Northern Syria and the Problem It Provokes in Turkish-American Relations | Syndication Bureau

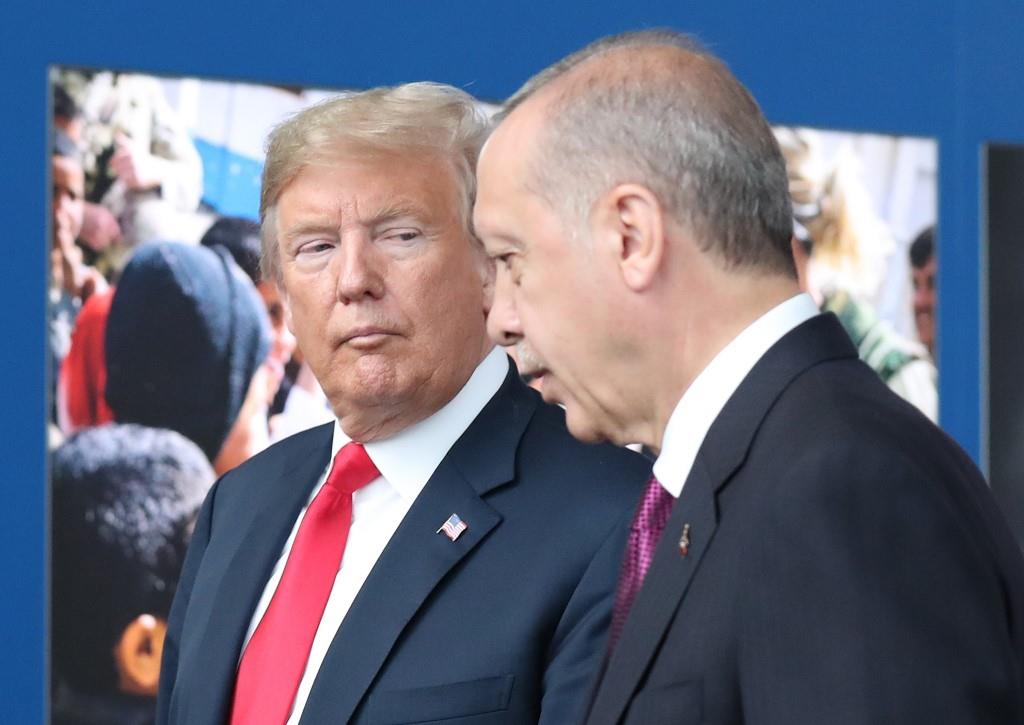

Decades from now, history books dissecting what went wrong in Turkish-American relations will dedicate a special chapter to Syria. Before the civil war in in that country, Ankara and Washington could still pretend to be strategic partners, despite significant problems between the two. But the uprising in Syria has not only turned the autocracy into a failed state, it has also made Turkish and American armed forces regard each other as quasi-enemies.

Almost all the current problems in Turkish-American relations, ranging from American military support for the Kurds to Turkey's purchase of a Russian missile-defense systems, have their roots in Syria. And make no mistake, it will take much more than the recent cosmetic agreement between Ankara and Washington to establish a“joint operating center,” to reconcile their profound differences about what to do in northern Syria.

The reason is simple: the safe zone that Americans want to establish is to protect the Kurds from Turkey, whereas the safe zone that Turkey has in mind is one that will protect itself from Kurdish terrorism. Good luck solving this problem with a joint operation center.

When there are such fundamental differences in threat perception, all that such an agreement can hope to achieve is to delay the inevitable: a Turkish military incursion to destroy America's Kurdish partners east of the Euphrates river. Turkey has already achieved this very goal in northwestern Syria, thanks to Russia turning a blind eye to the Turkish military presence in Afrin. For President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, the price of this military foray into a Russian zone of influence was the purchase of the S-400s. Vladimir Putin has the upper hand in this region and he has played it cleverly by not only luring Turkey further away from Washington, but also weakening Nato's entire military architecture. All of this unraveling comes courtesy of the Syrian quagmire.

To be sure, there were already significant problems in Turkish-American relations before the Syrian war. In fact, it was soon after the Cold War and particularly after the 9/11 terrorist attacks that major differences in threat perception emerged between Ankara and Washington. Terrorism proved to be a poor substitute for the Soviet threat. The problems began as jihadism replaced communism as the existential threat in the eyes of America, the superpower. Turkey also had its problems with radical Islamists, but the threat for Ankara was terrorism with ethnic Kurdish rather than jihadist roots. And as the Middle East became the new center of gravity for the bilateral agenda, things went from bad to worse; not only the Kurdish question, but also the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, the role of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt – all poisoned the relationship between the Nato allies, Turkey and the US.

They found themselves on opposite sides when debating how to deal with Hamas or the military coup in Egypt, where Ankara believed Washington was complicit in the bloody coup that eradicated a democratically elected Islamist movement. A Middle East dominated by the Muslim Brotherhood was the ultimate dream of Erdogan, who fancied himself as the neo-Ottoman architect of a new order in the Arab world. With the ousting of Mohammed Morsi, this Turkish dream – seemingly within reach after Islamist electoral victories in Tunisia and Egypt – turned into a nightmare. And the Turkish strongman blamed Washington even more than regional actors such as Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates for this state of affairs.

None of these challenges, however, presented vital national security threats for Turkey or the US and the strategic partnership seemed to survive, at least on paper. It was with the Syrian civil war that compartmentalization in Turkish-American relations rapidly reached its limits.

The Syrian uprising changed everything. ISIS, after all, was largely a product of state collapse in Syria. The American decision to arm Syrian Kurds linked to the Kurdistan Workers' Party, or PKK, to counter this jihadist threat came as a shock to the Turkish national security establishment. In Ankara's eyes, Washington was arming a terrorist organization – its Kurdish nemesis – in the name of fighting another terrorist entity. Washington, on the other hand, had its own axe to grind. To the American military, it looked like Turkey was in bed with radical Islamist groups linked to Al Qaeda and was turning a blind eye to ISIS supporters entering Syria over its porous border with the country.

All this did not bode well for maintaining a strategic partnership between two Nato allies. Having different threat perceptions was tolerable to a certain degree. But now Ankara and Washington were each supplying military aid to the other's existential threat. And it proved too much to stomach for what was left of a partnership that had always depended on a common threat rather than shared democratic values.

Where do we go from here? Far from restoring a once-strategic partnership, the best the two countries can now strive for is damage control and crisis management. Their new agreement on northern Syria, which was made public this month, essentially does just that. The vague language of the deal merely kicks the can down the road with a joint operation center when there is nothing joint and little to operate. This agreement does not present a common strategic vision or even a major American commitment to work with Ankara. But it is certainly better than the nightmare scenario of two armies shooting at each other in northern Syria.

Ömer Taşpınar is a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and a professor of national-security strategy at the National Defense University in Washington.

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the

information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept

any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images,

videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information

contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright

issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Comments

No comment