Bruce Pascoe's Black Duck Is A 'Healing And Necessary' Account Of A Year On His Farm, Following A Difficult Decade After Dark Emu

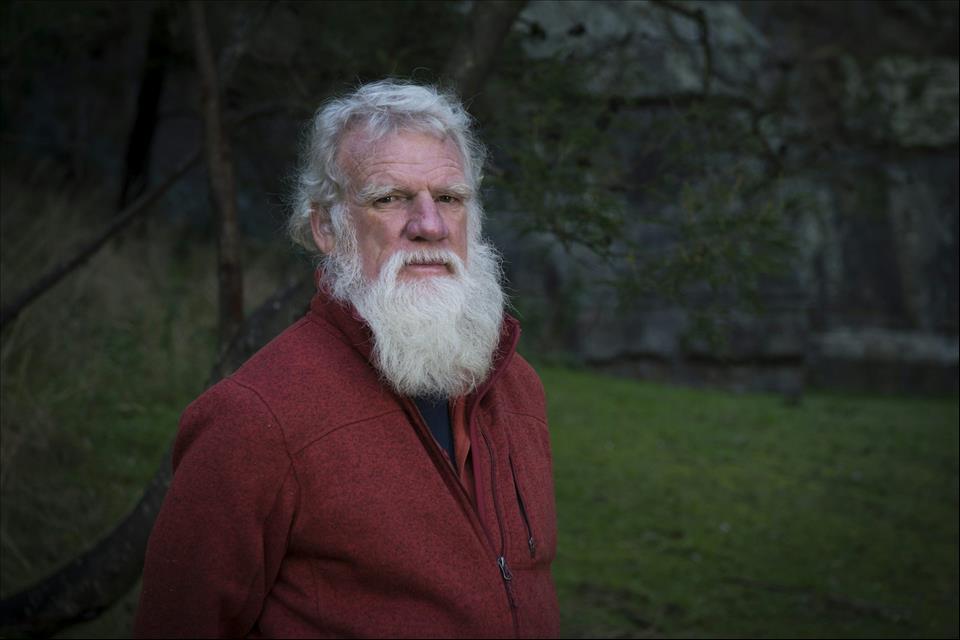

Since the publication of Dark Emu in 2014, Pascoe has had to endure extraordinary public scrutiny, as well as vehement attacks on his personal and professional reputation.

Those who envy Pascoe's runaway sales figures would surely not covet the scale of the personal attacks launched against him, primarily (but not wholly ) led by right-wing critics who read the arguments laid out in Dark Emu as an opportunity to reignite Australia's History Wars .

Review: Black Duck: A Year at Yumburra – Bruce Pascoe with Lyn Harwood (Thames & Hudson)

The Dark Emu controversy, writes Pascoe, tested his relationship with longtime partner Lyn Harwood, his co-author on this book,“to the limit”. He writes:“It came to a point where she could barely sit in the room when some stranger came to discuss the bloody emu.” They eventually split in 2017, three years after Dark Emu was published, while remaining“best friends and supporters”. They reunited in 2021, though they still live in separate houses.

In the recent full-length documentary The Dark Emu Story (2023), Pascoe appears as a frail and aged figure, tired out and depleted by the heat of a decade's struggle against hatred and racist vitriol.

Bruce Pascoe's Dark Emu sold at least 360,000 copies – but he also had to endure extraordinary personal attacks. Lyn Harwood/Thames & Hudson

In light of the last ten years, Black Duck: A Year at Yumburra is a healing and necessary book.

Yumburra is the name of Pascoe's farm on the banks of the Wallagaraugh River, in Yuin country in far east Gippsland, purchased and established with the funds raised from selling an old house and income earned from his book sales.

It's been transformed into a social enterprise, Black Duck Foods (supported by the Two Fold Bay Aboriginal Corporation, Native Foodways and the University of Melbourne, among others).

The farm is a deliberate project designed to test, extend and materialise some of the ideas put forward in Dark Emu. In particular, it is Pascoe's attempt to bring to life a vision for growing traditional food on Country in a manner that benefits both the land and Aboriginal people.

The meaning of Yumburra, Pascoe tells us, is Black Duck, the“supreme spiritual being of Yuin country”. This book is“the story of a year in her company”.

Read more: Dark Emu has sold over 250,000 copies – but its value can't be measured in money alone

Six seasons on the farmThe book is organised according to the six Yuin seasons over a single calendar year, beginning with late summer (early in the new year of 2022) and finishing with the early summer season (close to Christmas). Through more than 60 subtitled journal entries, accompanied by numerous photographs and sketches, Pascoe charts the activities of his days.

These include labouring chores on the farm, visits paid and received (both there and interstate), thoughts, visions and experiments with food and agriculture, and memories and reflections on relationships reaching far back into childhood.

Pascoe describes life on the farm as solitary at times, but also active. Daily farm work includes clearing watercourses or fixing tools and machinery, and at these times his friendships with the nonhuman are forged in both subtle and overt ways.

He acts as silent witness to the aggressive tactics of the Garramagang (magpie) aimed at other resident birds, for example. And he puts his verandah light on during the cooler weather to help warm the small birds who have been nesting there seasonally for years:

Bruce Pascoe writes about his 'nonhuman friendships' with animals like Bunjil, the wedge-tailed eagle. Lyn Harwood/Thames & Hudson

In fact, birds, and other forms of wildlife Pascoe observes at Yumburra, dominate the journal entries – and some would say, steal the book.

Many descriptive passages, sometimes accompanied with photography and illustration, document Pascoe's interactions with Birran Durran Durran (plover), Bunjil (wedge-tailed eagle), Garramagang (magpie), Yumburra (black duck), Nenak (yellow-tailed black cockatoo) and Buru (kangaroo). They are evocative and transporting.

Descriptive and evocative passages and illustrations describe Pascoe's interactions with birds, like the spur-winged plover. Lyn Harwood/Thames & Hudson

The cumulative effect of Pascoe's commentaries on his nonhuman companions – including their arrivals and departures from the farm and nearby waterways, their plays and struggles, their family dramas, births and deaths – does much to create the book's soothing, dependable rhythm. There is a sense of time moving on through the seasons. This also enables the narrator's capacity to, as Stephen Page puts it in his endorsement, get“right into the belly of the land.”

Read more: Magpies, curlews, peregrine falcons: how birds adapt to our cities, bringing wonder, joy and conflict

Because the book is set predominantly in 2022, memories of the devastating Black Summer bushfires that raged through the East Gippsland region, burning 326,000 hectares and isolating several thousand people in the town of Mallacoota (down the river from Yumburra) during the summer of 2019-20, remain fresh and vivid for Pascoe and his community.

Yumburra, too, was affected by that event, leading one of the farm workers to rename a whole section of the farm“Apocalypse Valley” in the aftermath. Pascoe's narrative turns back to that devastating fire event again and again, as he describes in moving detail his own experience of that time, and its lingering impact on himself and others.

I will long remember his description of getting lost in the smoke while steering his boat along a section of river he thought he knew like the back of his hand.“So much” has changed since those devastating fires, he writes, including his sense of smell.“The unbridled pleasure I used to take in the forest, waters and shores is now tinged with sadness and dread.”

Sun Orchids were prolific after the Black Summer bushfires. Lyn Harwood/Thames & Hudson A true storyteller

Grief also accompanies much of the writing on Gurandji lore discussed in the book, predominantly because of the death of influential senior lore man, Max Dulumunmun Harrison , Pascoe's valued mentor, just before Christmas in 2021.

Much of the 12 months to follow, as Pascoe chronicles, is dedicated to organising a Gurandji ceremony for Uncle Max, and to sorting out a way for Gurandji to approach the present and future – both individually and together – in a manner that lives up to his expectations. The author is respectfully light on detail on these matters, but the reader is left in no doubt about their deep importance to him.

Pascoe's authorial style sometimes comes across as a touch too lackadaisical and larrikin-esque, drifting as if unmoored. At points, you feel like you're captive to some bloke who has pulled up the bar stool beside you at the local pub (or in the case of ex-barmaids like me, installed himself across the counter from you during a lengthy shift).

And yet, he's a true storyteller – and no sooner have you hesitated, than he reels you in again, and has you marvelling with him at the grandchildren's handstands and cartwheels on the paddle board on the river, or at the cunning of the dingo pair who've taken out a young Buru (kangaroo) by gripping him by the ears and drowning him.

Pascoe's conversational style works best when he both lets it run and warns you he may just be getting a bit fanciful in the retelling, as when he describes a seal he first met on the Wallagaraugh in 2002:

Lyn Harwood. Liz Waring/Thames & Hudson

Pascoe's partner Lyn is credited as the book's secondary author via smaller text on the book's front cover. Sometimes Pascoe quotes from her journal entries, discrete and beautifully rendered observations of wildlife on her own nearby property. She is frequently referenced as a companion during his daily activities.

But as I was reading, I found myself wondering how else Lyn contributed to the book, and on what terms. While the book's imprint page confirms that the beautiful sketch of the spur-winged plover on page 47, for example, along with all the other uncredited images, are Lyn's work, it bothered me, given the long history of obscuring women's contributions to literature, art and science, that a reader has to go looking for this information. Why not provide this credit to Lyn in situ, right beneath the image?

Read more: How the Dark Emu debate limits representation of Aboriginal people in Australia

Connection to culture and CountryAt its heart, Black Duck: A Year at Yumburra, is Pascoe's slow and careful effort to assert and demonstrate his connection to Yuin culture, Gurandgi lore and Country on the basis of his daily, lived experience – and in the context of his accumulating knowledge of agriculture, history and spiritual relationships in the aftermath of Dark Emu and its attendant storms.

BlackDuck bookcover. Source: Thames and Hudson.

As if to underscore this, all four endorsements on the book's cover are from well-known First Nations Australians: Tony Armstrong, Allira Potter, Stephen Page, Narelda Jacobs. For anyone with lingering doubts about Pascoe's commitment and connection to Country, this book will set them straight.

The work has echoes of Tove Jansson's beautiful masterwork, The Summer Book , for its foregrounding of the land and its seasons, and for the emphasis on care and responsibility towards the natural environment. Pascoe's skill with the poetics of nature writing, imbued with Indigenous knowledge, does much to create the book's gentle pattern and its purpose.

It is a quiet, funny, warm and insistent call to return to and care for Country. In this way, Black Duck: A Year at Yumburra makes a welcome contribution to Australian nonfiction.

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the

information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept

any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images,

videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information

contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright

issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Comments

No comment