(MENAFN- Morocco World News)  Isabella Wang

Isabella Wang

Rabat- Through the medium of photography, Moroccan artists have battled stereotypes and redefined what it means to be a Moroccan woman.

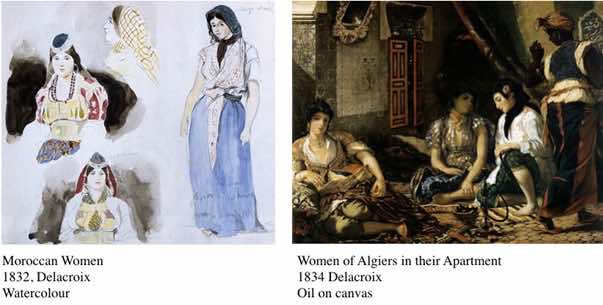

After the French conquest of Algeria, it was Delacroix who first ventured into North Africa and initiated the West's artistic fascination with the region. With bright costumes and the deep warmth of the dark, earthy colors, wonder permeates his artwork.

For in what was to him the unknown, he fantasized the orientalized myth of North Africa. Predicating his experiences upon the folk tales of Arabian nights, his paintings, including the iconic 'Women of Algiers,' conjured the lands of Algeria and Morocco as one of exoticism, adventure, and the harem fantasy.

Delacroix intended to reveal the lives of North African Muslim women behind the construct of their veil. Yet in so doing, he imposed upon them a sexualized and Westernized male gaze, whereby the languid poses and unbound clothing, alongside the tokenistic symbols of the hookah pipe and chambermaid, underpin an inaccurate oriental fantasy.

The distorted views propagated by Delacroix' artistry have remained constant within the Western collective conscience. It has become the very crux of the monolithic perceptions of Morocco which pervade the discourse on the nation and, more specifically, Moroccan women.

Only a month ago, Rihanna's makeup brand Fenty Beauty, which had been previously heralded for its diverse representation and inclusivity, played upon this orientalist myth.

After releasing a new palette called 'Moroccan Spice,' the subsequent espoused a tokenistic amalgamation of Arab fusion music, shawl costumes, and desert settings, including a camel.

Such imagery embodies the exoticized Maghreb region, a testament to how perceptions of Morocco are misrepresented and reduced to one-dimensional tropes of Arab women.

Writing in Al Araby, British-Iraqi journalist Ruqaya Izzidien said, 'The Moroccan Spice does nothing to acknowledge true Moroccan culture. Instead it cracks cheap puns that betrays Fenty's lack of understanding or research on North Africa while benefiting from the on-trend Arabian imagery that clearly lacks any input by Moroccans.'

The appropriative inaccuracies of Fenty Beauty's fetishized and orientalized depictions of Morocco only embody the underlying problems with cultural perceptions of the country and its population.

The new wave of photography

Yet to dispel the inaccuracies and stereotypes, Moroccan photographers have harnessed their artwork to redefine what it truly means to be a Moroccan woman. Photography is a medium predicated on a paradox: in the authentic depiction of the photograph is a reflection of reality, yet underlying the art is its innately constructed nature.

In the balance between reality and representation, Moroccan photographers Hassan Hajjaj and Lalla Essaydi have featured the subject of real Moroccan women and embedded a network of cultural symbolism to explore the uneasy tension between the visual and the symbolic; appearance and reality; and preconceived perceptions of Moroccan women and the complex, multi-faceted identities behind such perceptions.

Their artwork creates a dialogue with the audience, confronting them with authentic, nuanced portrayals of Moroccan individuals while imposing a critique on how previous artistic discourse has constructed and imposed a false cultural identity on Morocco.

Lalla Essaydi's art champions the Moroccan woman. She highlights the multi-faceted intricacies which have often been ignored or exoticized in the exploration of Moroccan female identity. Behind this diatribe is a deeply autobiographical quest. Her photographs stem from the need to assert her personal voice as she grapples with what it was like to grow up as a female in Morocco.

She stated, 'In my art, I wish to present myself through multiple lenses—as artist, as Moroccan, as traditionalist, as Liberal, as Muslim. In short, I invite viewers to resist stereotypes.'

Moroccan photographer and street-wear artist Hassan Hajjaj was similarly displeased with depictions of Morocco; on fashion shoots in Morocco, he perceived that the scenery of the nation was exploited as a flat exotic backdrop for European models. His work thus embraces a playfulness and urban trendiness which embodies the life of Morocco beyond the perceptions of the exoticized and antiquated.

He on the decision behind his artwork, 'I wanted to do something to present my own people who stand between the traditional and the modern. I wanted to represent my own friends.'

Embrace the veil

While Delacroix sought to 'unveil' the women of the Maghreb region and propagated the belief of the veil as a construct imposed upon women, Essaydi and Hajjaj now embrace it. They redress the stereotypes and perceptions attached to the veil as a commentary on modern female identity in Morocco.

Lalla Essaydi's photographic series 'Les Femmes du Maroc' (The Women of Morocco) revisits the contentious locus of the harem and unravels the byzantine layers of meaning attached to the space. Within the harem, her subjects of real Moroccan women reclining while donning the veil and even the depiction of a chambermaid mimic and directly retort the orientalist gaze of artists such as Delacroix.

As a Muslim woman who had grown up in a harem before moving to Saudi Arabia, France, and the United States, Essaydi has profound insight into the complexities of cross-cultural identity politics. Yet, Morocco and the harem have remained intrinsic to her identity.

She recalls in an interview with , 'My work is haunted by space, actual and metaphorical, remembered and constructed. My photographs grew out of the need I felt to document actual spaces, especially the space of my childhood.'

Hence, integral to Essaydi's photography is her exploration of the dichotomy between private and public space.

She , 'Arab women traditionally occupy a private space, but wherever a woman is, when a man enters that space, he establishes it as public. This separation of public and private is testament to the power of women's sexuality.'

The powerful gaze of each subject to the camera is powerful and confronting. It challenges the audience's preconceptions of Moroccan women, and emphasizes the voyeurism of the past Western gaze, which has disrupted and distorted the private space of Arab women.

For Essaydi, the veil becomes a corrective force against the disintegration of the public and private. Behind the veil, the woman retains her private space and dictates how she is viewed. She is both empowered and subversive.

Hassan Hajjaj's photographic presentation of the veil similarly evokes power. In his ongoing series 'Kesh Angels,' his photography is rebellious yet playful. Hajjaj depicts female bikers wearing the hijab to debunk the monolithic representations of the West and showcase a subculture, which embodies the exuberance and complexities of Moroccan women.

The women in the series pose, wink, kick, lift, and run, all with irreverence and cheek. Their hijabs are marked by bright prints and sportswear logos, such as the iconic Nike tick, emphasizing the commonality and ubiquity of their experiences. In the cheerful, familiar, and bold, Hajjaj pokes fun at the West's notion that Arab women are isolated and powerless.

In an interview with , Hajjaj commented, 'Firstly, the headscarf is not always religious. Now, in the west, it is always seen as such, but the origins of it are not solely Islamic. People are just reading into it and making their own assumptions of the work. For me, it is all very Moroccan with the bright colors and the strong patterns that play on busy textiles.'

Celebration of Moroccan culture

Yet, Moroccan female identity transcends the traditional symbols of the harem and the veil. To be a Moroccan woman is to embrace the vivacity and complexities of Moroccan culture itself.

Embedded within Essaydi's artwork is the rich interplay of traditional artistic practices, representative of Moroccan culture. With her use of calligraphy, textiles, zellige tiling, and henna also comes their reinvention. Artistic reinvention provides a platform to assert her own voice and, by extension, to represent the evolving nature of Moroccan female identity.

Essaydi fuses Kufic calligraphy with the application of henna to create a poetic script, which sprawls across her female subjects' bodies, clothing, and the spaces around them. The script features a stream of consciousness chronicle of the subjects' and her own experiences as women, forging a platform for their own stories. It is a subversive act, which feminizes and reclaims what Essaydi in Islamic culture is a traditional male domain of writing and calligraphy. Yet, the script is also deliberately indecipherable.

For Essaydi, calligraphy transcends mere representation. It is a performative act; drawing upon the Amazigh beliefs that henna is a purifying rite which infuses the body with healing energy, the very act of inscribing in henna emphasizes the perpetual, and collaborative processes of becoming and creating.

It is thus in the amalgamation of masculine art forms and feminine henna, writing and imagery in which Essaydi dissolves the contradictions she perceives within her culture, contradictions between fluidity and hierarchy and between the richness and confining aspects of Islamic traditions.

In an ode to the architectural masteries of Morocco, Essaydi incorporates the zellige technique from her setting, the harem quarters of the Dar al Basha palace in Marrakech, and transfers them to the very garments of her subject. In the mesmerizing and almost surreal melding of clothing and setting, Essaydi highlights that identity is inextricably linked to place.

In the past, the locus of the harem was one of isolation and concealment, yet also female solidarity. The changing dynamics of Moroccan households and, more generally, its culture, have made it possible for Essaydi to revel in its beauty and richness.

Morocco's status on women has evolved vastly from the days of the secluded harem. Underpinning the isolation of the harem was the , a personal status code based upon the Malikite school of Islamic law. It governed the status of Moroccan women in civil law, where women were treated as legal minors, deprived of the ability to deny marriage contracts and required to obey their husband in all matters.

In opposition to their lesser legal status, Moroccan women's rights activists called for reforms. Islamic feminist activists called for new readings of the Qur'anic texts and engaged in 'ijtihad' reasoning (the process of deriving the laws of the Shariah from its sources) to counter the effect of Islamic fundamentalism, which they perceived to be present in the code.

2003 was a momentous year for change. In October, King Mohammed VI a draft family law in Moroccan Parliament, consulting women's rights organizations during the process of drafting in order to assure the pertinence of the law.

In his address to the opening session of Morocco's parliament, the King asked, 'How can society achieve progress while women, who represent half the nation, see their rights violated and suffer as a result of injustice, violence and marginalization?

The final text of the Mudawana reform was promulgated in 2004, securing women's rights to self-guardianship, divorce, and child custody. A report from outlined that the law 'also placed new restrictions on polygamy, raised the legal age of marriage from 15 to 18, and made sexual harassment punishable by law.'

The law was considered by the UK's Overseas Development Institute ( ) as 'one of the most progressive in the Arab world.' It initiated women into Morocco's political and discourse, while embodying the evolving and renewed perspectives on women in Morocco.

Inspired by the memories of his childhood, Hajjaj celebrates the vivacity of Moroccan identity. He imbues his shoots with movement and life: the energetic freedom of his subjects and the addition of live musicians and dancers verge upon performance art, reflecting the constant bustle of the medinas (walled cities).

Compounded with this is the exuberance of color: the female subjects are dressed in jolts of color, posing against bright mats and geometric patterns which evoke the zellige of Moroccan architecture.

Further adding to the artistic mosaic, Hajjaj uses everyday household items from Moroccan corner grocers to frame his work. Ranging from Arabic Coca-Cola cans to butterfly matchbook and coconut milk containers, Hajjaj evocatively celebrates the life of the souk while also creating a Warhol-esque aesthetic. Playing upon the roots of pop art as a platform for irreverence and critique, Hajjaj humorously depicts the urbanism and consumer culture which is often overlooked in Western perceptions of Morocco.

Morocco has undoubtedly become globalized. Hajjaj serves to emphasize this fact in his work. The culmination of brands, ranging from Nike to Louis Vuitton, reflect the urban streetwear trends and the counterfeit culture which is integral to the shops of the Moroccan medinas.

In fact, Hajjaj had turned down a with Louis Vuitton after the fashion company dictated that he would have to cease using counterfeit materials and incorporate authentic couture.

In an interview with , he stated, 'If I am using the real thing, it becomes more of a fashion shoot. When I shoot it's about making the person look grand even if the whole setup costs $40.'

In the friction between counterfeit and couture, Hajjaj harkens back to his origins as a fashion photographer on the exoticized backdrop of Morocco. He now can assert his agency in critiquing the schism between the reality of Morocco and the West's fantasies of it.

He debunks the cultural appropriation of the traditional discourse and instead celebrates the multi-faceted, paradoxical, and clashing identities which embody Moroccan identity: the amalgamation of religious tradition with modern consumerism, the customary with the urban, haute couture with hip-hop street style.

In the symbiosis between past and present, feminine and masculine, Arab, African, Amazigh, and French, Essaydi and Hajjaj uncover the multitudinous and byzantine facets which make up Moroccan female identity.

MENAFN1208201801600000ID1097283911