Global Learning Can Help Kashmir Break Old Patterns

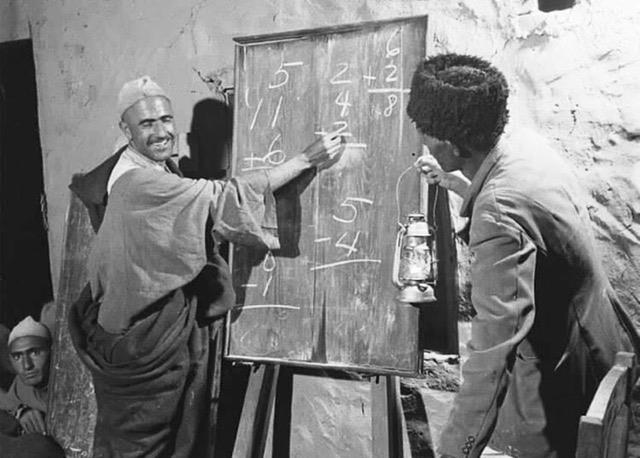

Representational Photo

By Dr Muzamil Sultan

Too often, people in Kashmir follow the crowd, moving along familiar paths without questioning them.

Superficial concerns, ego, envy, and an obsession with status shape much of everyday life.

ADVERTISEMENTGossip spreads easily, personal gain often comes before the common good, and narrow, tribal thinking blocks fresh ideas.

When careers, institutions, and ambitions are driven more by competition and self-interest than by purpose or ethics, it's hard for any society to truly move forward.

The problem goes even deeper.

Social pressures and hidden cultural shifts shape the way we think, often without us realizing it.

Over time, this erodes our sense of right and wrong, creating patterns that weaken communities instead of helping them grow.

Even many white-collar professionals are guided more by comparison than by true purpose.

If a cousin or neighbour becomes a doctor, others feel pressure to follow the same path, simply to keep up or prove themselves.

In the process, even careers meant to serve others can lose their meaning. They shift from contribution into competition and from service into status.

A similar pattern shows up in the growing interest among young Kashmiris in civil services, which is an admirable ambition on the surface. But when asked about their goals, many focus more on the appeal of authority, privileges, and social recognition than on improving education, making policies effective, or serving the community.

This reveals a mindset that puts personal gain above civic duty.

When status, comparison, and ego drive choices, every part of society reflects it. Politics, bureaucracy, healthcare, and education all start to mirror the same motivations.

Over time, individual ambitions shape institutions, and those institutions, in turn, reinforce the same ambitions. A self-perpetuating cycle forms, where personal gain overshadows collective purpose, and this mindset becomes woven into the social fabric.

The same mindset shows up when we look at how society values different professions.

Take a waiter, for example. Many see his work as“lesser,” but he earns his living honestly, without exploiting anyone, bending rules, or pretending to be someone he is not.

In many ways, he shows more integrity than people in prestigious jobs who fail to live up to the ethics those roles demand.

The problem grows when white-collar professionals, armed with degrees but lacking humility, assume they are inherently superior.

This reveals a deeper misunderstanding of what education truly means.

Beyond collecting degrees or qualifications, education is essentially about shaping wise character. A truly educated person sees dignity in all honest work, whether someone is serving a meal or performing a complex surgery.

This difference is clearer in societies where respect, not hierarchy, shapes social life.

In many European countries, strong ethical standards are the result of centuries of cultural traditions, accountable institutions, and shared moral expectations.

Morality is part of everyday life in West. Politicians and civil servants go about their routines with ease and simplicity. It's normal to see a minister standing in line at a supermarket, carrying their own groceries, cycling to work, or taking the metro without security.

These actions aren't celebrated because they're expected. Public office doesn't put anyone above ordinary life.

In these societies, power is stripped of spectacle. Leaders who demand special treatment or show entitlement are seen as unfit.

Authority is not a personal advantage, and public trust depends on humility and restraint.

European politicians aren't from another world. Their behavior reflects the values of the society that shaped them.

In contrast, in much of South Asia, politicians and bureaucrats often seem out of touch. They rise from systems where ethical standards are weak, and this shapes the kind of governance people actually experience.

This same moral framework helps explain why resignations over seemingly small ethical breaches are treated as normal rather than shocking events.

In Germany, Health Minister Ulla Schmidt faced a national controversy simply for using her official limousine during a private vacation in Spain, a breach of public trust that damaged her credibility.

State Secretary Thomas Mirow resigned after accepting discounted airline tickets linked to corporate interests.

In Ireland, ministers such as Beverly Flynn, Ivor Callely, and Michael Lowry stepped down over improper phone expenses, undeclared payments, or small preferential deals, issues that in other countries might have been dismissed as trivial.

In the United Kingdom, more than twenty MPs and Lords lost their positions for claiming public money for household cleaning, gardening, furniture, or even maintaining a decorative moat.

The amounts were often modest, but the expectation of integrity was so high that even minor breaches ended careers.

Taken together, these examples reveal a deeper truth about Europe: ethical conduct is a social obligation enforced by the public conscience.

In these societies, the moral compass of the community values humility, transparency, and self-restraint.

Dignity is measured by one's commitment to fairness, honesty, and civic responsibility. Ethical behaviour is an internal guide shaped by values passed down through generations.

European social ethics grow from a culture where hierarchy is intentionally softened so equality can thrive.

A teacher, a nurse, a bus driver, or a minister are all seen through the lens of what they contribute. Respect comes from recognizing human worth, rather than job titles. Even professions like medicine, civil service, or engineering are valued for service than status.

The absence of a superiority complex keeps society from falling into competition-driven vanity.

This mindset also makes arrogance easy to spot as a moral failure. Ego is seen as a barrier to reason, and domination is seen as a threat to the collective good.

A leader who acts overly powerful only exposes insecurity. A civil servant who rules like a king instantly loses legitimacy.

Ethical consciousness in these societies is both personal and institutional.

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the

information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept

any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images,

videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information

contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright

issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Comments

No comment