(MENAFN- The Conversation) St. Peter's Fields in Manchester: theyear is 1819 , and a crowd of around 60,000 peaceful pro-democracy and antipoverty protesters have gathered to hear radical speakerHenry Huntcall for parliamentary reform. What should have been a peaceful appeal, ends with an estimated18 dead and hundreds injured .

This was a time in Britain's history when most people didn't have the vote and many regarded the parliamentary system – which was based onproperty ownership and heavily weighted towards the south of England– as unrepresentative and unfair. Factory workers had very few rights and most of them worked in appalling conditions.

As Hunt began his speech,the order was givenfor him to be arrested. After he had given himself up and again urged the crowd to order, the volunteer Manchester Yeomanry Cavalry attacked the platform, the flags, and those around with sabres, while special constables weighed in with truncheons. A charge into the panicking crowd by the 15th Hussars completed the rout.

As well as an attack on the working classes, Peterloo was also an episode of violence against women. According to thehistorian Michael Bush , women formed perhaps one in eight of the crowd, but more than a quarter of those injured. They were not only twice as likely as men to be injured, but also more likely to be injured by truncheons and sabres.

This was no accident, for female reformers formed part of the guard for the flags and banners on the platform, which were attacked and seized by the Manchester Yeomanry cavalry as soon as Henry Hunt had been arrested. But how did the women come to be in such an exposed position and why were they attacked without quarter?

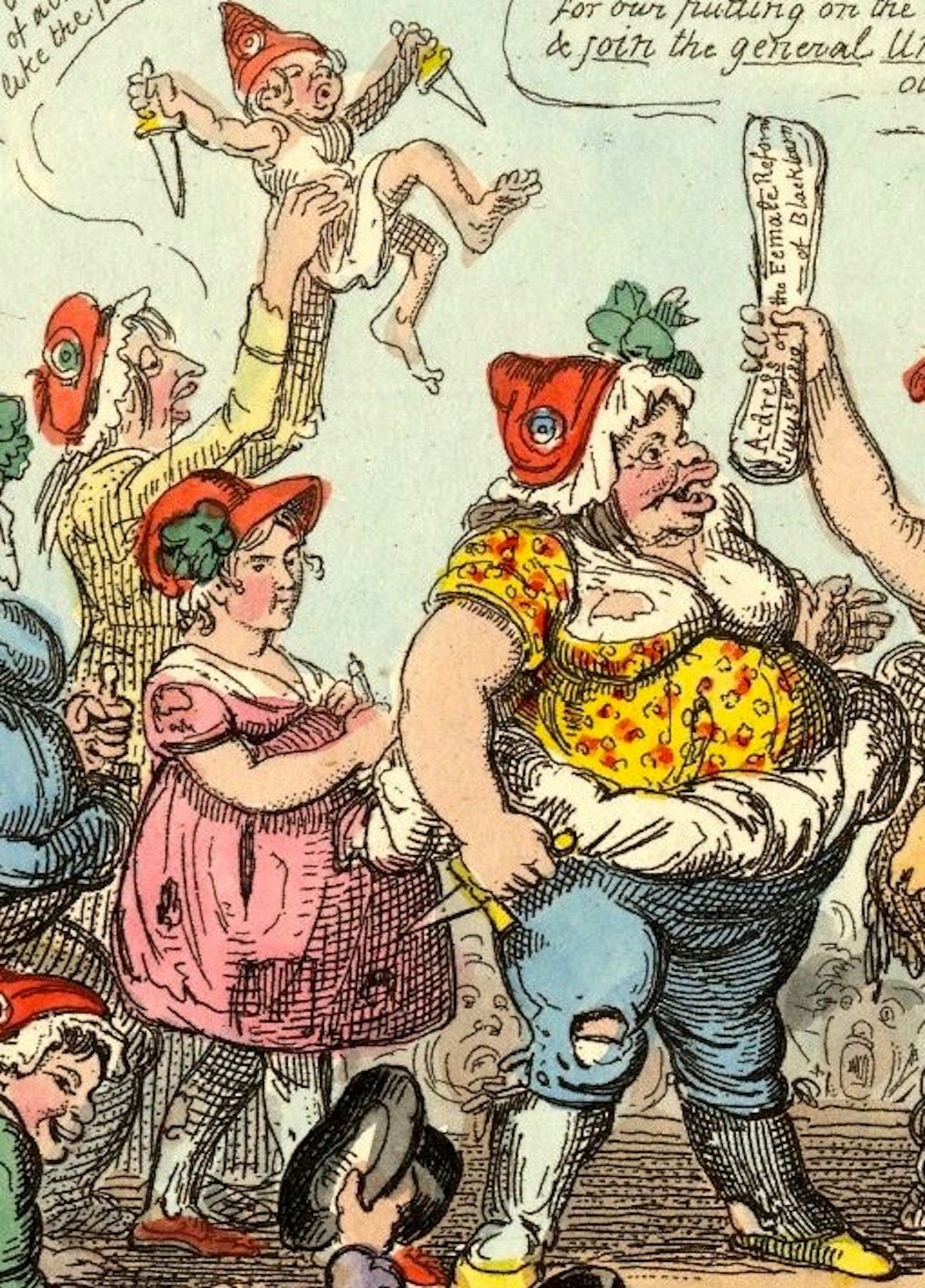

The hostile'Belle Alliance' cartoon of female reformers (July 1819) by George Cruikshank.

British Museum ,CC BY-NC-SA

The female reform societiesof Lancashire were a novelty, formed in the summer of 1819 in the weeks before the great Manchester meeting of August 16. They were not asking for votes for women, but they were claiming the vote for families, and a say in how that vote was cast. In an address which was to have been presented on the platform at Peterloo, The Manchester Female Reformers declared that 'as wives, mothers, daughters, in their social, domestic, moral capacities, they come forward in support of the sacred cause of liberty'.

They were there supporting their husbands, fathers and sons in the struggle for a radical reform of parliament. They took care to be feminine, but not what we would call feminists, yet they stretched the boundaries of femininity to breaking point and, in the eyes of government loyalists, renounced their right to special treatment.

More provocative still, parties of female reformers on reforming platforms presented flags and caps of liberty to the male reform leaders. The cap of liberty had been the symbol of revolution in France, but on the Manchester Reformers' flag it was carried by the figure of Britannia, as shown on English coinage until the 1790s.

This ceremony took the patriotic ritual of women presenting colours to military regiments and adapted it to radical ends. The Manchester Female Reformers planned to proclaim:

At previous meetings, the authorities had been unable to capture the radical colours and had suffered some humiliating rebuffs. The volunteer Yeomanry at Manchester were determined to reverse these defeats. When he heard the women would be on the platform again at Manchester, the Bolton magistrate and spymaster Colonel Fletcher wrote privately that such meetings 'ought to be suppressed, even though in such suppression, a vigour beyond the strict letter of the law may be used in so doing'. With Fletcher looking on, this was exactly what happened at Peterloo.

'Women beaten to the ground by truncheons'

Mary Fildes , president of the Manchester Female Reformers,is depicted in printswaving a radical flag from the front of the platform as the troops attack. She guarded her flag until the last minute, then jumped from the platform, catching her white dress on a nail and being cut by a sabre as she struggled to get free.

Cropped version of 'Britons strike home' (August 1819) by George Cruikshank.

British Museum ,CC BY-NC-SA

As she ran, she was beaten to the ground by a special constable who seized her embroidered handkerchief-flag, and then dodged another sabre blow and escaped into hiding for the next fortnight – although badly wounded she survived and continued to campaign for the vote.

Others were arrested in her stead and detained for days without trial in wretched conditions. One of them,Elizabeth Gaunt , suffered a miscarriage afterwards – her unborn child is listed as one of the victims of Peterloo onthe new memorial in Manchester .

George Cruikshank'sfamous graphic imagesof troops attacking defenceless women and children formed the enduring image of Peterloo in the public mind. After this propaganda disaster, next time round, in 1832, the government dared not risk sending in troops against unarmed crowds of reformers gathered in cities such as Birmingham, Manchester and Leeds. The House of Lords backed down at the third time of asking and theGreat Reform Actwas passed.

Behind Britain's famous long history of gradual reform lay the shock of Peterloo. And behind the granting of the franchise to more men lay the bravery of women.

History

Politics

Protest

India

Manchester

working class

Massacres

Empire

Vote

British Indians

Parliamentary reform

Peterloo

MENAFN1508201901990000ID1098886687

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images, videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.