(MENAFN- Asia Times) TOKYO – China is so keen to maintain control over its sprawling and expanding economy that it's even willing to go communist.

For all the claims from Communist Party bigwigs that President Xi Jinping isn't on an anti-wealth crusade, the losses are too jarring to dismiss as“capitalism doing its thing.”

Indeed, the more than US$1 trillion of market capitalization losses tied directly to Xi's recent policies has China bulls mutating into China bears.

First, it was Jack Ma's Ant Group getting stomped by Xi's regulators. Then Didi Global and the $100 billion private tutoring sector got the boot. Next up is Tencent Holdings, China's top social media and video game platform.

On Tuesday, state media derided online gaming as “spiritual opium ,” clearly riffing off a famous Mao Zedong-ism.

That appears to answer investors' questions about whether Xi's crackdown on tech and tutoring companies will stop there. The emerging question is how much the blunt-force trauma inflicted by Xi's regulators will cost China's wider economy?

Jack Ma's outspoken honesty in deriding Chinese regulators invoked a severe backlash that has left his future unclear. Photo: Handout

A bridge too far?

Economist Scott Kennedy at the Center for Strategic and International Studies speaks for many when he worries that Beijing is going“too far” in ways that will damage growth in the short run and innovation in the long run.

In theory, Kennedy says, there's merit to policing monopolies and any abuses of power by tech billionaires when it comes to hoarding market share and user data. But the speed and seeming indiscriminateness of the clampdowns have“basically scared innovators from innovating,” Kennedy warns.

Longtime China booster Stephen Roach worries about a negative wealth effect that reduces top-line gross domestic product (GDP) growth in 2022 and beyond.

Eight months ago, says the former Morgan Stanley Asia bigwig, Xi's team seemed to have a“one-off, personnel problem” when they pulled Ma's $37 billion initial public offering (IPO). Ma's public rebuke about out-of-touch regulators and what he called a“pawnshop” mentality among state-owned banks crossed the line for Xi's party.

Ma has barely been heard from since.

The pivot to Didi Global last month, and subsequent chaos of the June 30 IPO in New York, showed Ma was not an aberration but instead the starting gun. First, China's answer to Uber disappeared from app stores. Now, there's chatter about Didi being de-listed and fines exceeding those on Ma's Alibaba Group.

Yet there are fears that wider economic problems could be even more extreme.

People walking past the Tencent headquarters in the southern Chinese city of Shenzhen, in Guangdong province, May 26, 2021. Photo: AFP / Noel Celis

It would be bad enough, Roach says, if the“assault on tech companies were the only example of moves that restrain the private economy.” However,“Chinese consumers are also suffering,” he notes.

Aside from Covid-19 fallout – and signs that China's Sinovac vaccine isn't up to the Delta variant challenge – rapid population aging and weak social safety nets for health care and retirement income risk turning mainlanders into Japanese-style savers-not-spenders sooner than feared.

Put it all together, Roach says, and you have this: Expect less and less discretionary spending on everything from motor vehicles to appliances to furniture to travel to entertainment and other sectors that were expected to flourish as China zoomed toward high-middle-income status.

What worries economists like Roach is that household consumption is still less than 40% of GDP, the lowest contribution of any major economy.

“The reason,” Roach says,“is that China has yet to create a culture of confidence in which its vast population is ready for a transformative shift in saving and consumption patterns. Only when households feel more secure about an uncertain future will they broaden their horizons and embrace aspirations of more expansive lifestyles.

“It will take nothing less than that for a consumer-led rebalancing of China's economy finally to succeed.”

Getting there, though, requires not only business and consumer confidence but private sector disrupters like Ma and Didi founder Cheng Wei , who push the economy upmarket and create millions of good-paying jobs and wealth.

Cheng Wei, chairman and CEO of Didi. Photo: AFP / Liang Zhen / Imaginechina

Beijing versus the innovators

Yet the fear and paranoia surrounding Xi's regulatory chaos sends a message – those wannabe innovators should consider a move to Silicon Valley, or perhaps change their focus and study finance.

Adding to the confusion about Xi's antitrust drive, says independent economist Andy Xie, is that monopolies like Alibaba became that way through government support. Not necessarily financial support, granted, but Beijing cleared the way for a handful of internet giants to build enough scale to make waves around the globe.

The eccentricities of tech founders, who served as the face of China at Davos, were long tolerated and even celebrated. That is, until they became too big and arguably too influential.

“The government,” Xie – who is also a Morgan Stanley alum – says,“may have come to view them as threats to its rule.”

That, notes analyst Jacob Gunter at the Berlin-based Mercator Institute for China Studies, means investors are in a place many hadn't anticipated. They are contending with party leaders who“seem increasingly comfortable with accepting considerable economic damage in order to achieve non-economic goals.”

Posterity might not ever know for sure whether Ma's infamous October 24 speech in Shanghai was a catalyst for the tech crackdown or an excuse to do what Xi's regulators had planned for a while.

In retrospect, Xi may have tipped his hat on imminent moves against tutoring companies in mid-June. Meeting with elementary students in the remote city of Xining then, Xi said:“We must not have out-of-school tutors doing things in place of teachers. Now, the education departments are rectifying this.”

Days later: Boom!

Certainly, just as with the regulatory crackdown on Ant, Didi and others, there are valid concerns at play. The data arms race warping American life, politics and economic incentives at the hands of Facebook, Google and other behemoths warrants regulatory responses in the biggest economy, too.

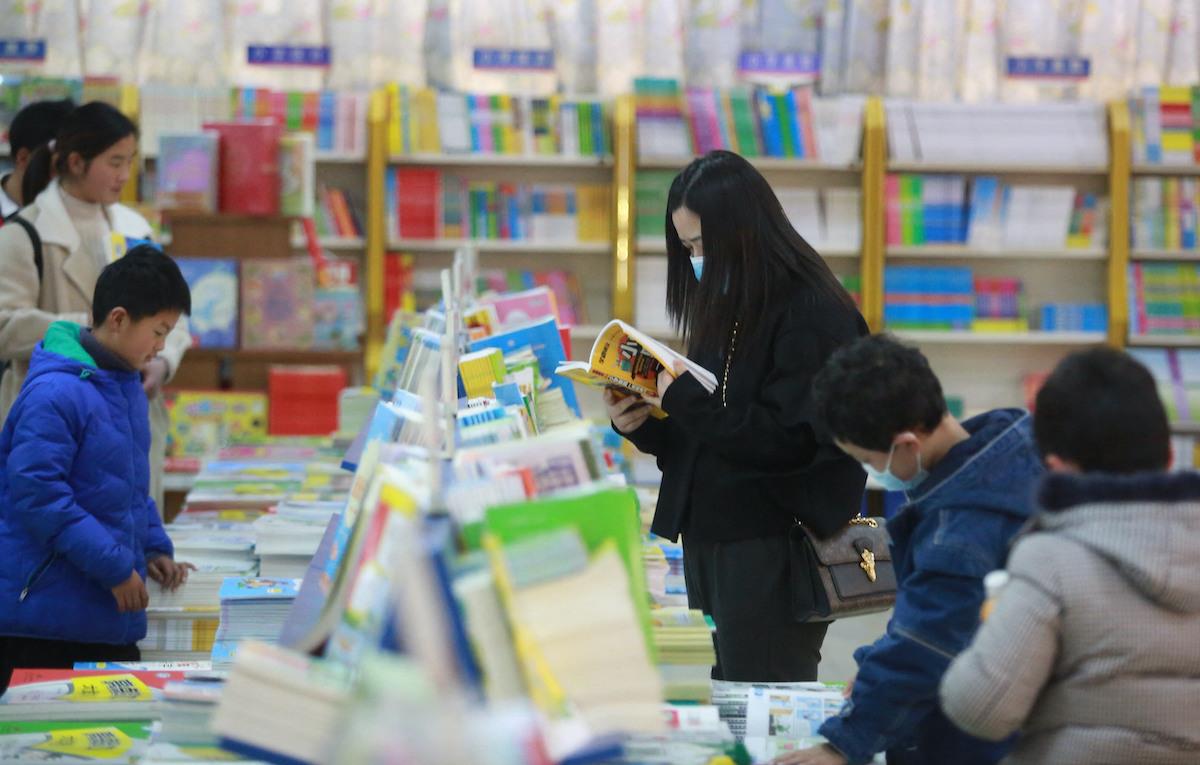

And as economist Xie points out, the cram-school craze is turning into an Olympic event of sorts for families to pay for extortionate tutoring services to secure places for kids in select kindergartens and primary schools. The prohibitive costs eat up discretionary spending and could dissuade families from having more children – a trend that has been noted in education-crazy South Korea.

In both cases, the problem isn't what Xi's regulators are doing, but how.

Many students shopped at a Xinhua Bookstore to choose after-school tutoring books to prepare for the new semester at the end of the winter vacation in Yangzhou City in east China's Jiangsu Province on February 20, 2021. Photo: AFP / Qianlong / Imaginechina

Sledgehammer tactics

A capitalist system of the kind Xi claims to favor would use tax incentives and regulatory curbs to influence behavior – not hit entire sectors with a giant sledgehammer, with little regard for how the impact might play out in investment bank boardrooms from New York to Frankfurt to Tokyo.

Late last month, China's top regulators reportedly reached out to some of the biggest names in global finance – including Goldman Sachs and UBS Group – to calm nerves among market players. Reportedly Fang Xinghai, vice-chairman of the China Securities Regulatory Commission, was among those leading discussions.

The message was Beijing will take market impacts into consideration before taking additional regulatory actions.

Fang, according to press accounts, assured the titans of global finance that Xi's priority was to ensure industries from fintech to private tutoring evolve in a productive manner. And that China's objective is not to decouple from the US economy or global markets.

Yet that reassurance may not be enough. After all, China's political turn since early November 2020, when Ma's Ant Group planned history's biggest IPO, has been nothing less than“tectonic,” says economist Richard Yetsenga at ANZ Banking Group.

And the economic risks are still unclear. If innovation and new startups don't materialize to support the rapid growth Xi's party needs,“the focus will once again be on manufacturing and consumption,” Yetsenga says.

That's easier said than done should global growth underperform over the next few years. As the Delta variant upends recovery hopes in the US, Europe, Japan and beyond, China's export engine may have difficulty finding growth sources.

China experts are, of course, doing their best to rationalize what Xi might be up to. One possibility of many, says Louis Gave of Gavekal Research, could be a reaction to the anti-China policies that have been pouring forth from the White House since 2016.

Xi's recent decisions, Gave says, may be“driven by a geopolitical assessment of China's situation .”

In essence, he says,“the Chinese leadership has concluded that the US is now gunning for China and that China needs to build a war-ready economy – by accumulating large strategic reserves of energy, building a domestic semiconductor industry and so on.”

One could argue, Gave says, that“it is the job of any leader to hope for the best and plan for the worst. And if you are Xi, planning for the worst likely means insulating China as much as possible from the US. In this sense, capital markets may not be a bad place to start in order to convey your message to the country.”

The bottom line, Gave concludes,“there are numerous possible rational reasons for the Communist Party's course of action. There is no need to conclude Xi has gone mad and that there are no checks and balances to hold him back.

“As a result, what matters is what these actions will mean for China's future. The obvious answers are (i) less reliance on foreign capital, (ii) ever more industrial policy and (iii) continued social pressure to act for the greater good.”

Still, the economic side effects of such a policy could be extreme.

A Chinese investor walks past a screen displaying stocks rising – red is up and green is down – across the board in Shanghai. Photo: AFP

Farewell, foreign capital?

A major Xi success has been internationalizing the yuan and opening capital markets to foreign investors. Since 2018, Shanghai shares have been added to the MSCI index and Beijing's debt included in top bond benchmarks – including the FTSE-Russell.

The scattershot approach Xi is taking in hitting some of China Inc's most vibrant sectors could turn off many of the investment giants Xi hoped to court. If investors lose trust in Xiconomics, forthcoming IPOs and China's $18 trillion government bond sales could find fewer buyers.

The first real crisis of the Xi era was in the summer of 2015, when Shanghai went into freefall. Shanghai shares fell 30% in a few weeks, a plunge that began exacting huge losses on bourses from New York to London to Hong Kong. Economists everywhere worried the Chinese debt crisis might follow.

Xi's government moved aggressively to stabilize the market – and succeeded. All was forgotten within a year.

Now, rather than saving the day, Xi's policy surprises are generating near panic in certain circles, mass confusion and sizable losses. The way out, most investors argue, is more Adam Smith and John Maynard Keynes, less Mao – or more“animal spirits” than“spiritual opium.”

As Tencent seems sure to learn in short order, investors should brace for more pain to come.

MENAFN03082021000159011032ID1102560364