(MENAFN- The Conversation) The recent conviction of white Minneapolis police officer, Derek Chauvin, for the murder of a black man, George Floyd, was widely welcomed in the US and elsewhere. The US police force has long been seen as helping to maintain the country's racialised system of inequality. In the face of that, Chauvin's conviction appears to be, as President Joe Biden put it, for people of colour.

But the way police violence can work to uphold systems of power has deep roots in history that stretch much further than the US. My research on the role of such violence in previously colonised countries highlights how arguments made in the Chauvin case have long been used to defend oppressive policing. And this could help explain why the Black Lives Matter protests that followed Floyd's murder resonated in countries around the world.

Solidarity protests against police brutality occurred in places including , , , , and – all ex-British colonies. They also experienced calls to ''decolonise'' policing, to reform policing systems by limiting their use of force, reducing their ability to victimise poor, racial, ethnic and religious minorities, and making police more accountable.

It may seem odd to think that police in various African countries, which are largely black, need to be decolonised. But these police forces often have their origins in colonial organisations that were not established to protect the public.

Their purpose was, instead, to serve as to protect colonial regimes from perceived threats by their colonised subjects. Since post-colonial states largely retained the systems of colonial policing they inherited, many police forces continue to uphold state power by enacting extra-legal violence against the poor and other traditionally marginalised groups.

My recent book, , details how in India the British relied on police violence, such as torture and other forms of brutality, to maintain an oppressive system of rule. In making the police '' '', as the 1902 Indian Police Commission put it, they thus sent a clear message to Indians that the purpose of the police was to protect the colonial regime, not them.

Police violence today is often explained by authorities as the actions of a few ''bad apples'' – this was the defence made . This effectively upholds the systems that produce and protect violence in policing.

Similar arguments were common under British colonial rule. White police officers in India were occasionally punished for the use of extra-legal violence. But they were generally, at worst, simply dismissed from service.

Imprisonment, on the rare occasions it was given, was largely reserved for colonised subordinates on the lowest rungs of the police hierarchy. This was despite the fact that such subordinates were , as the Indian newspaper the Ananda Bazar Patrika observed in 1913.

Victim blaming

In the Chauvin trial, the defence also portrayed George Floyd as being . In colonial contexts, (through which colonised peoples were blamed for the violence enacted by the colonisers against them) was similarly used to shift blame for extra-legal violence by colonial police forces against colonised victims.

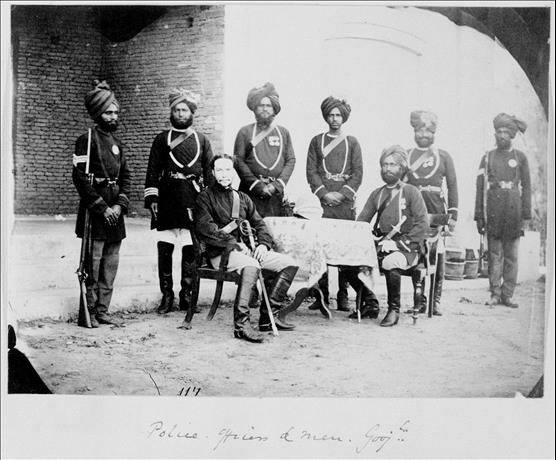

British Indian colonial police force pose for photograph in the city of Gujranwala, prior to partition, 1869. Such displacement ranged from blaming victims for bringing ''false charges'' to inflicting injuries on them that were so severe they could result in death. In 1866, for example, an Adivasi man (from one of India's indigenous ethnic groups) named Bheem was tortured so severely by members of the Indian police that he was unable to walk.

Although medical evidence supported Bheem's claim that he had been tortured, his torturers escaped conviction on the grounds that Bheem was a person of '' , namely that he was immoral and inherently untrustworthy. In addition, Bheem and his witnesses were sentenced to four years'' imprisonment for bringing false charges against the police.

In these ways, the history of colonial policing shows the scale of the challenge the world faces in tackling violent, oppressive and institutionally racist policing. Perhaps Derek Chauvin's conviction is a turning point for the US, but as , put it, people of colour will have to keep fighting against police violence ''for life''.

MENAFN12052021000199003603ID1102071456

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images, videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.