(MENAFN- Asia Times)

TEHRAN – For a nation under the crush of international sanctions, membership in the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) was never just about diplomatic photo-ops. For Iran, it was pitched as a strategic pivot – a litmus test of its economic viability beyond the Western financial system.

The objectives were clear and pragmatic: first, to forge an alternative financial channel to bypass the US dollar and banking sanctions; second, to attract vital capital for strategic infrastructure projects.

Years after its full accession, as the dust settles on another summit, it is time to audit the books. Did Iran achieve its core economic goals? The balance sheet so far delivers a stark verdict.

De-dollarization mirage

The banner cause of SCO economic summits has consistently been the ambitious goal of“de-dollarization” and trading in national currencies. For Tehran, this was framed as a lifeline for its isolated banking sector. A closer inspection, however, reveals a harsh reality.

The SCO still lacks a unified financial messaging system (a SWIFT alternative) or a multilateral clearing house to settle complex trades. Existing agreements are largely bilateral and ill-suited for a non-convertible currency like the Iranian rial.

Moreover, the de-dollarization initiative is not creating a democratic basket of currencies; it is paving the way for the gradual hegemony of the Chinese yuan. In practice, the roadmap for using local currencies has remained a political statement, not a functional economic tool for Iran.

A post-mortem on stalled megaprojects

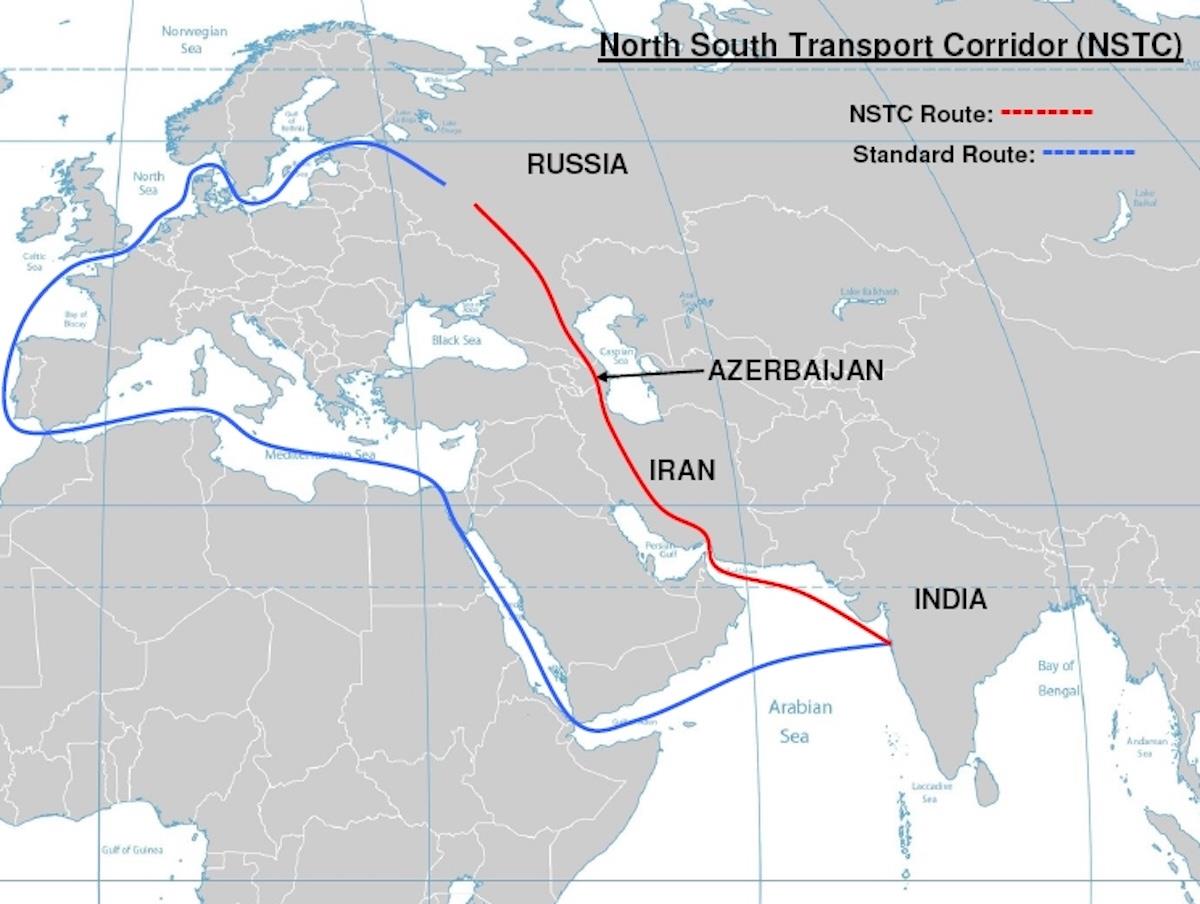

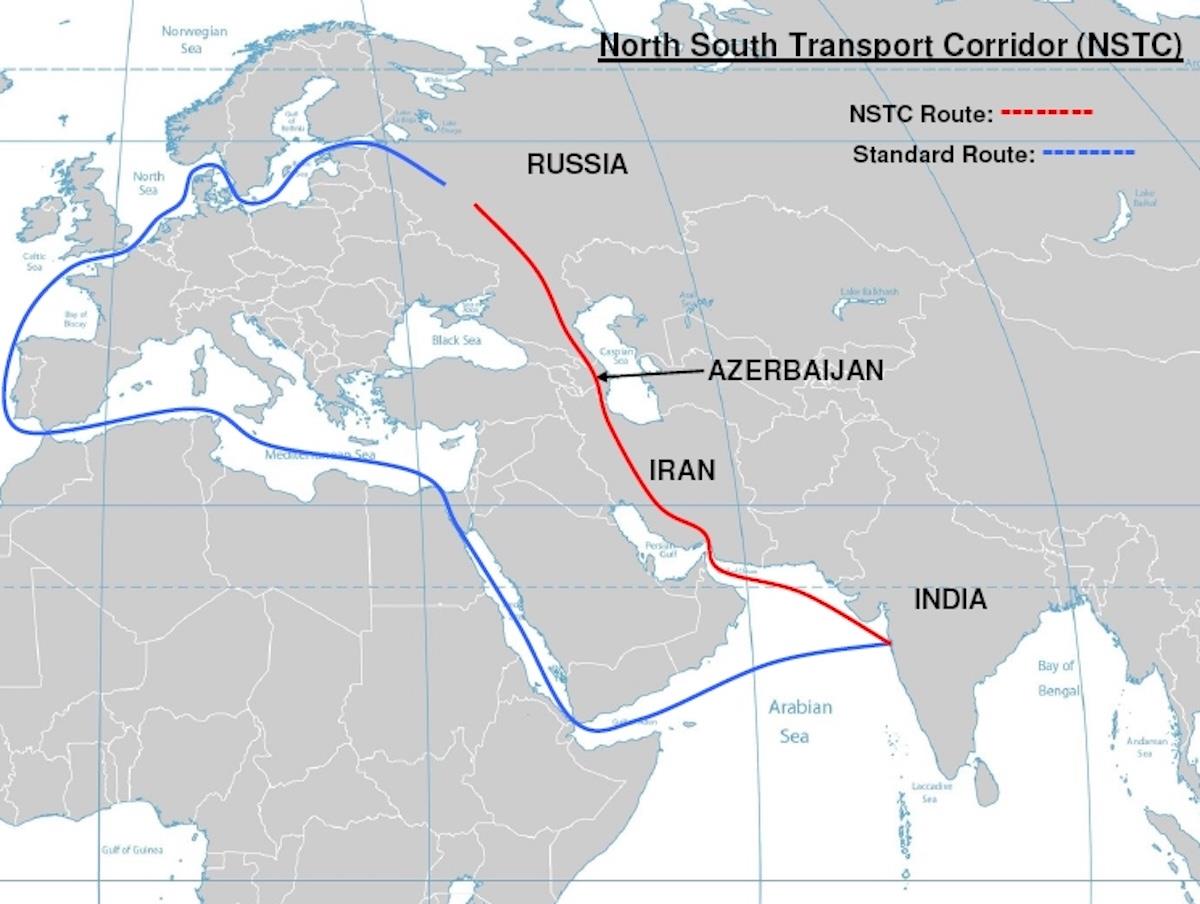

Iran's primary economic showcase at the SCO has been the International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC), a project meant to connect Russia to the Indian Ocean. The expectation was that the SCO's political umbrella would unlock the financing needed to complete it. The table below tells a different story.

Map: Wikipedia

Table 1: Reality Check on Key International Rail Corridor Segments (Iran portion)

MENAFN04092025000159011032ID1110016440

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the

information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept

any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images,

videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information

contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright

issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Comments

No comment