Canada's Rising Poverty And Food Insecurity Have Deep Structural Origins

According to a 2024 report by the federal government's National Advisory Council on Poverty, poverty is also on the rise , and people who once thought they were financially secure are starting to feel the squeeze .

Canada is a signatory to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, recognizing the right to food, housing and an adequate standard of living.

As a social scientist, my research shows that Canada is struggling to realize these rights because decision-makers often lack the political will to act, and the judicial system still relies on an outdated approach that cannot hold these decision-makers accountable.

Understanding the rights splitHuman rights are indivisible, meaning they're all equally important and interdependent: one right cannot be realized without realizing the others . To meet their commitments, signatory states have agreed to respect, protect and fulfil human rights and to use the“maximum available resources” at their disposal to progressively achieve them .

While Canada and other United Nations member states have endorsed social and economic rights, these rights have often been treated differently from their civil and political counterparts .

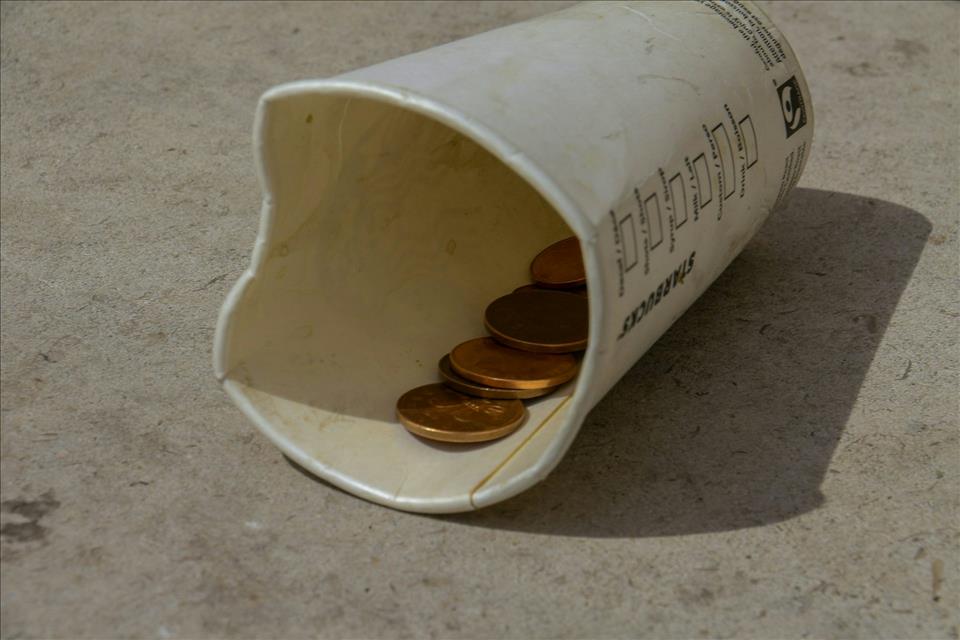

Though Canada is a signatory to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, too many people are struggling to put food on the table. (Unsplash)

Civil and political rights are typically considered negative rights , which do not require the government to act or provide anything, but rather to protect or not interfere with people's rights, such as freedom of expression or religion. Social and economic rights, on the other hand, have often been deemed positive rights , meaning they require the state to act or provide resources to meet them, like education or health care.

In 1966, human rights were split: civil and political rights were placed under one covenant , and economic, social and cultural rights under another , rather than having them all affirmed under one, as was originally envisaged in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948.

Weaker language was deliberately included in the International Covenant of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights by the rights architects, particularly those in the United States, who felt that its ratification should not encroach on state autonomy or require “thicker social programs and a robust welfare state.”

Consequently, the courts, particularly Canadian lower courts and others internationally , have over the years commonly affirmed that social and economic rights are policy matters best determined by political entities and given democratic legitimacy at the ballot box.

While there is overlap between the two sets of rights , social and economic rights have frequently been deemed non-justiciable - not something people can challenge in court - and therefore not ones people can directly claim or pursue legal remedies for. Instead these rights have taken on an aspirational quality .

When courts are reluctantGosselin v. Québec set an important precedent for how social and economic rights would come to be interpreted in Canada.

This case relates to a regulation in the 1980s that set Québec's social assistance benefits for people under 30 at only two-thirds of the regular benefit ($170 rather than $466 per month). The plaintiff claimed that the regulation was age-discriminatory and violated the Québec and Canadian Charters of Rights and Freedoms under Sections 7 and 15 .

Judges in Québec, and later in 2002 in the Supreme Court - although the justices were split on the decision - confirmed the Charter did not impose positive-rights duties on governments, even while the Supreme Court left the door open that it could do so in the future .

Yet some legal scholars contend that the case took constitutional law“two steps backward” and failed to debunk the prejudicial stereotypes surrounding people living in poverty that influenced the decision. In 1992, a Québec Superior Court judge said“the poor were poor for intrinsic reasons” - that they were under-educated and had a weak work ethic.

Such reasoning, however, reflects an individual explanation of poverty - that financial hardship derives from personal failings or deficits - rather than a structural one, where poverty stems from economic downturns, weak labour markets and a lack of affordable child care or housing .

A significant body of evidence now shows that poverty largely has structural origins . Although there have been some victories on social and economic rights, many cases have followed the interpretation in Gosselin.

The right to housing was explicitly identified in the 2019 National Housing Strategy Act . The act introduced the National Housing Council and a complaints and monitoring mechanism through the federal housing advocate , a model that limits people from demanding state-provided housing and suing if they don't receive it.

Lacking an ecosystem of rights compliance and enforcement, governments have turned to less effective options like charity, rather than engaging solutions that could actually end poverty and hunger, such as a basic income guarantee .

The impasse on social and economic rights has led to the denial of these rights for those living in poverty.

Enforcing implemented rightsSome, like Oxford legal scholar Sandra Fredman, argue the courts should use legal frameworks not to defer to politicians or usurp their decision-making capacity, but to require them to provide reasoned justifications for their distributive decisions.

Although non-binding, the UN's judicial body, the International Court of Justice , recently concluded that countries have legal obligations to curb their emissions. Some courts, domestically and globally, are also gravitating toward the enforcement and justiciability of human rights , particularly in climate-related cases and the right to a healthy environment .

These could provide new precedents that transform how these rights are understood and enforced in the future.

Without concrete resources, targets and accountability mechanisms to ensure people have dignified access to food, housing and social security, these rights will remain largely hollow.

The “climate of the era” has changed. It's time for politicians to actively work to fulfill social and economic rights and for the courts to hold them accountable when they fail to do so.

Without substantive rights - ones backed by action - poverty will continue to rise and people will be denied justice.

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the

information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept

any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images,

videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information

contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright

issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Comments

No comment