(MENAFN- Kashmir Observer) If you are a Pakistani man, here's why this Turkish woman has you simultaneously exasperated and enchanted

Aimun Faisal

IN the middle of a global pandemic, the state-run PTV began airing a Turkish historical fiction drama series, Ertugrul, which experienced such a meteoric rise in popularity in the country that it became part of the national discourse, causing several debates regarding the authenticity of our cultural histories.

Read that sentence again. Understand that it is true.

Imagine the events that must have aligned in a very precise fashion for it to have happened. And then realise this is not even what this piece is about because something even more fascinating - or absurd depending on how you view it - occurred.

The Pakistani male fantasy came to life. Playing the wife of the titular character on the show is Turkish actor Esra Bilgiç whose portrayal of Halime Hatun has led to a dedicated male following in our country.

It did not take long for her fans to look her up on Instagram, and then be promptly disappointed by the fact that she, in fact, did not dress or behave like the wife of a Muslim warrior from the thirteenth century.

Ever spurred on by their commitment to religiosity and piety, Muslim men from Pakistan who had looked up a Turkish actress on a photo and video sharing platform, felt it their spiritual duty to educate her, or advice her, or berate her - depending on their self-confidence - on the ethics of being a pious Muslim woman.

The catch here? It is very unlikely that she would have developed the massive male fan following that she had developed in such a short time in Pakistan if she did follow their code of conduct.

It is understandable if men would have felt slightly mystified, slightly horrified by this beautiful, Muslim woman who played by their rules on TV but "broke" them on social media yet continued to fascinate them more than she angered them. Something quite remarkable had taken place, after all.

For years, Pakistani men had successfully maintained a dichotomy between the foreign, white woman and the Muslim, brown woman. The foreign, white woman is an object of desire and lust, at once a woman to be feared, because of her colour, and a woman to be conquered, because of her sex.

The brown woman on the other hand, is supposed to embody the brown man's ideology. She is the keeper of the private sphere, and should submit entirely to the authority of the brown man.

You might be shaking your heads right now, negation on the tip of your tongue; I assure you I want to agree with you and believe that men do not, in fact, view women like this.

However, Frantz Fanon and Partha Chatterjee have written extensively about how the encounter of men of colour with colonialism impacted gender ties in the colony, and it seems that, unfortunately both our wishes remain unfulfilled.

The dichotomy however collapsed with Bilgiç who, at once possessed appearance close in proximity to European femininity, but the heritage and ideology of the brown, Muslim woman. She was almost white and Muslim enough. She was not to be feared, yet possessed all the desirability. And thus began the crisis that led to the barrage of comments on her Instagram posts.

For it had been easier with Pakistani actresses. These brown, Muslim women, who digressed, did not possess a local male following of such vigour and had to get used to their characters being questioned over the slightest digressions from expected behaviour. 'Is this the Islamic Republic of Pakistan?' has almost ascended to idiomatic status on Pakistani twitter, regularly used to caption pictures where Pakistani actresses show even the slightest bit of skin or are seen in close proximity to male colleagues.

There is a very simple logic to this: good, pious women are not supposed to stray so far from the private sphere that they enter the showbiz industry.

It had been similarly easy with Hollywood actresses. It is an open secret that men enjoy displays of sensuality by these foreign, white women, in whose life choices they do not expect their ideologies to be reflected, and thus feel no emotional stake in their 'characters'.

The logic to this is equally simple: men can easily separate the flesh from the humanity here that they cannot empathise with, and are thus free to lust after these women.

With a Turkish actress, it gets complicated. They want this woman to be Muslim and they need this woman to remain desirable. If she agrees to the former and reigns in her European femininity, she becomes as familiar and as 'ordinary' as the brown woman; erasing the charm that makes her desirable. If she tries to do the latter and dials back her 'Muslim-ness', she becomes as unacquirable and as foreign as the White woman; losing the empathy that had evoked an emotional response.

She was the ultimate Pakistani, male fantasy. A miracle happened and she became real. Now Pakistani men do not know how to deal with the paradox of the dichotomy their misogyny had created.

And it is absolutely hilarious.

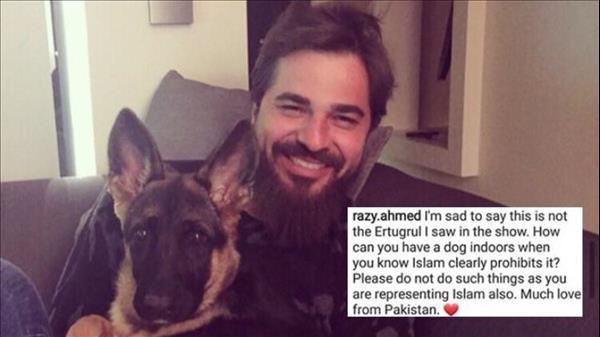

Of course, there was also the odd comment on the male lead's Instagram, warning him against keeping dogs as pets indoors, since that is against religious tradition in Pakistan. But neither the quantity or quality of the sentiment could compare to the emotionally charged moral bombardment in Bilgiç's comments section, that I can only hope she did not read.

There is, after all, a difference between your role model not acting in the way you want him to, and not knowing how you want your object of desire to act. So while Ertugrul has caused much debate about culture, and provided much entertainment amid a lockdown, it just feels a little unfair to not pay attention to the cultural development and entertainment value it has provided off-screen.

If you are a Pakistani man, spare a thought as to why this Turkish woman has you simultaneously frustrated and enchanted. If you're a Pakistani woman who has shouldered the burden of this ungrateful, Pakistani man's piety, look at him grapple with his own misogyny.

- The article originally appeared in Dawn and is being republished with permission from the author

| Be Part of Quality Journalism |

| |

| Quality journalism takes a lot of time, money and hard work to produce and despite all the hardships we still do it. Our reporters and editors are working overtime in Kashmir and beyond to cover what you care about, break big stories, and expose injustices that can change lives. Today more people are reading Kashmir Observer than ever, but only a handful are paying while advertising revenues are falling fast. |

| ACT NOW |

| MONTHLY | Rs 100 |

|

| | | |

| YEARLY | Rs 1000 |

|

| | | |

| LIFETIME | Rs 10000 |

|

| | | |

MENAFN0509202002150000ID1100752965

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images, videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.