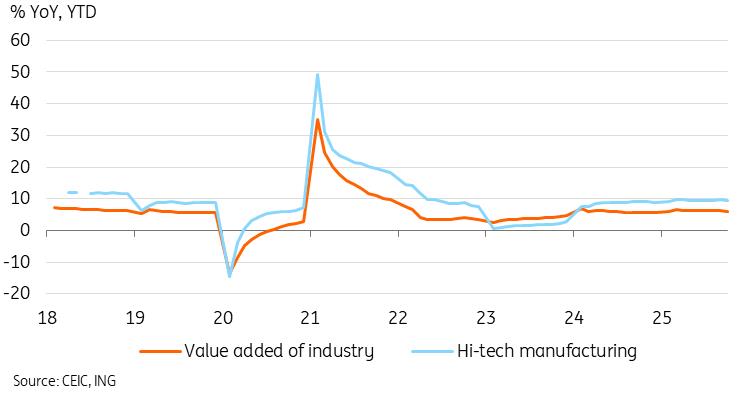

China's growth was supported by resilient external demand despite the trade war

Can China's trade resilience last?

Our base case is a slight moderation in external demand in 2026. But one of the main risks is a worse-than-expected deterioration in the external demand outlook. China's exports have been a relative outperformer for the last two years. Industrial activity has also seen solid growth to service this external demand.

The big surprise of 2025 was the resilience of Chinese exports despite the outbreak of Trade War 2.0 with the US. Recall this time last year. Many analysts had been forecasting a sharp slowdown in China's GDP, with the more bearish forecasters factoring in a drag of 2-3ppt to growth. Instead, through the first 10 months of the year, China's exports grew 5.3% year-on-year, and its trade surplus rose 22.1% to $964.8bn.

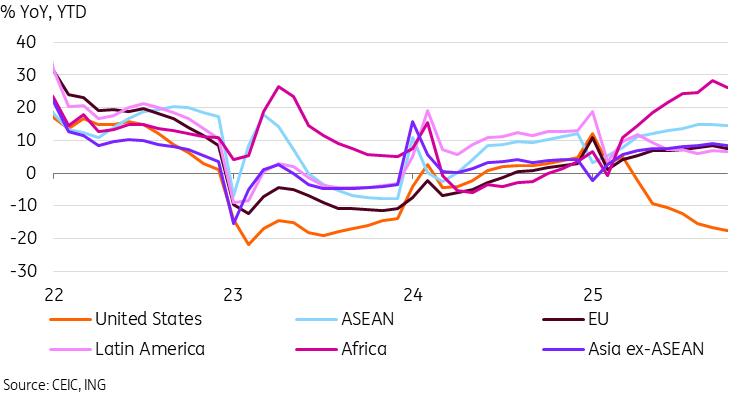

One initial reaction might be to assume that tariffs have had a limited impact. This would be a mistake. Exports to the US are down 17.7% YoY, year-to-date, through October 2025, and the contraction looks likely to deepen as the year closes out. Export categories that rely heavily on the US, such as furniture, footwear, and toys, all saw exports contract.

China's export resilience can be credited to two main factors. First, exports have been diversified successfully to other regions, with ASEAN (14.5%), the EU (7.7%), India (13.3%), and Africa (26.2%) all showing solid growth. Second, China's fastest-growing exports, such as electric vehicles, lithium batteries, semiconductors, and ships, have very limited US exposure.

Will this resilience last? It's not certain that external demand will hold up. Our ING forecasts generally show slightly slower growth in key economies next year. Absent any new catalysts, this backdrop could translate to slower demand growth for Chinese exports. Recent flare-ups with Japan and the Netherlands are a reminder that the external environment can be quite unpredictable.

On China's trade with the US, markets breathed a sigh of relief after a one-year truce was agreed when Chinese President Xi Jinping and US President Donald Trump met in South Korea. However, it should be noted that the tariffs on China, currently at around 47%, remain well above the 20.7% level before Trump's inauguration. Combined with the front-loading of trade seen in the first quarter, it's likely that exports to the US will remain under pressure at least until the second quarter of 2026.

Though the agreement is for a year, it should be noted that there's no guarantee this uneasy truce will last that long. A lot needs to go right for the agreement to hold for the full year. While there's the potential for a rebound of exports to the US next year, it's far from guaranteed. One miscalculation and we could easily see a re-escalation of tariffs and tensions.

Trade remains difficult to forecast even in calmer waters, but at this juncture, it seems prudent to expect a softer external demand backdrop for next year.

Exports to other regions have helped offset tariff impact in 2025

Can domestic demand pick up the slack?

China has often invoked the idea of a“dual circulation strategy,” in which growth is driven by two“loops” – an external one tied to global trade and investment, and an internal one driven by domestic demand and self-sufficiency in key technologies.

We've seen the external loop do much of the heavy lifting in the last few years. However, the internal loop has shown mixed results as of late, with consumption recovering in 2025 but investment declining.

If our view of a less supportive external demand environment materialises, China's growth outlook will require the internal loop, namely domestic demand, to pick up the slack. The ability to do so will likely hinge on what policy initiatives China uses to support domestic demand.

Consumption has benefited over the past few years from China's trade-in policy, a de facto subsidy for specific consumer products. Beneficiary categories have included autos, household appliances, consumer electronics, and furniture, and these categories saw major outperformance in their respective policy windows.

However, the trade-in policy essentially front-loads consumption and has limited lasting power. The logic is simple. While households may choose to buy a new car or washing machine when it comes with a nice discount, they likely won't immediately buy another one next year, even if the discount remains. As we have seen with automobiles, after a surge in sales during the early stages of the trade-in policy, sales flatlined in subsequent years. This pattern appears to be repeating with household appliance sales in this year's fourth quarter, and the same could occur in consumer electronics and furniture in 2026.

This means either expanding the trade-in policy to other categories or adopting a new policy to support consumption next year. Given the increased focus on services, expanding consumption vouchers for the services sector could be considered. Other moves, such as adjusting tax brackets, are possible but may be difficult to implement amid fiscal pressures.

On the investment side, while a recovery is possible as sidelined corporates resume new investments, we don't yet see signs of a major turnaround coming in 2026. China's 'anti-involution' policy to combat extreme price competition, along with comments from the 15th Five-Year Plan, suggest that cutting down on redundant investment will be a priority. The same goes for recalibrating incentives to align with a national, rather than a regional-focused, development strategy. These are positive steps that could well reduce overcapacity and improve the efficiency of future investment. But they will likely result in short-term headwinds amid stricter investment approval processes and greater caution in how funds are spent.

The core issue holding back domestic demand, in our view, is increasingly entrenched pessimism across households and the private sector. Chinese households have one of the highest savings rates globally. Convincing them that it is okay to lower these savings will be a tall task.

Most confidence indicators have been grinding a little higher over the past year, but remain much closer to the historical low than to the historical mean. Our view is that for confidence to recover, we need to see a stable, if not positive, wealth effect. This hinges in large part on the recovery of the housing market. We also need to see an exit from the cost-cutting environment that has set in in the workplace. Both of these are much easier said than done. In the meantime, policies to boost short-term consumption may be needed to keep growth afloat.

Weak consumer confidence remains a challenge

Can China finally put the brakes on the property decline?

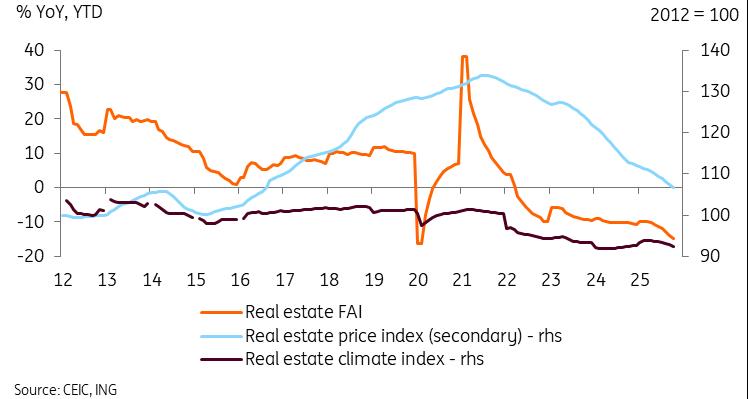

We were much more optimistic about the property market this time last year, when policymakers were regularly lifting purchase restrictions and rolling out policies to support it. This optimism proved to be misplaced. Policy support slowed in 2025, and we've seen a concerning re-acceleration of falling property prices. In October, China's 70-city property prices saw secondary-market prices fall by more than 20% from the peak.

Recent signals haven't been encouraging either. Former Minister of Finance Lou Jiwei stated that the property slump will continue and could hinder growth for another five years. It doesn't sound like a panacea is around the corner, with policy signalling suggesting that avoiding major systemic risks is enough. With property developer defaults slowing for another year, the bright side would be that systemic risks indeed look limited.

As such, a V or U-shaped recovery is looking quite improbable. An L-shaped recovery establishing a trough might be a more realistic bull case for 2026. That said, the importance of property to domestic confidence cannot be overstated. There will still be pressure to step in if the downturn worsens. For now, market reports indicate that policymakers are considering mortgage subsidies for new homebuyers, raising tax rebates for property purchases, and lowering home transaction fees. We expect that, in addition to these proposals, further support is needed to remove the remaining purchase restrictions and ramp up government purchases of unsold homes.

The bear case is that officials simply let the downturn play out. While a new market equilibrium would eventually be reached through market forces alone, it could take an extended period at the cost of significant wealth destruction and more entrenched deflationary expectations. This would have significant implications for China's longer-term economic transition, notably by hindering efforts to strengthen domestic demand.

Price trajectory aside, housing inventory remains highly elevated. Until inventories normalise, it will be difficult to expect a turnaround in real estate investment. As such, even though the base effect is weak, another year of contracting property investment growth looks likely.

At the least, a true property turnaround doesn't look likely to be a 2026 story, barring a major change of heart from policymakers. Property will likely remain one of the biggest drags on the economy next year.

Real estate sentiment and investment remain downbeat as prices keep falling

Will China's tech 'gold rush' lead to riches or ruin?

Policymakers have heavily leaned into tech and innovation as part of the national development strategy. Tech was the top priority for China in the 14th Five-Year Plan (FYP), and remains a prominent part of China's growth strategy in the 15th FYP.

Increased sanctions targeting Chinese companies have strengthened the tech self-reliance drive, spurring the creation of domestic champions. Once seen as a one-horse race in which the US was preordained to win the AI race, China's breakthroughs this year prompted some to reevaluate.

China's tech push has had numerous real-world implications:

-

China's fastest-growing trade categories are often tech-related. In the first 10 months of the year, hi-tech imports rose by 14.1% YoY to $79.5bn, while hi-tech exports rose 6.8% to $684bn. Prior investment in EVs has made China not only the world's largest producer and exporter of EVs, but also its largest consumer.

Many tech-related sectors have been attracting the most investment in recent years, and growth has remained solid despite the overall weak investment environment. Aside from the EV, battery, and semiconductor industries, which we often discuss, China's grid investments in power data centres have also risen 10% YoY YTD in a year of otherwise soft investment.

The tech race has increased the need for China to improve its domestic semiconductor industry. This has translated into a 35.3% YoY YTD uptick in semiconductor manufacturing equipment imports through 3Q25, while direct semiconductor imports have risen only 8.8% YoY YTD. The recent buildup of China's domestic industry has also made semiconductor exports one of its fastest-growing categories, up 23.4% YoY through 10 months of 2025.

China's tech sector has outperformed equities amid the rally of the past year. At the time of writing, the Hang Seng Composite Index's IT subindex is up 51.9% on a 12-month basis, outperforming the HSCI's 37.2% return over the same period.

There have been numerous positive developments in China's hi-tech sector. In addition to the rising focus on semiconductor self-sufficiency, which has driven strong production and trade growth, we also saw some progress on the innovation front.

On AI, the“Deepseek moment” gathered the most attention abroad and illustrated the fruits of China's AI push. The China Academy of Information and Communications Technology (CAICT) estimates that the AI industry surpassed RMB 900bn in scale in 2024. The“Eastern Data, Western Computing” initiative, launched during the 14th Five-Year Plan, drove over RMB 1 trillion in investment and now supplies about 80% of the national intelligent computing capacity. We still see private-sector enthusiasm, too, including Alibaba's plan to invest RMB 380 billion in cloud and AI infrastructure over three years.

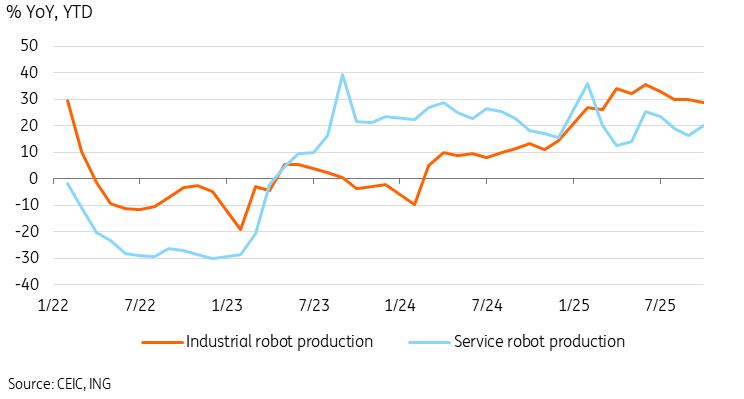

Robotics has also been an area of strong growth. Industrial robot and service robot production were up 28.8% and 20.0% YoY YTD in October, respectively. China's so-called“dark factories" are examples of robotics helping to automate production to an extent where human activity is minimal, allowing the factories to operate in the dark. Recently, Xpeng's Iron robot went viral for its humanlike movements. We've seen a variety of new robot functionalities this year, including robots acting as baristas, popcorn servers, boxers, and even performing surgeries.

At the same time, this imbalance raises the question of what the impact would be on China's economy if it lost the AI race or if AI or tech exuberance faded?

At the time of writing, more market participants have been debating whether the AI exuberance has gone too far and whether we're now facing a second dotcom bubble.

During China's National Urban Work Conference, the central government highlighted concerns about local governments' excessive investment in AI, computing power, and new energy. Similar to previous strategic industries, though, this strategy can result in the emergence of national champions. This may raise the risk of over-competition and poor resource allocation, especially as banks are called upon to support the national strategy.

The National Development and Reform Commission also recently issued a warning on potential bubble risks for the humanoid robotics industry, citing the large number of similar robots under production across multiple companies, and vowing to speed up efforts to build mechanisms for market entry and exit to facilitate an environment for fair competition.

Winning the tech race would provide the most obvious catalyst for securing China's long-term growth trajectory. This is clearly spelt out in China's 15th FYP, which calls on tech and innovation to create more“new quality productive factors”. At the same time, it's wise not to put all the eggs in one basket, so to speak. Setbacks could result in numerous failed investments and further hits to sentiment.

Robotics production has surged amid new advancements

Will China be able to break out of deflation?

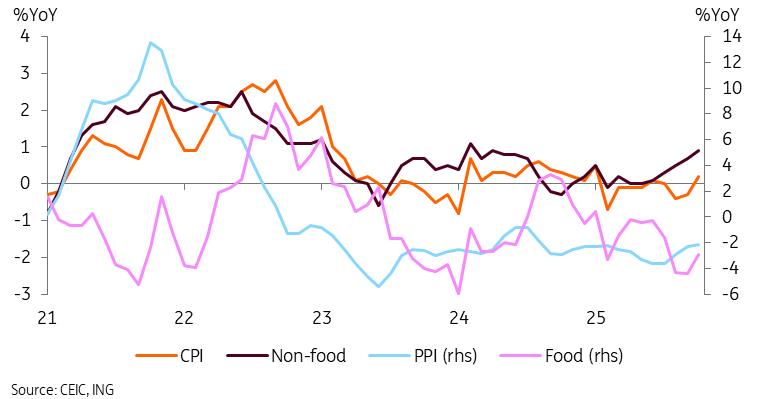

China has been struggling with deflationary pressures for the past few years. China's key indicators, such as the CPI, PPI, and GDP deflator, have all pointed to outright deflation this year.

The biggest issue has been the formation of a negative feedback loop from China's cost-cutting environment. Structural causes are at the root of this, but cyclical policies also contribute to the problem. Overcapacity has led to aggressive price wars and weak profit growth. Weak profitability has in turn led to cost-cutting, wage cuts and layoffs. This fed into weaker household confidence, higher savings, and softer domestic demand, which, in turn, worsened overcapacity.

Other factors playing into this dynamic include the property downturn, which creates a negative wealth effect, flatlining rental growth and the government's drive for“belt tightening”. This included widespread pay cuts and pay caps, which heavily dented confidence and reduced dynamism. China's trade-in policy, which helped boost consumption over the past year, may also have contributed to downward price pressures by discounting popular consumer products.

Many of the above issues will likely remain challenges in the coming years. China's anti-involution drive, where the government will start to crack down on excessive and destructive price competition, could eventually set inflation on a healthier trajectory. But we expect this process to be gradual, given the potential implications on local economies and employment.

For 2026, we could see prices edge back into positive territory, at least for CPI inflation. Quietly amid deflation headlines, core CPI has trended upward for six straight months since May, recovering to 1.2% YoY by October. In the past few months, food prices have been the big drag. This is cyclical, and the worst of these pressures look likely to fade in the year ahead as the pork cycle turns. Our view is that CPI will recover to 0.9% YoY in 2026.

Various inflation indicators have been on an uptick

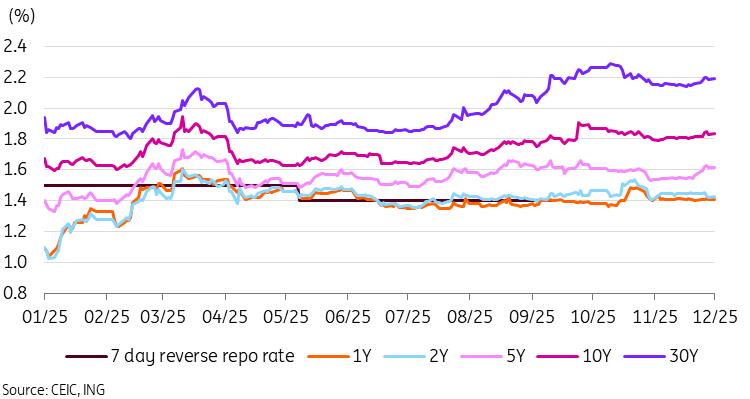

Is the PBoC already at its limit for easing?

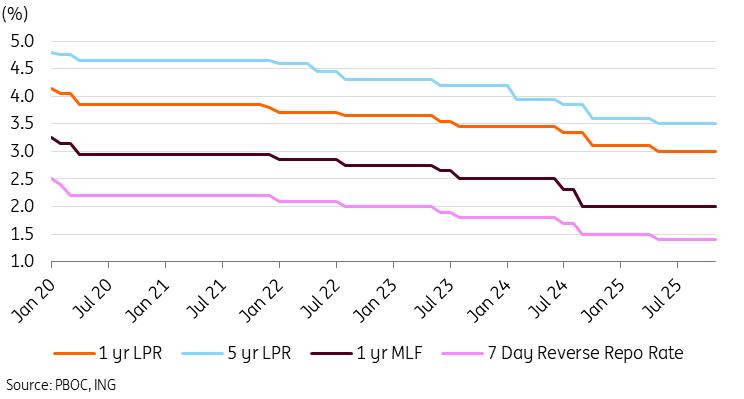

The People's Bank of China was more cautious than expected in 2025, with only one major easing move in May to cut rates and the required reserve ratio for banks.

The limited easing can be explained by three primary factors, each with varying degrees of persuasiveness:

-

First, the economy held up better than expected for much of the year. With the 2025 growth target looking on track despite recent data slowdowns, there has been limited urgency for PBoC easing in the second half of the year. As nominal rates are already low, the PBoC may not wish to enter the zero-interest-rate zone that many developed markets did after the Global Financial Crisis. As such, the PBoC has been cautious in how it uses its ammunition, opting for smaller and slower rate cuts.

Second, Chinese bank net interest margins continued to narrow, squeezing profitability. One of the more compelling arguments against further easing was that rate cuts could worsen the pressure on banks.

Third, Chinese equity markets continued to rally in 2025. While the CSI 300 and Hang Seng Index continued to trade below historical valuations, the Shanghai Composite valuations began to look a little stretched, prompting some market participants to warn against fuelling a bubble.

We expect the PBoC will remain on an easing trajectory next year despite these factors:

-

The slowdown of the past few months shows that policy will need to remain supportive to secure another year of stable growth. This will especially be the case if we see external demand soften next year.

As we covered in the previous question, deflationary pressures will remain. Even if inflation returns to positive territory, it will likely remain quite tepid. While nominal rates look low, real rates remain too high, leading to a contraction in new RMB loans.

The property market continues to turn downward, and while rate cuts are not a cure-all, lower mortgages could help improve affordability and at least alleviate the pain.

We are currently looking for 20bp of rate cuts and 100bp of RRR cuts next year, and continued targeted support for areas of focus such as services and tech development via relending programmes.

PBoC ammunition may be limited but easing should continue in 2026

What's in store for the CNY next year?

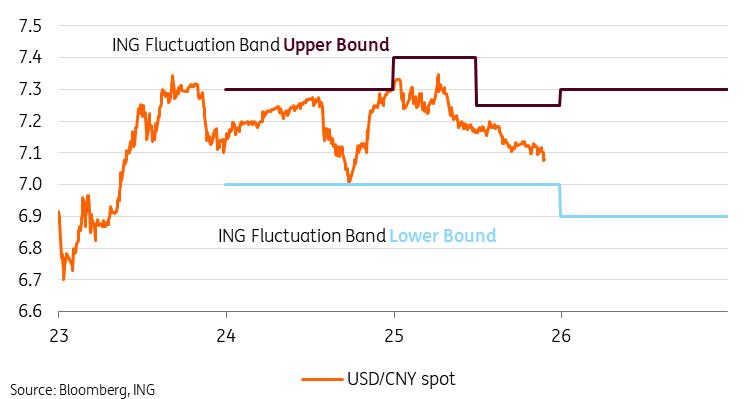

The ING call that received the most pushback by far from last year's outlook was our view that the PBoC would hold the line on the yuan for a USD/CNY fluctuation band of 7.00-7.40. This time last year, the call was controversial, with many market voices expecting depreciation to support exporters ahead of a second trade war.

As it became clear that the PBoC was not only willing but also able to maintain its currency-stability stance, the range held. Our call gradually moved from outlier to consensus.

At this juncture, we see little reason to change the call for limited fluctuation in 2026. Currency stability has worked out well for China in the past few years:

-

A stable CNY helped avoid another area of uncertainty and avoided outflow pressures at a time when sentiment was already vulnerable.

It also provided a predictable environment to support outward direct investment, which rose 4% YoY through the first three quarters of the year despite a contraction of fixed asset investment domestically.

The tariff escalations showed that intentional depreciation likely would've been akin to throwing a bucket of water at a blazing inferno. A 10% or 20% devaluation would have done little to offset tariffs, which had surged to 145%. It likely would've prompted complaints of currency manipulation.

We expect the fluctuation band to edge down to 6.90-7.30 next year as the PBoC continues to keep a lid on volatility. Our 2026 year-end forecast for USD/CNY is 7.00, though we think this 7.00 level could be tested earlier in the year.

We view risks to our forecast over the next year as balanced toward CNY appreciation, given the narrowing US-China yield spread and the large amounts of FX held abroad by Chinese exporters that have yet to be converted back to China. If the positive momentum from the past year continues, further recovery of risk appetite and foreign investor net inflows would support the CNY. Depreciation risks could be tied to risk events that intensify capital outflow pressures and a risk-off sentiment domestically, bringing Chinese interest rates lower and widening the yield spread once more. A more hawkish-than-expected Federal Reserve and a stronger US dollar backdrop could be risks for the USD/CNY moving higher as well.

The biggest risk to our forecast band would be a pivot away from the currency stabilisation priority. Without the PBoC's use of the countercyclical factor in its fixings, we'd likely see a lot more volatility. We see no signs of this at the moment, but it cannot be ruled out if priorities shift.

Our USD/CNY fluctuation band forecast shifts lower for 2026

Could CGBs be next year's big surprise?

Our view on Chinese government bonds (CGBs) looks to be one of our more non-consensus calls for the 2026 outlook. At the time of writing, we seem to be the only house expecting an uptick in CGB yields next year. Markets are expecting 10-year yields to slide to 1.58% by the end of 2026, which would mark a new historical low, while we see room for yields to move higher to 2%.

Our view is that yields have been suppressed by several overlapping factors:

-

First, this has been a period of excessive pessimism on China, leading to portfolio rebalancing from risk assets to bonds.

Second, longer-term deflation expectations have strengthened, reducing the inflation premium.

Third, borrowing demand has been weak, while banks have seen new liquidity due to RRR cuts, leading them to invest excess liquidity in the CGB market.

An interesting feature of the CGB market over the past few years: no matter the market's actual direction, the surrounding discourse tends to be skewed negative. When yields drop,“Japanisation” doom and gloom permeates the market. When yields rise, we often see headlines of“bond market routs”.

Taking things into perspective, the CGB market remains well-supported, with yields well below the levels typically associated with an economy growing 4-5% per annum.

We believe that a further uptick of 10-year yields to around 2% could be a natural consequence of continued risk appetite normalisation. Despite the equity market rally of the past year, there could still be room to run, given the overall depressed economic confidence indicators and the fact that no major Chinese equity index has returned to all-time highs yet. Furthermore, bond issuance will likely need to remain high given the need for fiscal support next year.

Continued risk appetite normalisation could see yields rise further

10 What are the key economic issues as the 15th Five-Year Plan begins?

A draft of the 15th Five-Year Plan was made available soon after the Fourth Plenum in October. The draft is to be finalised in the coming months and approved at the Two Sessions in March, but the key themes are likely already set.

The first question laid out in this report addressed the importance of getting 2026 off to a good start to secure medium and long-term growth targets. The FYP also outlines China's priorities for the future.

First, despite talk of cutting overcapacity in the anti-involution drive, it's clear that China has no intention of giving up its manufacturing dominance. One glaring takeaway from the FYP is that the section on industrial modernisation became the first main focus, surpassing innovation. The emphasis on upgrading traditional manufacturing while leaning on advanced manufacturing as the economic backbone aligns with China's big-picture transition up the value-added ladder.

Second, despite moving down one peg, innovation remains a key goal and is expected to create more of the so-called“new quality productive forces” to drive future growth. Key themes include continuing digitalisation and supporting AI+, which will be centred on bringing AI products to market. Tech self-reliance also featured prominently, indicating that China will continue to invest in building domestic capabilities in semiconductors, AI, and related strategic sectors.

Third, domestic demand remained in the third slot, with the messaging tone remaining positive. The FYP mentioned that an“implementation of special actions” was needed to boost consumption. This strongly hints at new support ahead, following the trade-in policies of recent years. It hasn't yet specified what this might look like. We suspect that, given the concurrent focus on supporting service sector development, moves to boost consumption could target services spending, potentially via consumption vouchers.

The section on domestic demand also brought up developing more cities into international consumption centres and expanding inbound consumption. This suggests ramping up consumer imports moving forward, which represents new opportunities for China's trading partners to tap into a growing middle class.

In terms of investment, the pivot from quantity to quality is set to continue, with the government seeking to optimise investment and reform the government approval system. This aligns with the anti-involution push, where China wants less redundant and more synergistic investment to align with a national, rather than regional, development strategy.

China remains in the process of a Great Transition. This means moving toward a more domestic demand-driven growth model, up the value-added ladder and hastening green and tech transitions that will shape China's long-term economic future. The 15th FYP strategically stays the course on most of these major transitions. In 2026, it will become clearer how the government plans to execute this in practice.

Hi-tech manufacturing will be core to China's growth strategy

Conclusion: China aims to get 15th five-year period off to a strong start

There are arguably three certainties in life: death, taxes, and economists talking about uncertainty in their annual outlooks. Every year's outlook write-up is often an exercise in swapping out old uncertainties for new ones.

The magnitude and expected impact of tariffs on Chinese growth were probably the biggest sources of uncertainty in 2025. Given a trade truce tentatively set to last at least until 4Q26 and China's export resilience, the tariff outlook remains a key, but less pressing issue. Instead, the focus is on whether external demand from the rest of the world holds up.

Arguably, the bigger questions for next year will be on domestic policy. They include how aggressive policymakers will be in providing fresh stimulus and how China will implement plans to boost domestic demand. Recent policy has been effective in front-loading demand, but the impact is fading, and confidence remains low. Fixed-asset investment growth has fallen into contractionary territory. The property market slide is accelerating. While 2025 looks likely to meet the year's growth targets, these factors represent significant question marks for 2026, especially if external demand slows more than anticipated.

With longer-term targets for 2030 and 2035 already set, getting the economy off to a good start in 2026 will be key to achieving these targets.

Our forecasts for China

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the

information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept

any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images,

videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information

contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright

issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Comments

No comment