(MENAFN- Asia Times)

The Federal Reserve has unsettled world stock markets by signaling a blunder in monetary policy. Raising interest rates won't reduce inflation. If anything, raising interest rates will make inflation worse.

This isn't a conventional business cycle where excess credit leads to heightened demand for goods and services. It's a supply-side crisis. Interest rate policy is the wrong tool.

There's a simple way to stop inflation. The US government should stop its multi-trillion-dollar subsidy for personal consumption and instead support investment in productive capacity.

US manufacturing is shrinking, productivity is falling, and – as a consequence – unit labor costs to businesses are rising. There isn't enough supply to meet the demand that the federal government has unleashed.

The solution is a supply-side fiscal policy rather than a demand-stimulus fiscal policy.

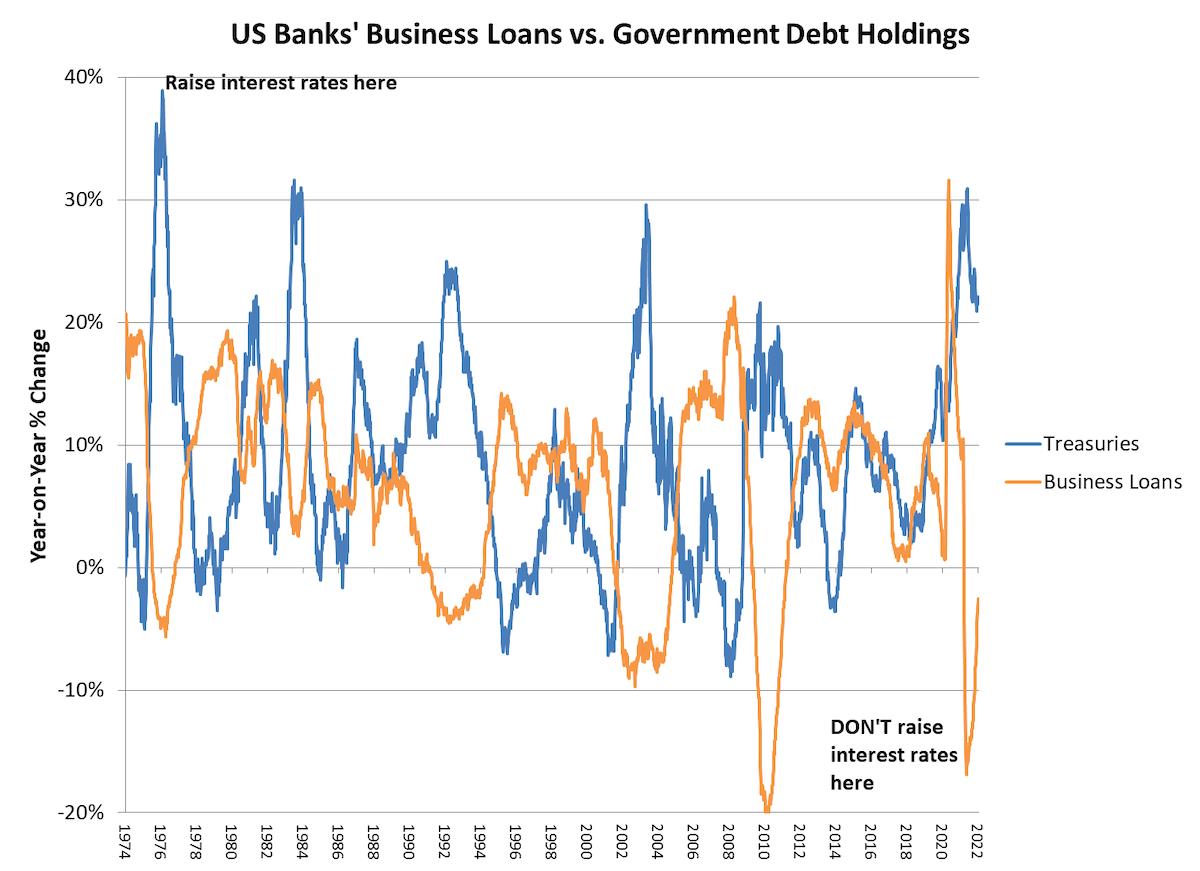

In 1978, at the peak of the last big US inflation, banks increased their commercial and industrial loan book at a 20% annual rate. Businesses loaded up on debt and bought real assets, expecting that real asset prices would rise and the real cost of debt service would fall.

That's what drives an inflationary cycle. The exact opposite is true today. American banks are shrinking their loan books at the fastest rate since the world financial crash of 2008-2009.

Consumer credit is also rising at a modest 5% annual rate. During the 1970s inflation, we observed several years of 15%-20% growth.

Excess credit issuance by banks is the whole rationale for hiking interest rates. When corporations and households expect more inflation and buy real assets with cheap credit, inflation expectations become self-fulfilling.

That's when monetary policy has a key role to play. The late Paul Volcker raised interest rates sharply in 1979 and began the long and painful process of suppressing inflation.

Volcker's tight monetary policy worked because the newly-elected Reagan administration adopted supply-side measures to promote growth, in the form of the Kemp-Roth Tax Cut of 1981, which reduced the top marginal personal income tax rate from a confiscatory 70% to 40%.

The late Robert Mundell, the Nobel Prize winner in economics whose theories inspired“supply-side economics,” argued that governments should apply the policy tool that most directly addresses the problem at hand – tight money to control inflation and tax incentives to boost output.

Today's problem is different. US manufacturing has been eviscerated by years of declining investment, as the consumer-oriented, entertainment-driven software sector gobbled up the nation's capital.

The result is shown in the chart below, comparing the growth in labor productivity (output per – of all US employees) versus unit labor costs. Note that productivity growth turned negative in the past year, while unit labor costs spiked to the highest growth rate in 20 years.

The circled areas on the chart show recession periods. The comparison between the last couple of years of economic weakness and previous recessions is instructive, and alarming.

During recessions, when participation in the labor force falls, productivity usually rises. The least-productive workers are let go and the remaining workers typically are more efficient.

During the past two years, though, productivity turned negative while unit labor cost growth surpassed 6% a year.

There are two main reasons for this perverse outcome.

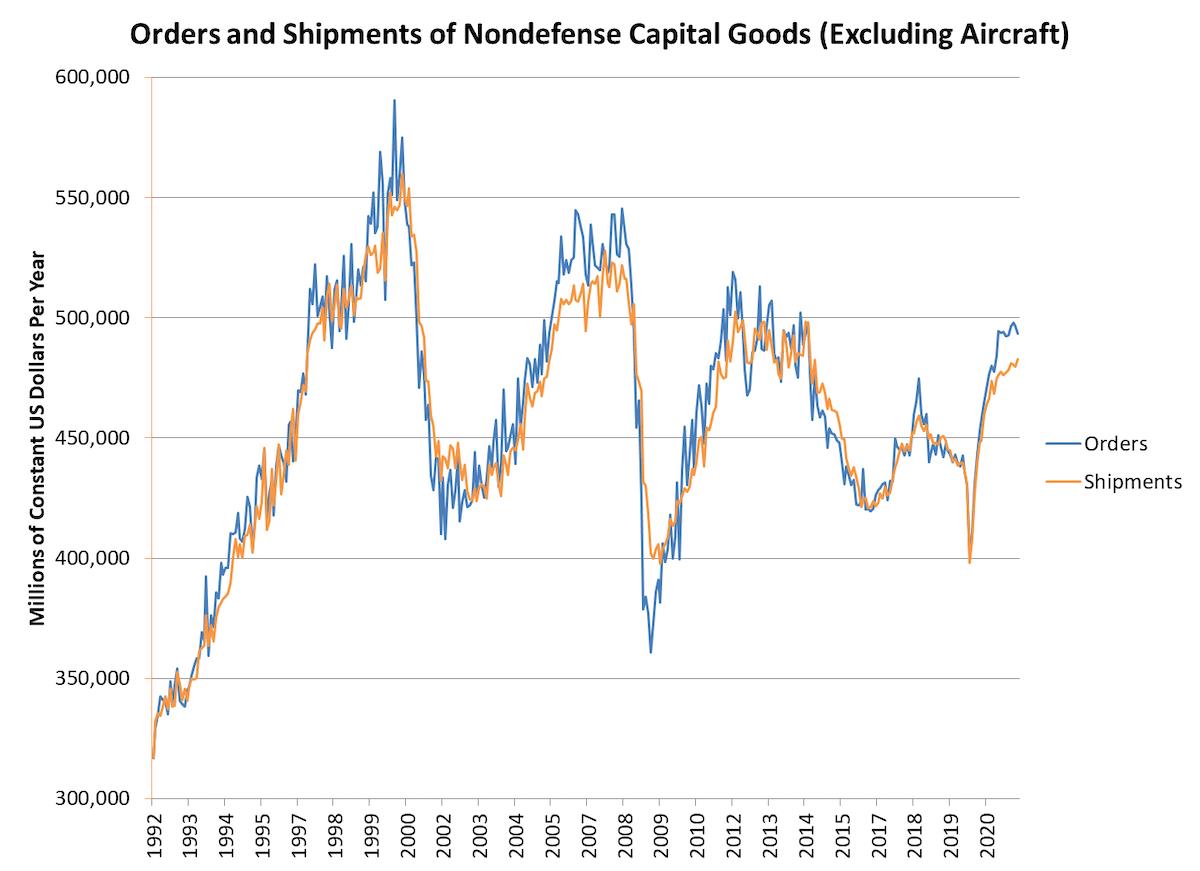

The first is chronic under-investment in plant and equipment. Deflated by the producer price index for private investment goods, orders and shipments of US non-defense capital goods show a bouncing ball pattern, in which each recovery falls short of the previous peak.

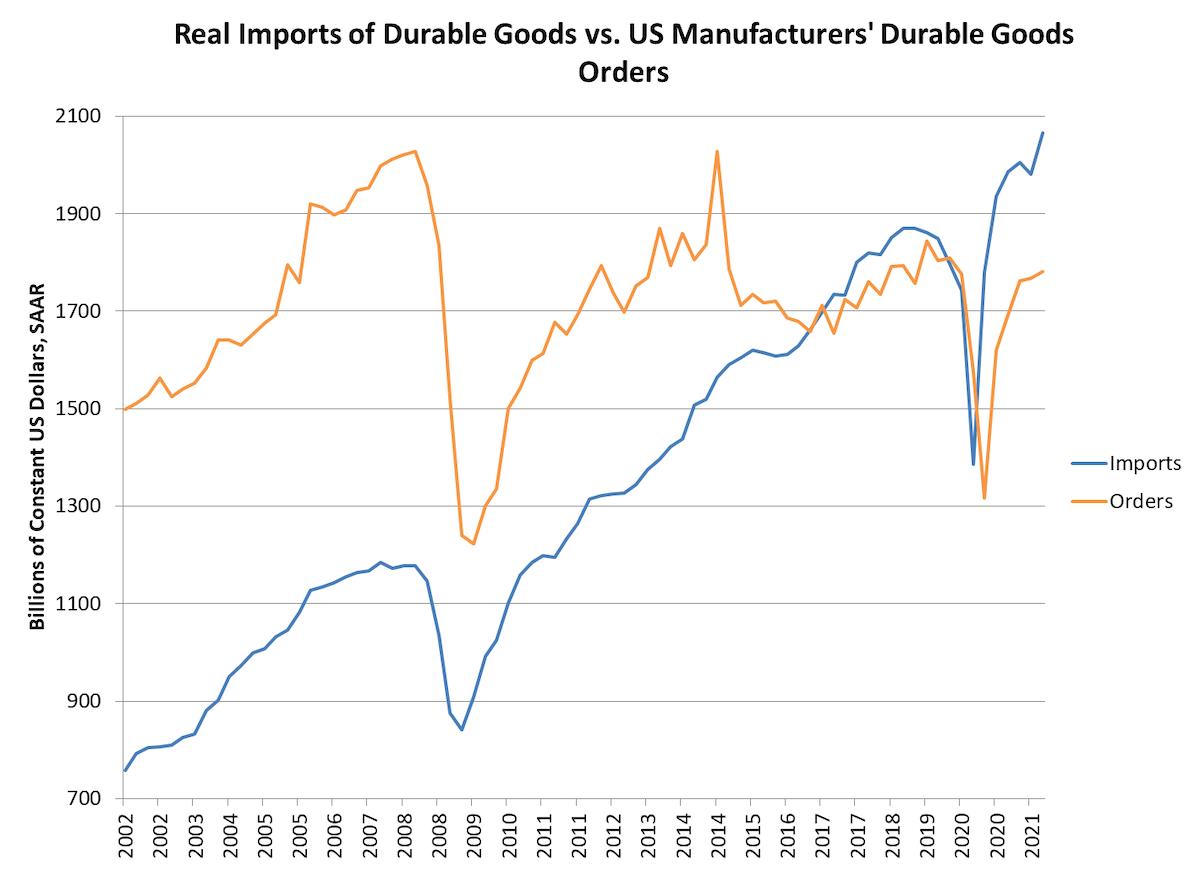

If the US doesn't invest in capital goods, it can't produce manufactured goods. In constant dollars, we see in the chart below, US imports of durable goods 20 years ago were only a third of orders for durable goods at American manufacturers.

Today imports are higher than total domestic orders for durable goods.

After taking inflation into account, orders at US factories for all durable goods, consumer items as well as capital equipment, are well below their level before the world financial crash of 2008.

Imports of durable goods, meanwhile, rose above the level of domestic orders. Remarkably, imports surpassed domestic orders for the first time during the Trump administration, despite tariffs on Chinese imports.

US supply chains are broken. The Trump tax cut, as noted by Rob Atkinson of the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, reduced the headline tax rate, but also removed tax breaks for capital investment. In response, US corporations spent more buying back their own stock than they spent on CapEx in 2018.

Restoring US manufacturing and technology leadership will be expensive and challenging (I offered a set of proposals in a December 2021 monograph for the Claremont Institute ). But increasing supply is the only way to stop the present inflation wave.

As noted, raising interest rates won't do anything to stop inflation. To the extent that higher rates do anything, they will increase inflation.

Higher mortgage rates will price more prospective buyers out of home ownership, forcing them into rentals. And rent inflation – running at a 14% year-on-year rate according to the Zillow Index – will be the biggest contributor to increases in the Consumer Price Index during 2022 (see Worst US inflation since 1982 is a huge underestimate , Asia Times, January 13, 2022).

Follow David P Goldman on Twitter at @davidpgoldman

MENAFN28012022000159011032ID1103604513

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images, videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.