America Is Having Its Ming Dynasty Moment

Ten years ago, when I was still writing freelance articles in my spare time, I wrote a post for The Week in which I mused about America becoming like China's Ming Dynasty - powerful but insular, rich but stagnant, arrogantly disdainful of science and technology, and ignorant of progress being made in the world outside:

At the time, this post was not particularly well-received. Experts on Chinese history scoffed at the analogy and told me to stay in my lane. The broader public simply yawned, seemingly secure in the belief that America would continue to be the world's leading nation, as it had been for their entire lives.

I agree that sweeping historical analogies are overwrought and rarely useful, especially when they draw parallels between modern times and the agricultural age. To be honest, at the time, I wanted the post to be more of a warning than a prediction.

I didn't think the US was well on its way to becoming the Ming dynasty, but I saw a few troubling signs of complacency and insularity, and I wanted Americans to be more proactive about fixing our country's problems and pushing progress forward. We have a long and hallowed tradition of using declinist histrionics as a form of self-motivation.

These days, however, I often find myself thinking about that post, and it feels like the Ming analogy fits a bit better than it did in 2015. I thought about it again when I saw the results of a recent Ipsos poll , which asked countries around the world about their attitudes toward AI. Of all the countries surveyed, Americans were among the most negative toward the technology, and Chinese people were among the most positive:

Source: Ipsos

This survey closely parallels my own experience. When I hear other Americans talk about AI, it's usually disapprovingly - many seem to think of AI as primarily something that threatens their jobs while producing little that they need or want. Over on X, I decided to see what would happen if I expressed bland, anodyne, positive sentiments about AI:

Here were some of the representative responses that I got:

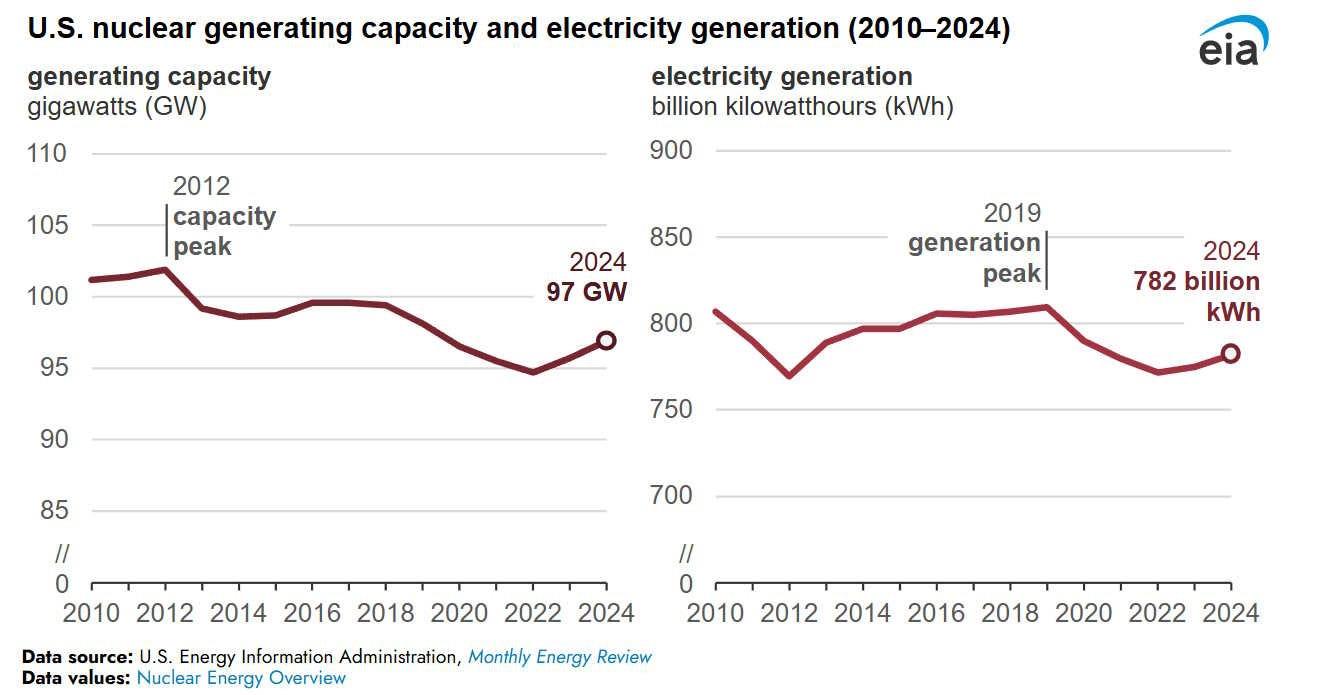

It's not just AI, though. Look at the two countries' different approaches to nuclear power. Over the past decade, China has nearly tripled its nuclear capacity, while America's has declined:

Source: EIA

Source: EIA

And this divergence is accelerating. China just approved 10 new nuclear plants , which will catapult it past the US and France to be the world's top country in nuclear energy. Meanwhile, in the US, the Republicans in the House of Representatives are poised to wreck the domestic nuclear industry. Thomas Hochman and Pavan Venkatakrishnan write :

I don't think nuclear will be our most important energy technology over the next half century, but this is still a very bad sign.

Why do Americans fear the future while Chinese people embrace it?Why are Americans so much more negative about AI and nuclear power than Chinese people? We're always tempted to blame partisan ideology, and I admit that sometimes that is the root of the problem (see, for instance, mRNA vaccines). In general, there's a recent pattern where Democrats fear the software industry while Republicans are apprehensive about new physical technologies.

But in these cases, I just don't think that explanation fits. Nuclear power is traditionally thought of as being Republican-coded, and yet this time it's Republicans who are now voting to gut it. And fear of AI is very bipartisan :

Source: AI Policy Institute

The most likely reason, I think, comes from the two countries' recent histories. We know that people's life experiences deeply shape their macroeconomic expectations ; why should attitudes toward technology and progress be any different?

The US has been a slow-growing country at the technological frontier for as long as almost all of us have been alive. If your country generally grows at 2%, you can expect to see your living standards quadruple over your lifetime. That's much better than nothing, but it means that in the shorter term - over a five-year or ten-year period - your economic fortunes will be primarily determined by random shocks, not by the slow and steady march of technological improvement.

A spell of unemployment, a medical bankruptcy, a decline in the price of your house, the loss of a government contract or a big customer - any of these could wipe out many years of slow improvement in living standards.

In other words, to most Americans, risks loom larger than opportunities. If everything stays the same, then they'll continue to be wealthy and comfortable; if something changes, they might not. In an environment like that, it makes sense to be afraid of change, because change means risk.

For most of Americans' lives, technological progress has been a major source of risk. The advent of the internet put encyclopedia salesmen and term life insurance salesmen out of a job. Hybrid cars from Japan put competitive pressure on traditional carmakers.

Flip-phone makers were wiped out by smartphones. Electronic trading made many human“specialists” obsolete. And so on and so forth, throughout the economy. At the aggregate level, these innovations drove growth in living standards, but at an individual level, having the technology in your industry change was generally a source of peril.

Someone who grew up in modern China has experienced something utterly different. Over the course of their lifetime, rapid technological progress has radically transformed their lives and the lives of the people around them, allowing them to experience a level of comfort and security utterly undreamt of by their grandparents.

Meanwhile, the risks from new technology were pretty low. In a fast-growing economy, if your job gets automated, you can often just go get a better one. If your industry gets destroyed by competition from a new technology, you can often just go work for the winners, since everyone is just expanding business so quickly.

You can see this pattern in all sorts of polls. A decade ago, Pew did a survey and found that fast-growing countries tend to be much more optimistic about the future than slow-growing ones:

Source: Pew

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the

information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept

any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images,

videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information

contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright

issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Comments

No comment