Author:

Lee Raye

(MENAFN- The Conversation) The UK is one of the most nature-depleted countries on Earth, according to a recent assessment , and ranks among the bottom 10% for biodiversity globally. Some conservationists are hoping to change that by reintroducing species from the island's wilder past. One such candidate is the Eurasian lynx – a feline mammal.

As recently as 1974, experts like Anthony Dent, author of Lost Beasts of Britain , believed that lynxes belonged with cave lions in Britain's distant prehistoric past . But this theory was challenged by zoologist David Hetherington and colleagues in 2005, when they presented radiocarbon dating evidence that lynxes were around as late as the fifth or sixth century AD in north Yorkshire.

Although rare, lynxes persisted on isolated wooded mountains in Italy and elsewhere in western Europe as late as 1800. But until today, the most recent credible record of lynxes in Britain was a 16th-century letter from Polish author Bonarus of Balice to famous Swiss renaissance naturalist Conrad Gessner. The letter describes the best lynx skins as coming from Sweden, and, surprisingly, Scotland. In 2017 when writing about this source, I suggested that it most likely referred to lynx furs imported to Scotland and then re-exported. But new evidence has made me reconsider my opinion.

In a study published in the journal Mammal Communications, I present the most recent, and perhaps the most reliable British record yet. Richard Pococke's Tour of Scotland, published 260 years ago in the year 1760, seems to describe a population of lynxes breeding near Auchencairn, a village near Kirkcudbright in Dumfries and Galloway, southwest Scotland.

The missing lynx

I first discovered this reference while gathering data for my Atlas of Early Modern Wildlife, a book which will map records of wildlife made by naturalists, local historians and travel writers in Britain and Ireland before the industrial revolution.

While the last securely dated remains of lynx come from two centuries after the Roman withdrawal from Britain, the new record falls in the Georgian period, not long after the Jacobite rising of 1745. The author, Richard Pococke , was at that time Bishop of Ossory, and a Fellow of the Royal Society. He was a well-known travel writer and wrote detailed notes on the historical, architectural and natural points of interest in the places he visited. Pococke's record of what appears to be a breeding population of lynxes was one of these notes, made for the interest of his learned readers.

Pococke refers to 53 species over the course of Tours of Scotland. Many of these records, like the golden eagle, capercaillie (a large species of grouse) and mountain hare, are exciting for modern readers, but all bar the lynx are known to have been present in Scotland when Pococke visited.

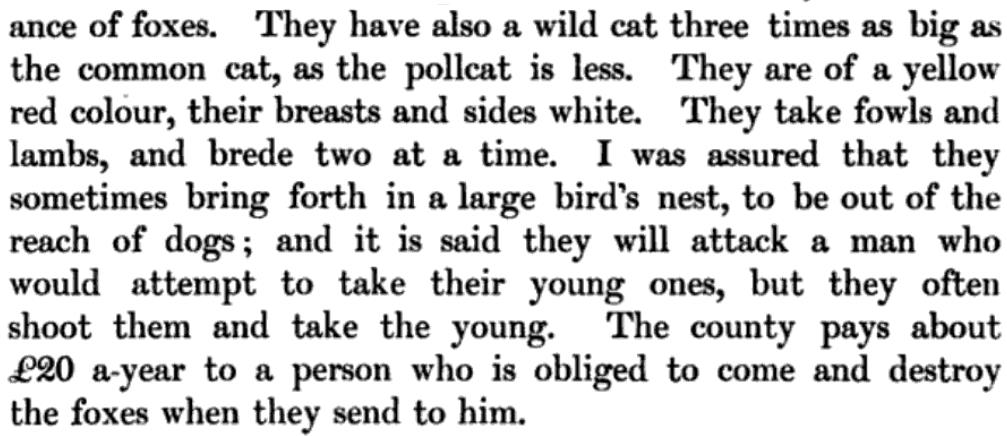

Historical records of wildlife can be difficult to use. Not only is it possible that the author misunderstood what they saw and heard, but their record might be exaggerated, and our understanding of the record might be wrong. This record is an especially tricky one to interpret. One of the reasons it has escaped the notice of historians is that it refers to the species involved as“a wild cat”. I suggest it is a lynx based on the description. Pococke describes a mammal three times as large as a“common cat” which was“yellow-red” with white breast and side and breeds in litters of two, in trees, and took poultry and lambs.

Excerpt from Richard Pococke's (1760) Tour of Scotland (Kemp ed. 1887). Kemp ed. 1887, Richard Pococke, Tours in Scotland 1747, 1750, 1760), Author provided This description fits a lynx better than it fits other species known to be in the area.

Fit the bill? A lynx at Camperdown Wildlife Centre, Dundee, Scotland. Martin Allen, Author provided Reintroducing lynxes today

This record is especially timely as the lynx is now being considered for reintroduction. The Lynx UK Trust has prepared a second application to reintroduce lynxes to Kielder Forest in northeast England and a project called Lynx to Scotland has launched a consultation about reintroducing lynxes there.

Returning lynxes to the wild in Britain is controversial because, unlike the osprey, sea eagle and red kite, the lynx was thought to have gone extinct much earlier. Critics of the reintroduction say that the landscape of Britain has changed too much for lynxes to fit in. But if Pococke's record is reliable, the lynx may have survived in Scotland much later than previously thought, and in conditions which are more similar to today.

For comparison, Scottish beavers were hunted to extinction in the 16th or 17th century while the last breeding cranes were recorded in 1603 . Both species have now reestablished breeding populations.

Supporters of lynx reintroduction sometimes suggest it wouldn't affect industries in Scotland. But the lynx in Pococke's 18th-century record was disruptive, taking lambs, poultry and grouse and enraging landowners who hired hunters to control the animals.

The lynx's diet might have been a response to human activity. In 1760, the red deer and roe deer seem to have been extinct as wild species in Dumfries and Galloway. The mountain hare was also gone, the brown hare had not yet been introduced, and the rabbit was mainly a coastal species. Although the inaccessible mountain terrain offered some sanctuary to wildlife, woodland coverage is likely to have been below 10% . These conditions are not suitable for the woodland-specialist lynx, which needs cover to ambush its prey, and likely contributed to the species' extinction.

Lynxes reintroduced today would have double the woodland coverage and plenty of natural prey, including rabbits, European hares and roe deer, giving them less reason to leave woodland and stalk sheep pasture, poultry farms or grouse moors. Compared with the situation encountered by the lonely and persecuted lynx of Pococke's day, 21st-century Scotland seems far more hospitable.

MENAFN11102021000199003603ID1102952403

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images, videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.