Asian countries could learn from others' solutions to democratic deficits

Democratic deficit, gerrymandering, redrawing borders, and continuous debate about elections are constantly in the news, and not only in the US and the UK but in Asia too (think Hong Kong and Taiwan), with various solutions being floated.

Surprisingly, none suggests taking a close look at the unique, successful, more than century-old Swiss 'direct democracy' combined with that country's proportional-representation experiment (in many respects more than a century old) that solved these problems and others that countries around the world have been fighting about and struggling to find solutions – one of them being preventing the tit-for-tat of two major parties cutting up states in the US when they get to power, or flip-flopping between consolidations and dispersions of power.

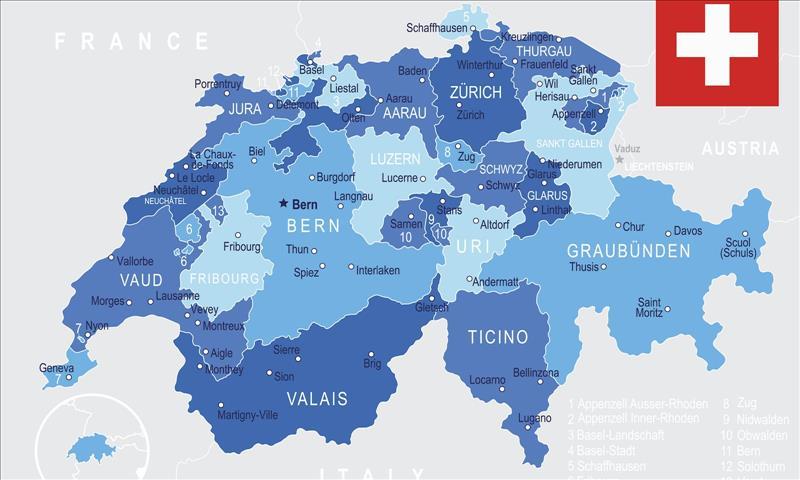

Must-reads from across Asia - directly to your inboxSince redrawing legislative districts and redrawing borders for secessions – or 'integrations' – have been much in the news – the constitutionality of the cases of Wisconsin and Maryland waiting for the Supreme Court to decide, and Scotland and Catalonia not quite settled, with perhaps Italy in the wings, with Taiwan noises regularly flaring up, never mind the continuous upheavals in the Middle East – consider how the Swiss solved political crises.

In 1890, intense mutual hatred of 'ultra-conservatives' and 'progressive radicals' and the winner-takes-all system brought the Italian-speaking canton of Ticino to the brink of rebellion. With 12,653 votes, the conservatives got 77 members in the ruling council, whereas the radicals, with 12,018, got 35, leading to an insurrection. The Swiss solved it by moving to proportional representation. That proved to be part of the solution for the Swiss, preventing cantons from splitting up – or even splitting from the Federation (Ticino was the last to join the reconstituted Swiss Federation in 1803).

In the US, solutions to abuse of power by the major parties gerrymandering to prevent more representative representation has been to delegate the decision to the courts or independent commissions, the argument being that these would make decisions on redistricting 'apolitical.' (Elsewhere people fought with swords, not words.)

This view does not hold up to closer scrutiny: Why would one assume that courts or independent commissions have a better idea how to improve the political process than the state electorate? One could – justly – argue that proportional representation does not solve the problem of interests of smaller constituents, and that appeal to the Supreme Court, whose principle in deciding on gerrymandering is presumably to sustain 'one man, one vote' can do the job.

First, the latter does not appear to be the case: Though the US Supreme Court has struck down cases it judged to be racially motivated, in other cases it did not disallow party-motivated gerrymandering. But, second, it is true that proportional representation alone is not a complete solution: Indeed, it was only part of what the Swiss did.

Combination is the keyThe Swiss realized that while proportional representation solves many problems – diminishing incentives for gerrymandering in particular – on its own it does not prevent democracies that practice it from lapsing into mazes of crises and corruption.

What the Swiss did is combine their proportional, representative democracy with the principles of 'direct democracy,' applying the latter to most major fiscal, regulatory, legal decisions at all levels of government, municipal, canton and federal. It is this combination that makes their political process unique and brought about greater accountability in governments at all levels than any other political experiments, and long-lasting stability and prosperity, and the most stable currency as well.

Citizens' right to call constitutional and legislative referenda, to challenge laws, taxes, regulations and governments' spending, has led to negotiations between parties, compromise and civil behavior – anchoring their country's stability and prosperity. Extreme propositions are curtailed, since majorities are expected to block them through initiatives, extremists then losing whatever small representations they might have had – which has been incentive enough not to be too extreme.

The combination of proportional representation and these features of direct democracy not only prevented incentives for gerrymandering, but drastically diminished 'personalities' getting into politics. Since politicians do not have much power under these combined political institutions, they know that anything they propose would be open to challenge through initiatives.

This brings about the relative unimportance of political platforms, ensures greater accountability and, not surprisingly, hearing more of minuscule Luxembourg's politicians than any Swiss one. Recall Oscar Wilde's play An Ideal Husband, where, when the size of the British government is limited, Lord Goring tells his father that only dull people go into the Parliament, and once there, only the duller ones can succeed.

A range of issues have been settled by the Swiss through the combination of proportional representation and 'direct democracy.' Over the past two years the Swiss approved an easier path to citizenship to third generation immigrants; approved creating a fund for infrastructure, but rejected overhauling part of the corporate tax code; and rejected raising women's retirement age to 65.

In 2016, the Swiss rejected the 'marriage penalty' in the tax code – but this appears to have been the result of having included in the same ballot a reference to marriage as a 'union between a man and a woman.'

Clarity crucialThis brings us back to the subject of gerrymandering and secession. In the 1995 referendum on separating Quebec from Canada, the question on the ballot was: 'Do you agree that Quebec should become sovereign, after having made a formal offer to Canada for a new economic and political partnership, within the scope of the bill respecting the future of Quebec and of the agreement signed on June 12, 1995?" The question was far from simple, mixing undefined 'formal offer' and undefined 'future political partnership' with a vote on sovereignty.

Ottawa quickly passed a 'Clarity Bill' that forced future referenda to have sharp, clear questions. It is surprising that after so many years of experience, the Swiss made the mistake of combining tax reform with a definition of personal partnerships.

Perhaps some Swiss watches are still perfect, but no political institutions are. Still, Switzerland's has gone further to solve the much-debated democratic deficits, accountability, Balkanization and redrawing of borders (bringing new cantons in, or carving up new ones with the Swiss Federation, such as the Jura) than any other tribe or tribe in the making.

The new institutions changed the Swiss, famous for exporting mercenaries for centuries, into the peaceable people they have become. Recall that a main Swiss export until the 19th century was mercenaries, fighting for Italy, Spain and France, among others. A remnant of this history can be still seen at the Vatican, where the Swiss Guard are present, the only exception permitted under the Swiss constitution of 1874 that outlawed foreign military practice. The timing was not surprising: By that time the Swiss had discovered how to transform snowy rocks into tourism and export them. In short, the Swiss were far from the calm folk they became after betting on a unique political combination.

What can countries around the world infer from this history, particularly Asian countries going through radical political experiments? That dispersing powers and sustaining accountability are the keys to solving 'democratic deficits' – in which light the recent re-concentration of powers by Chinese President Xi Jinping does not bode well.

Nobody really has any idea how exactly you move away from centralized and corrupt states lacking institutions to disperse power. Historical sequences of events make it clear, though, that centralizing powers and letting cash flow through politicians have been recipes for instability and disaster, changing people's behavior.

The Palestine experienceConsider the impact of the combination of electing Mahmoud Abbas in the West Bank – for supposedly four years in 2005 – and transferring money through him and his party with any notion of accountability. The consequences were predictable: corruption, political instability – and insurrection in Gaza.

The reactions were more extreme there, though if Western politicians transferring money through chiefs looked at the experience within their own borders, they could have predicted the trends. Consider all the ills plaguing aboriginal tribes in Canada: They came about with the misguided combination of their own 'gerrymandering' and transferring money through tribal chiefs, and legal constraints of people moving to reservations – moving to or quitting them. Such centralizing policies change people's behavior.

To conclude, it may take few generations for a country to become calmer and more civilized, but it may be doable. Not that I am particularly optimistic: Radical institutions happen only after a serious crisis.

The evidence from around the world about this is sharp and clear: Default or risking default and falling far behind have been the Mothers of Political Invention (though Stepmothers of Political Deceptions too – and with the world's population having grown from 1 billion to 7 billion in a century, with most political institutions unadjusted to this change – deceptions are more than likely for quite a while).

This article draws on Reuven Brenner's book Force of Finance, History – the Human Gamble.

Asia Times is not responsible for the opinions, facts or any media content presented by contributors. In case of abuse, .

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the

information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept

any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images,

videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information

contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright

issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Comments

No comment