(MENAFN- The Conversation) About a century ago, a poor country in northern Europe made a big leap into modernity. Using new technology, engineers to harness the energy in Sweden's roaring rivers, generating electricity which would, for the first time, find practical use in homes, factories, railways and agriculture.

Taking place decades after Sweden's nineteenth-century mechanisation, this electrification was the country's . It brought with it powerful forces of change that swept through civilian life, stoking tensions between employers and workers as evidenced by a huge increase in strike action at the time.

But here's where the narrative takes a surprising turn. Unlike the famous machine-breaking of Britain's first industrial revolution, Sweden's protesting workers didn''t seem anxious or angry about the technological change taking place in their factories. Instead of fearing for their jobs, found that the vast majority of Sweden's strikers were simply demanding higher wages.

Today, we''re living through a , marked by advances in computing power and breakthroughs in artificial intelligence. It has provoked its own backlash – some call it a '' '' – and has caused some workers to fear that .

Read more:

Sweden's workers expressed no such sentiment during the country's electrification, suggesting that can empower workers rather than leaving them feeling vulnerable or exploited – a lesson we could apply to today's innovations and the anxieties that have accompanied them.

Technological revolution

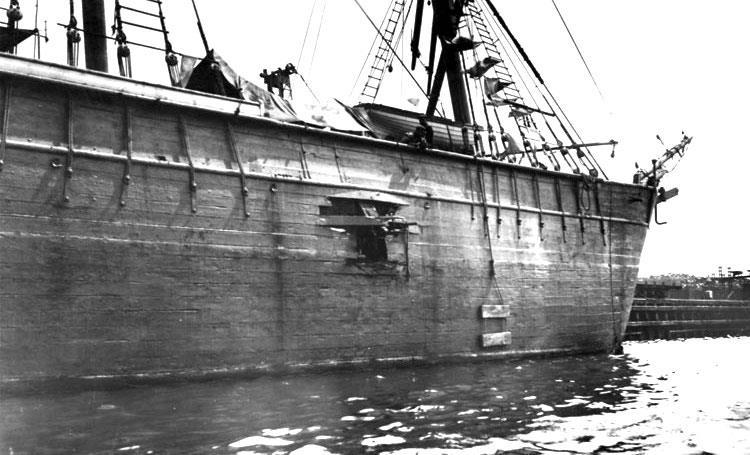

For some decades around the turn of the 20th century, Sweden experienced a period of upheaval. Workers had begun to form unions and perform strikes. Strike action became increasingly audacious, leading to the on a ship named Amalthea in 1908, which had carried British strikebreakers to the docks of Malmö. The explosion killed one and wounded 23.

The hole blown in the side of the ship Amalthea. The episode is regarded as Sweden's first terror attack. , A year later, organised labour and capital met in a of strikes and lockouts. Employers would eventually . But protests continued through the , with ordinary men and women taking to the streets to protest soaring food prices. , forcing politicians to finally take moves to extend voting rights for working-class people.

This was a formative phase for Sweden's institutions and the between citizens and the state. It also happens to have been a time when Sweden was busily building a national grid, powering homes and factories with electricity generated by its new hydropower plants.

For workers, this meant change. Electricity enabled owners to do away with the single that drove machines via a series of belts, using instead a number of smaller motors for each machine. This provided firms with a more reliable source of energy, increasing the pace and continuity of production. This in turn made some jobs obsolete – though it also created new ones.

It's tempting to assume that these forces – technological change and labour conflicts - were related. The narrative close to hand is that workers went on strike to block the new technology and to save their jobs.

We know that was often the case in Britain during the first industrial revolution, when some workers torched their own mills and . During the Napoleonic Wars, the secret continued in the same spirit and later, in the 1830s, agricultural workers protested the introduction of threshing machines in the so-called .

Read more:

Swedish workers protesting wage reductions in 1931, after the country's electrification. , For our research, we searched the records of over 8,000 work stoppages recorded by Swedish authorities between . Among these events, we were surprised not to find a single strike with the declared purpose of protesting electrification, and just a handful of strikes that were described as attempts to reverse mechanisation more generally.

To see if there were more subtle links between technology and labour conflict, we then conducted a , consulting maps of the early electricity grid and comparing them against census data on Sweden's parishes at the time.

Before electrification, the parishes didn''t differ all that much. But as the grid materialised, those parishes that were supplied electricity suddenly experienced radical changes, including a sharp increase in strikes. So while workers didn''t directly relate their strike action to electrification, our findings suggest the two were indeed linked.

Fourth industrial revolution

We know that the strikes increased among Sweden's industrial workers, whose skills were in high demand, but not for agricultural workers, whose jobs were disappearing. We see the same kind of pattern today: high-demand Google workers have and , but workers in declining industries have lost their bargaining power and their collective voice.

But unlike Sweden's experience of electrification, today's industrial revolution features a strong , with some researchers predicting that in the US could be at risk of technological replacement. This fear has only been by the economic uncertainty caused by the pandemic.

We can understand today's automation anxiety with reference to our study of Swedish workers. Technological revolutions often produce , but we found no such response from the unions and strikers we researched. Instead, it's clear that new technologies can also empower workers – but only when they recognise that they ought to enjoy a share of the increased productivity delivered by technological change.

MENAFN17052021000199003603ID1102093246

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images, videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.